This essay appears in the current anarcha-feminisms issue of Perspectives, N. 29, available here, from AK Press!

Tiana is crying. She walks into the room, a large, powerful woman wearing a bland ensemble of a faded green top with similarly colored pants. The silent tears on her face are enough to quiet the many scattered conversations happening among us. Many of us try to make eye contact with Tiana, waiting for her to tell us what is wrong. She doesn’t speak. She doesn’t look at anyone. She sits and stares.

We’re all sitting in a classroom in a women’s prison. The space is filled with remedial educational materials for GED students, collages with magazine cutouts of models and vacation getaways, and clichéd motivational posters that inspire the incarcerated to become “ambitious” and “dedicated.” In the moments of silence that follow Tiana’s entrance, I’m reminded of the poster on the wall that lists the amendments to the US Constitution. On this poster the legendary constitutional change, the thirteenth amendment, only includes the part that formally abolishes slavery and does not include the part that says, “Except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Every time I encounter suffering in that room, including my own, I remember that sterilized, whitewashed version of history hanging on the wall and cringe. And I rage, quietly.

Three other “outsiders” and I co-facilitate a class for survivors of intimate partner violence at a women’s prison. Throughout this essay, I’ll refer to “outsiders” and “insiders”—the chief distinction between the two labels is spatiality and refers to which side of the prison wall one resides on. The outsiders, including myself, are the nonincarcerated facilitators who go to the prison on a weekly basis and have been doing so for about two years. Our small, nonhierarchical collective of outsiders is made up of people who identify as women, artists, mamas, educators, scholars, and/or organizers, and most of us have histories of trauma, abuse, drug and alcohol misuse, or criminalization. The insiders are the incarcerated facilitators and participants who steer the curriculum and lead the popular-education-style classes. The people on the inside of the prison walls have less spatial and social freedoms than the outsiders, and the group makes every attempt possible to close this distance by centering the class’s focal point on the voices, experiences, wisdom, and triumphs of the insiders.

We are based out of a prison in the Rocky West region that houses about a thousand people in various custody levels. As is typical in nearly all US prisons, there is a gross overrepresentation of Black, Brown, Native, and bi/multiracial peoples. This women’s prison, much like other women’s prisons, has a population with extremely high rates of reported and unreported trauma, past and/or ongoing physical and mental abuse, and sexual violence. There are estimations that 65-85 percent of people incarcerated in a women’s jail or prison have histories of abuse compared to 30-45 percent abuse and sexual violence rates among non-incarcerated women.1 Most of the people at this prison are poor. As many as 80 percent of those incarcerated at a women’s prison meet the criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder. Many are mothers and a good majority are single mothers of children under eighteen, which can have devastating consequences for children, especially if they are funneled into the foster system. It is acutely clear that women’s prisons contain a community of people who are at the lowest end of the social and economic strata: those who are considered disposable and expendable, those who have been historically debased by gendered and racialized violence as well as colonial conquest and aggressive neoliberal capitalism, and those who will suffer from the scarlet letter of incarceration. This scarlet letter or “mark” also signals other assumptions about a person to dominant society, branding the punished as inferior (biologically, culturally, or both), tainted, and irredeemable.

Social death, a concept most famously applied in describing the psychological effects of slavery in the US, is a consequence of the master’s total control over a slave’s body, labor, and identity.2 The slave becomes wholly dependent upon the master after the social, genealogical, and historical alienation she experiences. In some instances, slaves who have experienced this sudden social death internalize a sense of zero self-worth, and adopt attitudes of blame and hate for the self and others who are like her. Although governmental and prison officials would like to obscure the direct similarities between the social death of slavery and the social death of prison, the parallels are striking. The manifestation of social death in the prison system is the ineligibility to personhood before, during, and after incarceration.3 The very social institutions that claim to safeguard those who are the most “deserving” of protection have failed the women who find themselves in prison. Better-resourced and more-privileged women (oftentimes middle-class white women) benefit from domestic violence state services and the judicial system in ways that others do not. In contrast, the sex workers, the drug users and “addicts,” the poor, the queer, the women of color, and the ones who were shut out of mainstream educational opportunities and legitimate economies are left to fend for themselves. These are the women whose bodies and localities bear signifiers of criminality, as judged by mainstream society and the court system, by being nonwhite and/or residing in disenfranchised and poverty-stricken neighborhoods. The legal system consequently becomes the master that attempts to strip women of their personhood. The criminal legal system sorts out the “real victims” from the “criminals.” That is, women (and men, for that matter) who have simultaneously been harmed and have committed harm are not regarded as people with complex histories but rather as archetypal criminals with no “right” to helping services or freedom from institutionalized violence. Criminalized peoples are the disposable, the unworthy. The insidiousness of this social death process is the extent to which the myths of worthlessness have been absorbed into the stories that the incarcerated tell about themselves.

