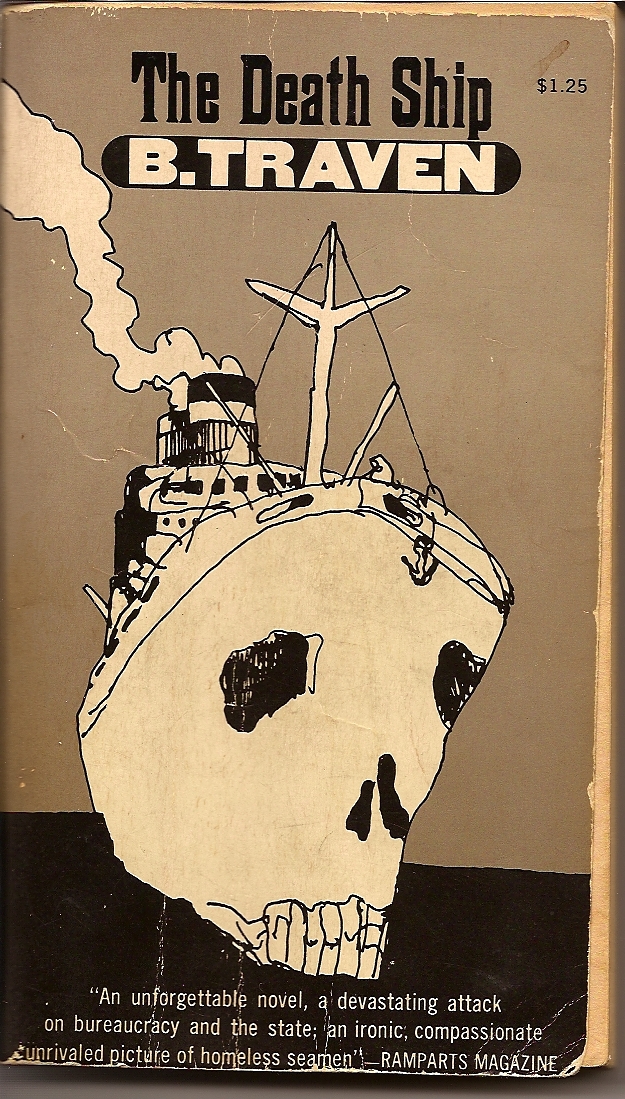

The novelist, short story writer, fantasist, and revolutionary B. Traven has been called “the greatest literary mystery of [the Twentieth] century.”[1] “My life story would not disappoint,” Traven himself says in an essay on his breakthrough novel Das Totenschiff (The Death Ship), published in 1926; nevertheless, the author chose to divulge almost nothing beyond scattered, putatively autobiographical references in his novels.

Traven is a pseudonym. The writer’s real name, nationality, date and place of birth, as well as many other biographical details, remain disputed. That is, in part, why he is commonly referred to (adapting the title of one of his collections) as “the man nobody knows.” More, perhaps, than his writing, it is this carefully cultivated mystery, this series of increasingly elaborate smokescreens, ruses and double bluffs, for which B. Traven is most famous today.

An essential aspect of this mystery was the author’s decision to move to Mexico in 1924. He spent the rest of his life there, and is thus widely considered an essentially Mexican author. This affiliation was made easier by the doubts surrounding Traven’s “true” nationality: he claimed that English was the mother tongue in which he wrote all his novels before they were translated into German. However, linguistic investigations into the different drafts and translations of his works suggest that the picture is more complex than that; in addition, no documentation supporting an American nationality has ever been found.

