This review appears in the new issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, N.29, on the theme of anarcha-feminisms. It is available from AK Press here!

Radicals, including many anarchists, are involved in actively organizing against gender and sexual violence around the world. For example, Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment/Assault in Egypt; Las Kallejeras in the shantytowns of Santiago, Chile; the Colectiva de Gafas Violetas in Mexico; and countless other local initiatives all confront perpetrators in workplaces and organizing work. Yet, the task of addressing sexual violence, even in anarchist circles, continues to be singled out as primarily the job of survivors and their most immediate circles, instead of as a collective political responsibility. As an issue that we are socialized to meet with silence and stigmatization, sexual violence is commonly underemphasized or obscured amongst both radicals and society at large. Take for instance, ignorance of the fact that one out of three women in the world will be raped at some point in their lives. Or that, in the US, ninety-one percent of reported rape survivors are women, the most vulnerable being queer and gender nonconforming youth and people with physical disabilities, and fifteen percent of children are survivors of rape and incest. It is critical that our politics be aware of and address this. We need to be more diligent and active in both understanding sexual violence and linking it to radical organizing.

Consider reading Dear Sister: Letters from Survivors of Sexual Violence (AK Press, 2014), an anthology containing fifty insightful pieces, written by survivors from all walks of life, as part of this process. The book features an introduction by African-American incest and rape survivor and filmmaker Aishah Shahidah Simmons, and is edited by Philipina-American feminist author and survivor advocate Lisa Factora-Borchers. Known for having extensive involvement with survivors via coalition work, nonprofits, and institutions of higher education before piecing together Dear Sister, Lisa Factora-Borchers was first approached by Black feminist author Alexis Pauline Gumbs who asked her to write a letter of support to a friend who had just been raped. Not knowing the survivor’s situation, her name, or much else about her, Lisa Factora-Borchers nevertheless acknowledge the situation and communicated support. Hence the idea for the book was born.

Perspectives

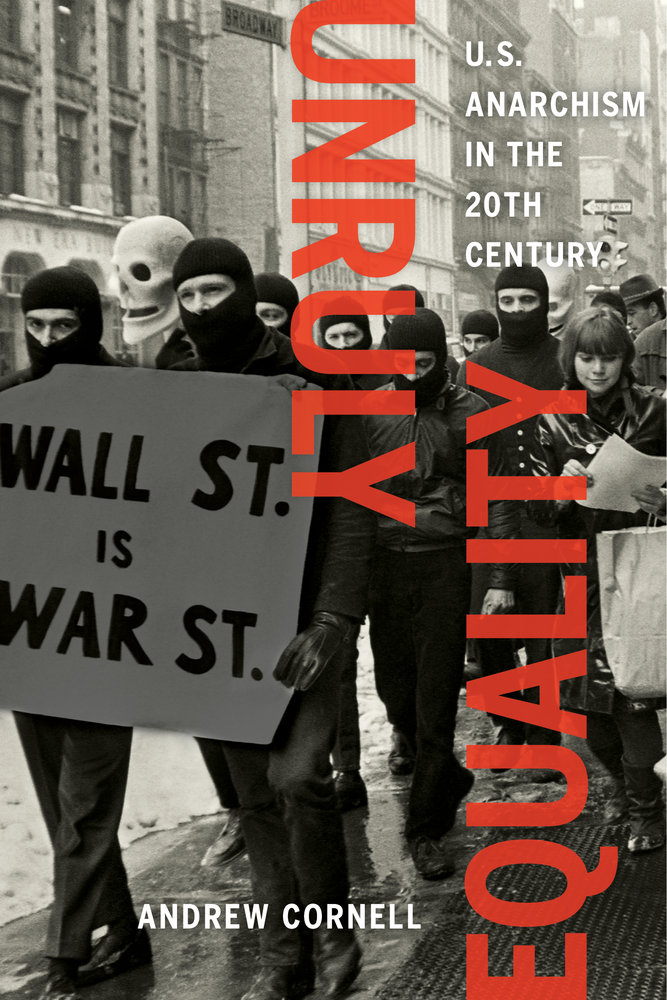

Anarchism's Mid-Century Turn: A Review and Response to Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century, by Andrew Cornell (University of California Press, 2016) by Kristian Williams

Part One

Transitions

No matter how one feels about it, the current state of anarchism has represented something of a mystery: What was once a mass movement based mainly in working class immigrant communities is now an archipelago of subcultural scenes inhabited largely by disaffected young people from the white middle class.