The outside facilitators bring programming into the women’s facility to, at the very least, mitigate women’s sense of social death. We ideally hope to mobilize prisoners’ resistance to the brutally repressive circumstances in which they find themselves. In doing this, our class explores themes of oppression, power, and patriarchal and white supremacist violence, as well as liberation, resistance, and community organizing. The insiders frequently take the lead in facilitating healing circles in which prisoners voice their personal struggles and share insights and wisdom. Many of the class participants express that the act of articulating their problems helps to bring closure and lessen their pain. In addition to sharing our personal burdens, we also prioritize a politicized curriculum in which participants can connect these burdens to collective struggles. We have found that this process enhances our connectedness and empowers the group to think of ways to oppose and defend against domination. Our group often studies histories of struggle and people’s movements for inspiration and proof that the so-called “power-less” are indeed brimming over with power and vitality. Our approach emphasizes the importance of merging the political and the personal, while honoring the resilience that we each hold. Therefore, we often operate within the messy confines of personal traumas, internalized oppression, and institutionalized violence that can lead to unexpected circumstances in the classroom. For example, our agenda on the next to last class was concerned with an organizing project to address the commissary markups at the facility (for instance, a ten cent bag of ramen sells for fifty cents), and we had not planned on Tiana’s tears and need for support.

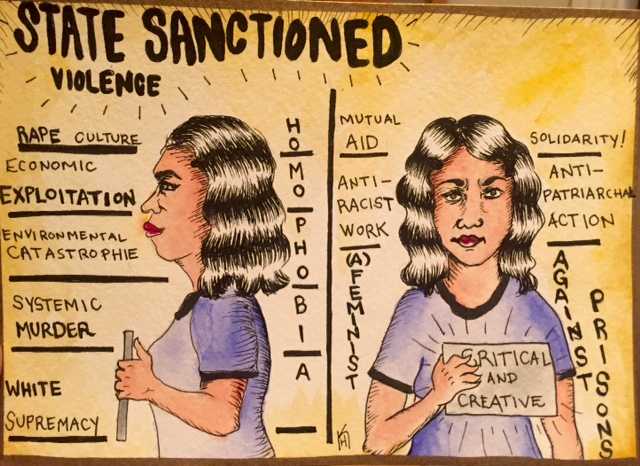

In our adoption of an anti-oppression praxis, we prioritize intersectional frameworks. This way of analyzing power is especially necessary for understanding the nuances of domination and how control is exercised through race, class, gender, sexuality, ableism, and citizenship, to name a few. The marriage of anarchism and feminism, particularly queer, women of color, and transnational feminisms, necessitates the dismantling of all oppressive structures. An essential part of this kind of revolutionary project demands that the interconnected structures of patriarchy, transnational capitalism, white supremacy, heteronormativity, and Western imperialism be recognized, as they act differently through and upon people with varied identities. Although traditionally, mainstream feminism has concerned itself with the struggle against gender oppression only and the differences between the “universal” categories of “women” and “men,” a relevant feminist political project understands how other social markers and contexts trouble gender as a singular analytic category. As Sandra Harding points out, “There are no gender relations per se, but only gender relations as constructed by and between classes, races, and cultures.”4 I would add to this list: sexuality, ability, and legal status, which are particularly relevant when talking about incarcerated women. As Patricia Hill Collins has pointed out, these interlocking structures form a matrix of domination—the interconnection of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, nationality, and so on—that differentially, yet incisively, acts upon people depending upon where they are located in the power structure.5