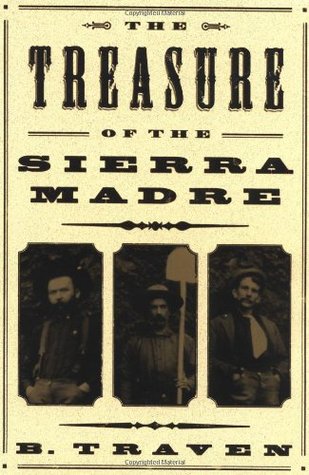

Traven is best known for his novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the six books that together comprise the “Jungle” or “Mahogany” series, a history of the rural proletariat in southeast Mexico. The three defining elements of his writing are its exoticism, its political vision and his gift for gripping storytelling. One of his biographers has called Traven “the ‘gringo’ who introduced Mexico to world literature.”[2] Superficial and inaccurate as it is, this epithet nonetheless encapsulates the common perception of Traven’s place in Twentieth Century literature.

Within Mexico, his championing of the oppressed “Indian” continues to be a touchstone for a certain type of politics: the revolutionaries in his Mahogany novels destroy official documents en masse, just as the Zapatistas were to do when they rose up in 1994. The notion of identity is a leitmotif of his work, in particular the extent to which it is dependent on the possession or loss of certain documents. By investigating how identity is related to questions of statelessness and belonging, Traven reflected both the anarchistic, revolutionary environment in which he cut his teeth, and anticipated many key questions in contemporary geopolitics.

One of the few incontestable facts about the life of the author B. Traven is the date of his death: March 26, 1969, at number 61 Río Mississipi, Mexico City. His ashes were scattered over the Jataté river in the jungle of Chiapas, the Mexican state he most loved.

He arrived in Mexico in the summer of 1924, apparently coming ashore from a steamer. It was in Mexico that he first started to call himself B. Traven (he never explained what the B. stood for.) We could thus take his relocation to Mexico as marking a watershed in the author’s life, both creatively and personally. As his fame grew, Traven adopted different identities and different names, further deepening the mystery in which he was shrouded. His literary success established, a whole industry of commentators, or Travenologists, grew up around the question of his identity: Karl S. Guthke’s B. Traven: The Life Behind the Legends is arguably the most comprehensive and balanced overview of this by now rather tired question. Many people speculated that Traven was the nom de plume of a well-known individual, and some even floated the idea that he was in fact Mexican president Adolfo López Mateos, whose sister was Traven’s Spanish translator.

During his lifetime, the most widespread of the myriad theories regarding his true identity was that B. Traven was a pseudonym for the fugitive German anarchist Ret Marut, and it seems that on his deathbed Traven confirmed this theory. The first documentation we have of Ret Marut dates from 1907, when he was an actor and director at the municipal theatre in Essen, Germany. He later left the theatre and dedicated himself to political agitation: Marut’s first novel (c.1914), never published, attacked the colonial regimes in Indochina, in notable thematic continuity with Traven’s Mexican novels. From September 1917 Marut wrote, edited, and published a shrill and scurrilous anarchist journal called The Brickburner, paving the way for him to become one of the intellectual leaders of the 1919 Bavarian Revolution. Arrested in Munich when it was suppressed, Marut barely managed to escape with his life, and set off on an exile’s wanderings round Europe.

Ret Marut never made it to Mexico. The man he became, B. Traven, did everything he could to disassociate himself from his previous incarnation. The author Traven is thus a kind of palimpsest of different identities. Many Traven scholars work on the assumption that there must be an Ur-identity underlying all of his subsequent reinventions; however, Karl S. Guthke suggests in his biography that Marut/Traven himself may not have been certain of his roots or parentage.[3] Others have commented on the mythomania evidenced in his continual and inconsistent telling of tall tales about his past, in his revolutionary’s instinct for bending the truth, for covering his tracks (it is worth noting that Traven may have been – we have varying birthdates for him – an exact contemporary of Victor Serge, and the two men both moved in the same sordid and dangerous milieu before eventually fleeing to Mexico.) Whatever the case, the writer B. Traven only came into being after he moved to Mexico, and much of his life, and almost all of his oeuvre, took place in that country, making him one of the few foreigners to have earned a place within the Mexican literary canon.