Andrew Cornell’s Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century supplies the first convincing account of that transition. Beginning in 1916, just before the Red Scare, and closing in 1972, just as our present movement was taking shape, the book serves as “a prehistory of contemporary anarchism.” Giving particular attention to the middle decades when anarchism seemed to disappear, Cornell uncovers a missing history and finds “a clear line of continuity rather than a defined break.” The line he traces is continuous, but it is not straight. There may not be a gap, but there was most certainly a turn.

Coming of Age: A Review of Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century, by Andrew Cornell (University of California Press, 2016), by Jeremy Louzao

I was 15, living in a suburban middle-class part of Anchorage, Alaska, when the subversive package arrived—my first committed step on the anarchist path.

It was the winter of 1996, and maybe just six months before, some anecdotes from a beloved radical teacher got me curious about a thing called anarchism. Soon enough, I was doodling circle-As in the margins of my notebooks. Then I was trying, through brute force, to make my way through Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky. Then—oh, the most cliché gateway into anarchism for kids of my demographic—I found punk rock. And there, in the insert of one of my first punk albums, I learned about AK Press. Brandishing a 56k modem, a phone, and a few hundred dollars that I got once a year from Alaska’s strange, oil-based dividend checks, I ordered a load of literature and odds and ends: Anarchy by Errico Malatesta. Living My Life by Emma Goldman, The Ecology of Freedom by Murray Bookchin, something about participatory economics by Michael Albert; Situationist pamphlets and grassroots organizing manuals; tiny punkish pins and a slew of garish t-shirts crammed with ironic faux-corporate logos, stenciled fists, and slogans in block letters. I’ll admit that, for a little while, I just basked in my new consumer identity as an anarchist. Then I actually read the stuff and, Wow, I really was an anarchist! From that cacophonous, often inscrutable, mix of texts, I found a personal worldview, ethics, even a spirituality that came to guide the course of my life.

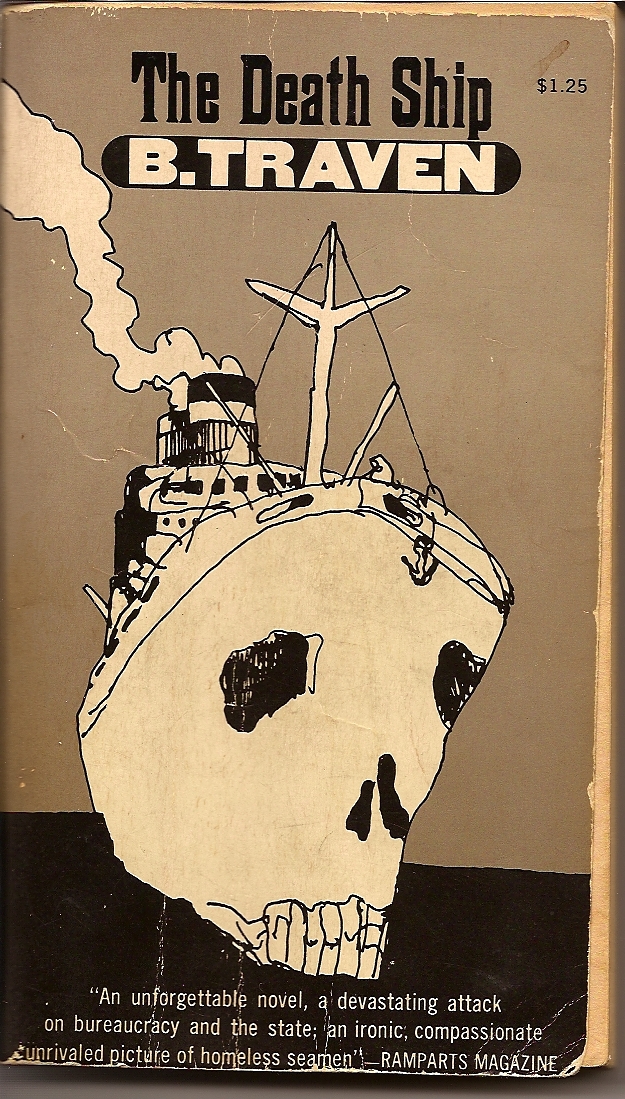

Re-evaluating B. Traven, by John Z. Komurki

The novelist, short story writer, fantasist, and revolutionary B. Traven has been called “the greatest literary mystery of [the Twentieth] century.”[1] “My life story would not disappoint,” Traven himself says in an essay on his breakthrough novel Das Totenschiff (The Death Ship), published in 1926; nevertheless, the author chose to divulge almost nothing beyond scattered, putatively autobiographical references in his novels.