The writings of Audre Lorde are acutely attuned to the varying ways in which the tools of domination operate on and through people. Lorde, especially in her exacting critiques of status quo (white, heterosexual, “first-world,” class-advantaged) feminist theory, discusses the need to explore the personal as well as the political and never to separate the two.6 Her radical feminist propositions had been preceded by Second Wave mainstream feminism a few years earlier, namely in the old adage of “the personal is political.” That is, the experience of gendered oppression is one that is commonly ignored, laughed about, silenced, or dismissed. Lorde reminds white feminists in particular that their personal experiences cannot properly represent the daily manifestations of racialized and colonial violence that women of color personally experience. She proposes a radical and non-reformist framework through which, by adopting an intersectional politics, mainstream feminists might move away from their personal lives as women who benefit from the “master’s tools [of domination and privilege]” and towards a critical consciousness of multitude, difference, and inclusivity. “Then, the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices.”7 This illustrates the point that not only should the personal be political, but also that relevant political projects should make room for the “messiness” of our internal lives, and that there are multiple expressions of that “messiness.”

The legacies of trauma, abuse, sexual assault, normalized violence, colonization, racist domination, and class war wreak havoc on our psychologies, to varying extents. There is no doubt that healing needs to happen (if it isn’t already) at the individual and community level while we work to dismantle oppressive structures and ideologies. But so much of the management of that pain and social harm has been outsourced to a specialized professional class of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who constitute an authoritative, unquestioned “psy-complex.”8 Surely there are effective healers and emotional laborers who find themselves entangled in and navigating the contentious terrain of the professional psy-complex. I know several well-intended social workers and therapists, many of them self-declared radicals, who do good work in either their private practice, or at a halfway house for folks with substance-dependence issues, or doing counseling with foster kids. I have no doubt that these individuals are amazingly helpful to the people they work with. It is not my intention to critique these individuals, but rather to turn my critical gaze towards the psy-complex structure that collaborates with governmental institutions and correctional facilities in ways that complement and enforce formalized systems of control.

The prison system in particular has used psychological evaluations and diagnostic categories of pathology as technologies of power for decades, establishing an obscured “psy”-ence fiction of criminality. In a typical psy-ence fiction, the story understands and talks about the individual sans social context; s/he/they lives in a vacuum and personal change is located in the mind of the individual. These psy-ence fictions try to tell us that criminalized people are those who fall victim to their own delusional mentalities and poor choices, instead of contextualizing criminal behaviors as those that are informed by disadvantage, social exclusion, necessity, and/or survival. Therefore, in any fully realized prison abolitionist or radical agenda, the political strategy must confront the more abstract technologies that control, manage, and subordinate populations. The abolitionist agenda, especially one that espouses anti-oppression intersectionalities, should also concern itself with the host of psy-ence fictions that attempt to regulate prisoners’ mental worlds.

Correctional “Treatment” Regimes

Despite the unplanned nature of Tiana’s crisis, the group understood the need to put our organizing on hold, even though we have just two short hours of every week together, per prison policy. Incarcerated women live through so much unimaginable institutionalized and state-sanctioned violence that it would be difficult for an outsider facilitator to truly practice her emancipatory politics without exploring the personal. We ask Tiana if she wants to share or have us support her in some other way. Tiana wants to talk and she launches into a story about how she was degraded by a jealous “boy-girl” (prison slang for genderqueer or transman) on her way back to her cell. At 6 feet 1 inch, Tiana towers over most others at the prison and has learned to use intimidating body language as a defense mechanism. But that didn’t work in this situation. The jealous boy-girl (X) stepped on Tiana’s toes, called her a “stupid slut,” and head-butted Tiana in her face. Tiana told us that she has not felt so degraded in a long time and, although she wanted to physically retaliate, she has two months left before she makes parole, and so she had to swallow her pride and restrain herself.