*

Traven’s name is a particularly resonant one in three world literatures: American, German, and Mexican. In Germany he was hugely popular in the mid-Twentieth Century, when was taken as a model for the socially responsible author and thinker; in America, he is known principally as a writer of adventure tales with certain political content; and in Mexico he is one of a select group of foreign authors (among them Mme. Calderón de la Barca and Malcolm Lowry) who are prized for having written incisively and sympathetically about the country.

Traven arrived in Mexico in 1924. Plutarco Elías Calles was president, and Mexican foreign policy was dictated by conflicts related to the extraction of petroleum. The country was increasingly the focus of global struggles concerning questions of imperialism. Why Mexico, in particular? An element of chance undoubtedly inhered, as it always does in the decisions of a fugitive and exile, but there was more at work than serendipity. As Traven himself said in a letter to his editor, “Mexico is already, and will become increasingly so [sic] in the coming two decades, the economic and hence political focal point of capitalist and imperialist world politics, but at the same time it is, curiously, also the focal point of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist world politics.”[4]

A rather facile comparison is often drawn between Traven and Rimbaud. According to this comparison, Traven turned his back on the world in order to lose himself in the jungles of Mexico. The opposite is true. Traven was a natural demagogue and agitator; his life was given over to selflessly and often unprofitably advancing his political convictions. There is a direct continuity between the roles he played in Europe and the role he played in Mexico. Indeed, the political philosophy he espoused was premised on the idea of universality, and on the notion that the indigenous people of Mexico and the peasants of Siberia, say, were fighting essentially the same battle.

Tampico, where Traven lived after arriving in Mexico, was an important center for the Industrial Workers of the World, the anarchist-syndicalist labor union the members of which were known as Wobblies. Working as a day laborer in the region around Tampico, Traven met Wobblies as a matter of course. One edition of Traven’s first novel was titled The Wobbly, and the descriptions of their activities and attitudes in his early novels constitute a valuable source for the study of Mexican social history. We know, too, that he read El Machete, the radical journal founded by Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, among others.

In later years Traven spent more and more time in Mexico City, there consorting with radical circles that included Rivera and Siqueiros, as well as Edward Weston, Tina Modotti and the American journalist Carlton Beals. This group was active in numerous political campaigns, among them the US intervention in Nicaragua (1912 to 1933), the Calles government’s social reforms, foreign involvement in oil, the role of the church, and land reforms. All of these themes are touched on, often repeatedly, in Traven’s novels, showing the extent of his engagement with contemporary Mexican politics.

Mexico also spoke to Traven on a personal level. We read on the first page of Die Baumwollpflücker (The Cotton-Pickers, 1926), his first Mexican novel, that in Mexico “it is considered tactless, in fact insulting, to question someone about his name, his occupation, his origin and plans.” Whether he was projecting his own vision or responding to a genuine cultural value, it is clear that Traven felt at home in Mexico, and moreover that it was the ideal place to continue his game of anonymity and reinvention.

We have little data with which to reconstruct the author’s first years in the country. For the first six he lived in a shack in the bush thirty-five miles outside Tampico. Here, plagued by mosquitos, tarantulas, and snakes, Traven wrote his first Mexican stories and novels, among them The Cotton-Pickers, in the shadow of a nearby Mayan pyramid. Der Schatz der Sierra Madre (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre), the novel he is most remembered for, was also written here in 1927. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is less overtly political than his other works, centered as it is on the traditional tropes of adventure stories. It tells the story of three American prospectors, who are eventually corrupted by the large quantity of gold they amass: the novel closes with the gold dust being blown away in the wind. During these years Traven worked in different jobs, among them cotton picking, accruing experiences which were reworked into his fiction. He also tried his hand at journalism, without much commercial success (the National Geographic rejected a piece by ‘Mr. Traven Torsvan’ on ‘The Tzotzil Indians and Their Neighbors.’)