Traven is a pseudonym. The writer’s real name, nationality, date and place of birth, as well as many other biographical details, remain disputed. That is, in part, why he is commonly referred to (adapting the title of one of his collections) as “the man nobody knows.” More, perhaps, than his writing, it is this carefully cultivated mystery, this series of increasingly elaborate smokescreens, ruses and double bluffs, for which B. Traven is most famous today.

Support Radical Writing and Publishing!

If you missed your opportunity to support radical writers and publishing during our recent fundraising campaign, there’s still time to make a donation. The Institute for Anarchist Studies is about to publish issue N. 29 of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory on the theme of Anarcha-Feminisms, in … Read more

Brick by Brick: Creating a World Without Prisons, by Layne Mullett

This essay appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, N. 28, on the topic of Justice. The full issue is available from AK Press here!

Since the publication of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness in 2012, there has been much talk about the need to end mass incarceration. More and more people are speaking publicly about the moral and financial implications of maintaining the world’s largest prison system. However, what it means to end mass incarceration, and what it would take to end it, is less clear.

Mass incarceration plays a central role in maintaining state and capitalist power in the United States, and abolishing the prison system must play a central role in movements for radical change. Mass incarceration allows the state to perpetuate unpopular economic policies that would not be possible in the face of strong resistance movements. While reform efforts might cause the structures of mass incarceration to shift, and lead to decreases in the prison population (as is already happening in some places), a more fundamental transformation is necessary if we hope to see an actual rather than cosmetic shift in the meaning and practice of “justice.”

Our efforts to end mass incarceration cannot be rooted in reform, but must instead address the structural roots that have given rise to the world’s largest prison system. We must create movements that thrive on our differences and build on our strengths. The prison system sits at the nexus of multiple forms of oppression, so we must generate analysis and resistance that is intersectional. Supporting political prisoners, developing the capacity to withstand state repression, and embracing meaningful forms of justice and healing, horizontal models of sharing power, and feminist and queer ways of understanding the multitude of possible futures are all part of this struggle.

Beyond Absolutes: Justice for All

by Megan Petrucelli

Anarchism outlines egalitarian ways of relating. We are encouraged to denounce systems of domination and control in favor of structures of interaction that promote liberation, collectivism, acceptance of differences, and meeting the needs of all. In anarchism, there is an emphasis on inclusivity, listening to … Read more

Breaking the Chains of Command: Anarchist Veterans of the US Military, by Brad Thomson

This piece appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, N. 28, on Justice available from AK Press here. Brad received an Institute for Anarchist Studies writing grant to assist in the completion of this piece.

“War is the health of the State” – Randolph Bourne, written during WW I

“Mutiny is the conscience of war” – Common trench graffiti during WW I

Introduction

War and military occupation are among the most overwhelming demonstrations of state power. Rooted in an anti-state analysis, the anarchist position on geopolitical power struggles between nation-states is unequivocal opposition, especially in reference to international interventions by the US military.

The logical conclusion might be that anarchists should categorically oppose the individuals who are part of the institution of the US military: the troops. Similarly, it may follow that those people who make up the military and veterans would be among the most hostile toward anarchist ideals and action.

However, through my involvement in anti-war movements and anarchist circles over the last ten years, I have encountered a surprising number of anarchists opposed to the US military who are themselves US veterans. For many of them, their experience as GIs (“Government Issue,” a nickname commenting on the fact that service members are treated as government property) played a significant role in forming and developing their anti-authoritarian and anarchist analysis. What follows is based on interviews with a number of anarchists and anti-authoritarians who also happen to be military veterans.

(Chicago, 2012: US military Vets throw their medals back during anti-NATO protests. This is Jacob George, a vet who I had hoped to interview as part of the project, who later took his own life.)

Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin by Janet Biehl, Review by Chuck Morse

Murray Bookchin was a pivotal, polarizing figure in the post-WWII history of anarchism. He put ecology and democracy on the anarchist agenda in a way that was as novel as it is enduring. As a polemicist, he spent decades at the center of crucial debates about history, strategy, and foundational ideals. Even his critics must acknowledge that he made major contributions to the growth and clarification of the anarchist perspective.

Something shifted in the movement when he died in 2006. For the preceding fifty years, his writings had been a point of reference through which we could clarify our views, even when we disagreed with them, whereas now that he was gone we had to make sense of him. Who was he and how had he lived? These are compelling questions for those who had worked with him and for anyone who wants to understand contemporary anarchism.