Several factors played into our collective decision not to run a print issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory for the current year. We sincerely thank all inquiries and submissions sent for what was hoped to be an issue on Play. A call for submissions for a Beyond The Crisis print issue of Perspectives (2018) is here.

This is an article written by two Wobblies in response to our call for Play essays. These organizers bridge the gap between play and the practice of organizing skills via educational skits and fun activities led by the New Junior Wobblies, the young members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The IWW globe logo holds three stars representing Education, Organization and Emancipation. This article looks at Recreation – a fourth star – from challenging uneven relations of power, to making joy central to organizing against capitalism, regardless of age.

Shortly after a wave of government repression and internal splits nearly destroyed the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as a functioning labor organization, a group of Wobblies felt the immediate need to find new ways to raise the next generation of revolutionary unionists. As a part of solidarity support for striking IWW coal miners in Colorado, children of union members were invited to join an IWW organization of their own. These Wobbly kids formed “locals” to organize support for their striking parents, and alongside them, develop a rudimentary understanding of the world and how they might soon be a part of organizing to change it. To the IWW tripartite motto, “Education, Organization, Emancipation” they added “Recreation,” and in 1927, the Junior Wobblies Union was born.

Perspectives

What is Anarchism?

Lara Messersmith-Glavin and Kristian Williams, of the Institute for Anarchist Studies and Perspectives on Anarchist Theory journal collective, and Ayme Ueda, of the Black Rose Anarchist Federation / Federación Anarquista Rosa Negra, recently appeared on X-RAY FM in Portland, Oregon. The show is called Group Therapy, hosted by Natalie Sept. This episode features an hour discussion of topics including what anarchism is, what anarchists want and do, anarchist critiques of the world, and challenges anarchists face. Listen in below!

Lara Messersmith-Glavin and Kristian Williams, of the Institute for Anarchist Studies and Perspectives on Anarchist Theory journal collective, and Ayme Ueda, of the Black Rose Anarchist Federation / Federación Anarquista Rosa Negra, recently appeared on X-RAY FM in Portland, Oregon. The show is called Group Therapy, hosted by Natalie Sept. This episode features an hour discussion of topics including what anarchism is, what anarchists want and do, anarchist critiques of the world, and challenges anarchists face. Listen in below!

Perspectives available in Canada!

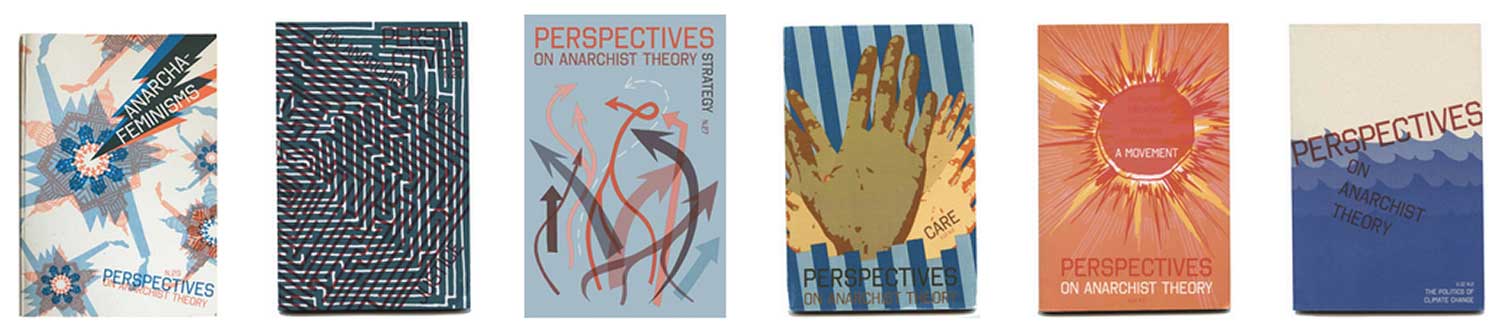

The current anarcha-feminisms issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (n. 29), and all back issues, including:

Justice, Strategy, Care, Movements, and Climate, are now available in Canada, from Kersplebedeb Leftwing Books!

Free Unicorns: A Review of Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and Desire, edited by C.B. Daring, J. Rogue, Deric Shannon, Abbey Volcano, by Kristian Williams

This book review appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29) available from AK Press here!

This book review appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29) available from AK Press here!

Queering Anarchism. The title suggests a process, something in motion, developing, unfolding, undefined, unsettled. Indeterminacy is part of the point of the subversion of categories, an opening of possibilities, simultaneously emphasizing and easing difference. What was once hidden becomes apparent; what was once obvious becomes absurd. Both the anarchic and the queer challenge the status quo. Both expand our sense of the possible, enlarge our idea of freedom. What happens when these two mercurial concepts come into contact?

In making the attempt, Queering Anarchism accomplishes something remarkable, providing a good, quick orientation to anarchism and a short introduction to queer politics and queer theory. And by relating the two, it enacts a kind of intervention into each. The book’s twenty-one chapters show that queer politics needs an analysis of class and power, and that the anarchist critique of capitalism and the state has much to gain by incorporating questions of gender and sexuality. The contributors consider the multiple ways that power relations shape our sex lives, our gender expressions, our family arrangements, our sense of self and belonging, and even our desires, fantasies, and entertainment. Conversely, they also explore the ways that freedom might change those things and moreover, how changing them might in turn transform our understanding of freedom. As Jerimarie Liesegang writes in “Tyranny of the State and Trans Liberation”:

Whereas anarchists and anarchist theory need to look at struggle on the conceptual level that queer theory provides, queer theory needs to be coupled with anarchism’s critique of structural domination, such as the state and capitalism. (96)

If that sounds a bit like a dare, it is a dare worth taking.