In 1926, as the photographer B. Torsvan, Traven took part in an archaeological expedition to Chiapas. He saw Chiapas as a microcosm of many of the social and political problems afflicting the world. In an essay he celebrates “the courage, the dedication, the sacrifice—unknown and unconceivable in Europe—with which the proletarian Indian in Mexico fights for his liberation.”

It was inevitable that he should equate the Mexican “Indian” with the European proletariat; he speaks elsewhere of “pure, ancient Indian communism,” and he considered the Lacandones indigenous group his “brothers” and “soul-mates”. Indeed, it is his perspective on, and defense of, indigenous people that may well prove to be Traven’s most lasting literary legacy.

Until the revolution … the Indian was viewed as an animal which could talk, laugh, and cry. It was expressly denied—by the state, the church, and in literature—that the Indian had a soul… . I am confident in my hopes that I have succeeded in revealing to the European … that the Indian displays no differences of any sort from our race in regard to his feelings and emotions.

Although Traven regarded the Mexican Revolution as the moment when the “Indian” was first permitted a soul in his native country, there can be no doubt that in Mexico there was great resistance to this idea. For much of his lifetime Traven’s writings were not recognized by the Mexican literary establishment, and some critics have argued that this is due precisely to classist and racist values espoused by reactionary elements in the Mexican cultural world, even several decades after the revolution.

A unique position in Traven’s oeuvre is held by Land des Frühlings (The Land of Springtime, 1928), the only non-fiction book he ever published. It constitutes a description of his travels in Chiapas, and a showcase for his political ideology. It is both an exotic travelogue—taking in geography, folklore, ethnology, history, and archaeology—and a timely critique of the conflicts that arise when big industrial powers impinge on the sovereignty of less-developed nations, closing with an appeal to the Mexicans “not to fall asleep again” following the 1910 revolution. The author himself recognized that this book had dated significantly even within his own lifetime (he makes free and easy use of the term “race”, for example), and subsequent editions were heavily edited.

Kunst der Indianer (Art of the Indians) was a document that Traven put together in 1929 but never published. It is a rich and detailed text, focused principally on native material culture, which collates diverse illustrations and contributions from different authors. Traven asserted that much of the material therein had been surpassed, and for that reason he decided not to publish it, although some chapters were published in German, and in 1974 the Mexican magazine Siempre published two translations from it, ‘Las Pulquerías’ and ‘El niño mexicano como artista y creador’. It is interesting that Anita Brenner’s Idols Behind Altars, the book often credited with bringing traditional Mexican art to an international audience for the first time, was published in 1929—we can see that Traven was thus at the forefront of a shift in attitude towards indigenous culture.

In 1930 Traven moved to El Parque Cachú, a restaurant and cashew orchard just outside the (then) sleepy coastal town of Acapulco. He was to live there for 25 years. His fame, above all in the German-speaking world, was well established by 1930, and by 1936 the total circulation of his works in that language was nearly half a million. This success gave him greater freedom to concentrate on his writing, and between 1931 and 1940 his six Mahogany novels appeared, from The Carreta (1931) to General from the Jungle (1940).

It is thought that he first heard about the Mahogany monterías, or forced labor camps, from his guide Amador Paniagua, who had spent seven years in them as an indentured laborer. As with much of Traven’s work, the specific local setting is used to articulate universal political problems, among them repression, capitalist exploitation, and social injustice. Traven argued that the Mahogany novels reveal “the true causes of the revolution and rebellions which have stirred up the Mexican people for twenty years.”

In the mid 1930s, the Nazis paid Traven the great compliment of blacklisting and burning his novels. His income from the German market dried up, and Traven was obliged to turn to American and, slightly later, Mexican readers. In 1941 the first authorized Spanish translations of his novels were published in Mexico, made by Esperanza López Mateos, who became not only Traven’s translator, but also his private secretary, agent and, before her death ten years later, his closest friend. He and Esperanza even planned to found a publishing house together (named Tempestad, Storm) but the plans came to nothing. His major works all appeared in Spanish between 1941 and 1951.

Following the war, Traven wrote a number of political essays, one of which argued for the inevitability of a Third World War, just six months after the Second had wound up. He highlights, presciently, that the peacetime draft and expansion of the American navy could only give rise to another conflict, although he failed to predict the ‘cold’ nature of that conflict. As Guthke underlines, Traven’s voice, “a lone cry” in Germany, “could count on resonance in Mexico.” Indeed, it was this striving for “resonance” which defined the final stage of Traven’s life. The Mahogany series was not as successful as his earlier novels, and he began to cast around for a way to spread his message further, finally hitting on the cinema, then in its ascendance as a mass medium in Mexico.

Most of the rest of his life was given over to scriptwriting. In 1949, John Huston made the Academy Award-winning adaptation of his Treasure of the Sierra Madre, starring Humphrey Bogart. In his autobiography, Huston describes his mysterious meetings with Hal Croves, Traven’s ‘agent,’ who was almost certainly the man himself. The Sierra Madre movie gave rise to a surge of interest from the press that culminated in Mexican journalist Luis Spota’s 1948 revelation that the wiry, blue-eyed gardener in the Acapulco rest house was in fact Traven. Other cinematic adaptations followed: The Rebellion of the Hanged (screenplay by Hal Croves, filmed by Gabriel Figueroa) was a notable success in 1954.

From the completion of the Mahogany series to his death, B. Traven’s main literary activity was that of revising his novels for English-language editions, often expunging specifically German references: Apart from a number of short stories, the only post-war publications by Traven were the universally reviled Aslan Norval (1960)—so bad that people doubted it was his—and Macario, a sort of indigenous fable that the New York Times declared the best short story of 1954.

In 1957 Traven married Rosa Elena Luján, his wife until his death. He spent his last years in Mexico City, where his friends included the wife of John Kenneth Turner, author of Barbarous Mexico (1911), artists, cinema people, and other members of the capital’s intellectual elite. In 1963, Short Story International called him “Mexico’s most famous writer.” Guthke even goes so far as to describe him as “the unofficial national laureate.”[5] And in 1967 a Stockholm newspaper campaigned for B. Traven to be awarded the Nobel Prize.

*

Critical studies of B. Traven are predominantly concerned with the question of his identity—this despite the fact that Traven strenuously argued that it was immaterial, and often expressed his scorn for “literary sleuths.” We will never know whether the dense fog of secrecy surrounding him corresponded to some psychological necessity, or was merely a marketing ploy, but the fact is that his ‘true’ background is of only tangential importance in understanding his writing. It is thus regrettable that the vast majority of the critical literature on his work is overwhelmingly concerned with chasing down red herring after red herring.

In total, B. Traven published twelve novels, one book of reportage and numerous short stories; his writing has been translated into more than thirty languages. He enjoyed huge international success, above all in the period following the Second World War. Many readers are drawn to his novels, in particular The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, his most well-known work, for the exoticism of their settings and characters, or the high adventure of their plots. Indeed, John Huston’s film of Sierra Madre foregrounds these aspects of Traven’s work. And it is undoubtedly true that the plot and characters of his books serve principally as vehicles to propagate his message.

Speaking of himself in the third person, Traven asserts in an essay that “he does not write fairy tales for adults to help them fall asleep more easily. Rather, he writes documents, that is all; documents which he puts in the form of novels to make them more readable.”[6] This modus operandi no doubt explains many of the flaws that his writing exhibits: its often overblown sentimentality, for example, or the heavy-handedness of his symbolism.