Radical Language in the Mainstream, by Kelsey Cham C.

This essay appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29), available here, from AK Press!

As a person who did not come to radical perspectives from academia, I’ve had quite the challenge trying to find community with people whose politics I respect.

I grew up in the suburb of Newton, Surrey, territory of the Katzie, Kwantlen, Semiahmoo and Tsawwassen peoples. I was an athlete and last-minute procrastinator who never understood why school should be taken seriously. Though I read newspapers every day, I didn’t have the words to describe the injustices I could see and feel. My lack of trust in the school system, and my dwindling trust in the politics of high level sports led me to believe I didn’t need validation from institutions. In grade 8, I started skipping class to find freedom. A couple of years later I found myself getting into hard drugs and failing classes. Eventually, I failed out of high school completely and was pretty proud about it.

More than a missing diploma, more than my struggle with addiction, my biggest barrier to finding community in radical circles was a lack of exposure to their social expectations. I found very little compassion and support, and was often met with harsh judgment. Coming into these communities, I felt not smart enough and like an outcast. It took me years to understand the everyday language used in radical activist communities. Some words were long, some were short, but everyone said these words so casually I thought I would come across as stupid to ask what they meant. I’d go to talks and workshops, and some really smart dude would talk for an hour and then open up the space for questions. I remember feeling so lost by the jargon that by the end, I didn’t even know what the talk had been about. Clearly, I wasn’t going to ask the questions running around in my brain. “What do you mean by colonization?” “What is queer theory?” “Who is Marx!?” “Why are you speaking to us like my boring geography teacher?”

Coming to Terms: Rethinking Popular Approaches to Anarchism and Feminism, by Theresa Warburton

This essay appears in the anarcha-feminisms issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29) available here from AK Press! Theresa is a past recipient of an Institute for Anarchist Studies writing grant. To save our movements, we need to come to terms with the connections between gender … Read more

Abolishing the “Psy”-ence Fictions: Critiquing the Relationship Between the Psychological Sciences and the Prison System, by Colleen Hackett

This essay appears in the current anarcha-feminisms issue of Perspectives, N. 29, available here, from AK Press!

Tiana is crying. She walks into the room, a large, powerful woman wearing a bland ensemble of a faded green top with similarly colored pants. The silent tears on her face are enough to quiet the many scattered conversations happening among us. Many of us try to make eye contact with Tiana, waiting for her to tell us what is wrong. She doesn’t speak. She doesn’t look at anyone. She sits and stares.

We’re all sitting in a classroom in a women’s prison. The space is filled with remedial educational materials for GED students, collages with magazine cutouts of models and vacation getaways, and clichéd motivational posters that inspire the incarcerated to become “ambitious” and “dedicated.” In the moments of silence that follow Tiana’s entrance, I’m reminded of the poster on the wall that lists the amendments to the US Constitution. On this poster the legendary constitutional change, the thirteenth amendment, only includes the part that formally abolishes slavery and does not include the part that says, “Except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Every time I encounter suffering in that room, including my own, I remember that sterilized, whitewashed version of history hanging on the wall and cringe. And I rage, quietly.

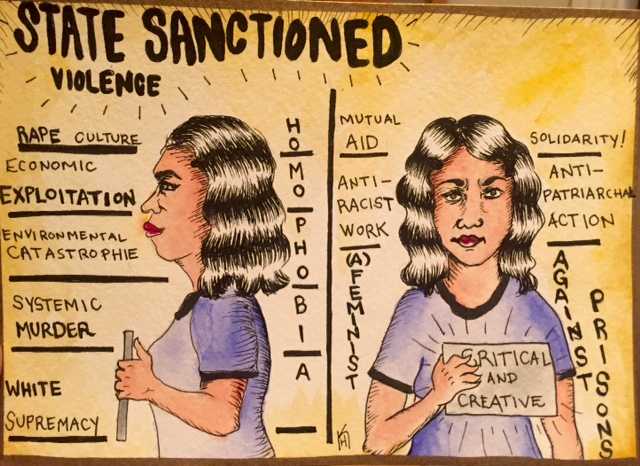

Until All Are Free: Black Feminism, Anarchism, and Interlocking Oppression, by Hillary Lazar

Black feminism has a particularly deep resonance with anarchist understandings of mechanisms of power, which similarly foreground a linking across all systems of domination. Again, this is important to note, so as to ensure that the impact of Black feminism on contemporary anarchism is not overlooked. This currency across the two schools of thought is also notable, however, as it very well may be the coming together of Black feminism and anarchism that is encouraging the shift in orientation away from a more fragmented conceptualization of struggle, and towards the idea of our struggles as interdependent. And, especially given the increased presence of anarchism in mobilizations since the Zapatista uprising in 1994, it seems plausible that the confluence of these streams of thought is having a powerful combined impact on radical political thought and culture.

Critique and Renewal: The Institute for Anarchist Studies at Twenty

Chuck Morse

I played a pivotal role in the early history of the Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS). I conceived of it, drafted all the founding documents, selected the initial Board of Directors, led early fundraising campaigns, and anchored it as a whole. Although I have had … Read more

Anarcha-Feminisms, Introduction

by the Perspectives Collective

This is the introduction to the anarcha-feminisms issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N.29). The whole issue is available again from AK Press here! Ok, editorial collective. Let’s talk this through. So, what are anarcha-feminisms and why do they need their own Perspectives issue? … Read more