From the first, critics have made no bones about the fact that, despite his immense talent, Traven wasn’t much of a stylist. His language is often loose and careless, and his plotting jarring or sloppy; in addition, he falls all too easily into a virulent rejection of “European” or American values, which is in turn balanced by an tendency to idealize the “Indian” as a kind of anarchist noble savage. This tendency is most concisely shown in his Die Brücke im Dschungel (The Bridge in the Jungle, 1929), set in the foreign-owned oil fields of Tamaulipas. The novel relates a single episode, which Traven uses to set European-American capitalism against the communitarian self-sufficiency of Indian communities.

Traven’s texts are rarely complex in intent or execution. He was essentially a political writer, his works animated by the voice of the non-affiliated “philosophical anarchist” offering alternatives to Western ideas. Although it fluctuates, and the ideas it propagates become less strident over time, it is this voice that establishes a continuity across his oeuvre. (It is, however, almost absent in his final novel, Aslan Norval, another reason many people doubted its authenticity.)

Within continuity, however, we could divide Traven’s creative life into three periods. If we accept, as it seems we must, the theory that Ret Marut was indeed Traven, then the first period of his life corresponds to the years that Marut spent as an anarchist pamphleteer in Germany. The second phase begins in Mexico, and continues until after the Second World War: this phase was, of course, the most productive, and it was during it that he wrote the vast majority of his novels. The third phase begins with Traven turning his back—whether deliberately or otherwise—on books, and focusing instead on writing for the cinema, and collaborating on movie adaptations of his work. The third phase concludes with his death. Artificial as it may be, this division all but draws itself, and provides us with a useful schemata with which to understand his life.

Michael L. Baumann is one of few ‘Travenologists’ to have applied a consistently rigorous approach to the academic study of Traven’s work and politics; his 1977 essay on Land des Frühlings (The Land of Springtime) is still the best piece on the subject. Of interest, too, is his consideration of the extent to which Traven might be thought of as a ‘proletarian’ writer.

Taking as his starting point The Death Ship, Traven’s first novel, Baumann examines the anti-capitalist and anti-nationalistic stances that Traven’s work embodies. He makes the important distinction that, being neither a socialist nor a communist, for Traven the struggle of the workers was not a class struggle in the most common sense of the term; he thought that ethnic divisions and antagonisms in Mexico required a more nuanced analytical apparatus than one based on socioeconomic difference alone. (Baumann 1985, 83f) He mentions both Dickens and Upton Sinclair (with whom Traven corresponded) as possible models, and makes the point that, like Dickens’, Traven’s characters are rarely unambiguous, and the ideas or concepts his novels lay out are rarely completely unequivocal. An unspoken theme in Traven’s work, Baumann says, is the uncertainty that humankind is indeed capable of improving its lot and emerging from (rather than simply getting used to) suffering. Baumann carefully traces this radical uncertainty from The Death Ship through to the Mahogany cycle, arguing that it is what makes Traven a more nuanced writer than the simple ideologue or polemicist.[7]

Too often, questions such as these are folded into speculations about Traven’s identity. But as Traven himself repeatedly asserted, an understanding of his political beliefs does not hinge on whether he was the anarchist Ret Marut: they are to be found in plain sight, in his writing. Baumann’s conclusion is that the only term which can usefully applied to Traven’s philosophy is anarchism.[8]

Traven could also be considered an avant la lettre anti-colonial writer. Ret Marut’s unpublished first novel, set in Indochina, constituted a caustic attack on French exploitation of the region. Traven’s Mexican novels are anti-colonial in two senses: the first, most obvious, is his criticism of the exploitation perpetrated in Mexico by foreign, principally American, companies. The second, more diffuse sense stems from his solidarity with indigenous people. Although the workers in the camps described in the Mahogany novels are exploited by other Mexicans, rather than external powers, he makes clear that the power structure which permits this exploitation is directly derived from the era when Mexico was first colonized. Few writers before Traven articulated as forceful a perspective on the different forms of colonialism, or were as alive to its many shifting and insidious manifestations.

It has been noted that the author considered himself to be above all a Mexican writer: his widow reported that he would often claim that “I am more Mexican than you are.”[9] And some contemporary voices asserted that he had penetrated deeper into specifically Mexican questions—in particular the lives and struggles of indigenous people—than many authors who had actually been born in the country. Writing in 1951, critic Manuel Pedro González argues that Ramón Rubín was the only Mexican author who approached Traven in terms of identifying with the indigenous people, whilst all others wrote “from outside, from a greater or lesser distance, without emotional complicity.”[10]

Traven’s uncompromising tone perhaps explains why the Mexican literary establishment waited several decades to take his work seriously. The written word, and above all “Literature,” was the preserve of the urban, educated classes until well into the twentieth century. Manuel Pedro González argues that Traven’s agenda led to him being marginalized by the Mexican literary establishment, at least in the years leading up to his death. By 1967, however, he had been included in Aurora M. Ocampo and Ernesto Prado Velázquez’ Diccionario de escritores Mexicanos (Dictionary of Mexican Writers), where he is hailed as “a genius of indigenism.”

By examining critical receptions to Traven’s work in both Mexico and abroad, we can get a sense of how relevant and challenging a writer he was and remains. While we may choose not to classify him as an anarchist thinker per se, his books articulate and develop many key anarchist perspectives. For the radical and revolutionary content of his ideas to be appreciated clearly, Traven must be engaged with as much more than a writer of exotic adventure stories or tantalizing literary mystery.

John Z. Komurki is founding editor of Mexico City Lit, a non-budget digital journal and press, mainly dedicated to publishing Mexican literature in translation. He co-edited the bilingual anthology Poets for Ayotzinapa, and is the translator of Mexican Poets Go Home (forthcoming from Bongo Books) as well as author of Stationery Fever (forthcoming from Prestel).

Bibliography

Baumann, Michael L. ‘B. Traven: Realist and Prophet’. VQR, Winter 1977, Volume 53. Available at: http://www.vqronline.org/essay/b-traven-realist-and-prophet

Baumann, Michael L. B. Traven. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985.

Bigas Torres, Sylvia. La narrativa indigenista mexicana. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara/Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1990.

González, Manuel Pedro. Trayectoria de la novela en México. Mexico, Botas, 1951.

Guthke, Karl S. B. Traven: The Life Behind the Legends. Lawrence Hill Books, USA, 1991.

Monsiváis, Carlos. A ustedes les consta. Antología de la crónica en México. Mexico: Era, 2006.

Ocampo de Gómez, Aurora M., and Velázquez, Ernesto Prado. Diccionario de escritores mexicanos. México: UNAM, 1967.

Rall, Dietrich. ‘B. Traven, ¿un autor Mexicano?. In: Von Hanffstengel, Renata (ed.). México, el exilio bien temperado. Mexico: UNAM, 1995.

Schürer, Ernst, and Philip Jenkins. B. Traven: Life and Work. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987.

Stone, Judy. The Mystery of B. Traven. Los Altos: William Kaufmann, 1977.

Zogbaum, Heidi. B. Traven: A Vision of Mexico. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1992.

Notes

1 Karl S Guthke, B. Traven: The Life Behind the Legends (Lawrence Hill Books, USA, 1991), 12.

2 Guthke, B. Traven, 5.

3 Guthke, B. Traven, 103.

4 Guthke, B. Traven, 184.

5 Guthke, B. Traven, 396.

6 Guthke, B. Traven, 194.

7 Michael L. Baumann, B. Traven (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985), 95ff.

8Baumann, B. Traven, 95ff.

9 In Dietrich Rall, ‘B. Traven, ¿un autor Mexicano? (in Renata von Hanffstengel (ed.), México, el exilio bien temperado. Mexico: UNAM, 1995), 95.

10 Manuel Pedro González, Trayectoria de la novela en México (Mexico, Botas, 1951), 320.