I’ve heard Tiana’s story. As she puts it, she’s a “rape baby.” She is a biracial white and Black woman who, when growing up, had a lot of n-words thrown her way but was too light-skinned to fit in with the Black kids. She never felt like she fit in until she started rolling with the “big dog” gangsters. She was repeatedly used and abused by men on the outside. Tiana’s personal history of gendered and racialized violence has sometimes left her silent, sometimes angry, and sometimes apathetic. But I’ve been amazed to see her use her powerful presence in our class to lead activities and to regularly talk about oppression and imagine structural alternatives. As Tiana increasingly steps into and owns her worth, she wants to know how she can transform her rage into political action—both on the inside and on the outside, once she’s released.

Tiana continued to explain her story to the group and said that this confrontation set her back. That she was shaking with an overwhelming sense of being unworthy of anything good or righteous or powerful. Tiana walked away from the brief confrontation and tried to go on with her day as normal, and proceeded with her usual routine of going to the medication line. She saw her partner there, D. She didn’t want to tell D about the incident, but word had already gotten around. Things like that usually make the gossip rounds fairly quickly. D asked Tiana what went down and after Tiana finished her story amidst periodic sobbing, X, the person in question, happened to be walking down the sidewalk toward the med line. Before Tiana could say or do anything, D was in a sprint towards X. D beat X down, badly. D was sent to the hole, and X was sent to the infirmary. Tiana is unsure that she’ll see her boo, D, again before she is released.

As Tiana continued with her story, she laid bare her emotional complexities about the issue. She felt guilty. She thought that maybe if she didn’t cry that hard that D would not have rushed to use physical violence against X. She felt sad. She didn’t want to be released without seeing her primary support person again. And, she felt loved. Tiana said that she was so appreciative to have someone do something like that for her. Tiana said she’s never had anyone “defend her honor” before. Most people in her life were too busy stepping on her to offer any kind of care for her. She also knows that D has never before beat anyone down on a lover’s behalf. Tiana said she feels doubly honored that D, out of all people, would perform this kind of care for her in front of so many people.

At this point, I am itching to talk about the problems with lateral violence—violence enacted towards one’s peers rather than towards the oppressors—and about the need to direct our fury towards the power structure and to treat each other with care. But the other outsiders and I hold our tongues. We don’t interrupt Tiana’s powerful confession of mixed emotions and appreciation for “honor” violence. For the duration of the class, both the insiders and the outsiders support her the best we can. We support each other in that moment, and I know that a conversation about lateral violence might come later, but it can’t interrupt Tiana’s immediate needs or be discussed in the future without also addressing institutional contexts. The prison, as a system and as a structure, is violent. And one would find it difficult to “live” within that system without embodying some aspect of that violence, that is, through developing internalized or externalized hatred, fear, disgust, or anger. Many of the women in our class tell us that they thought (or still think) that they were “crazy” to have angry, explosive reactions, and that they wish they were mentally strong enough to keep their cool in the face of extreme antagonism by other insiders or correctional staff. Most prison and psychiatric officials tell insiders that reacting to violence with violence is a personal choice that can be made or not made. In fact, prison facilities have a multitude of programming that advises prisoners on how to manage their unruliness—and to make “better” and “respectable” choices.

The emergence of the war on drugs and “tough-on-crime” politics of the 1980s and 1990s has, over the course of four decades, led to a globally unprecedented incarceration binge that destroys communities of color and communities living in poverty. This era of mass incarceration has led to an increase in prison and jail populations, while “crime” rates (officially defined) have been decreasing.9 The implementation of mandatory minimums and gender-neutral legislation coalesced to widen the net for women, despite a lack of increase in women’s criminalized activity.10 In just fifteen years, there has been a 400 percent overall increase in women’s incarceration rates compared to a 200 percent increase in men’s incarceration rates during the same time period.11 By way of explanation, feminist historians have tracked the changes to the correctional system’s patriarchal and paternalistic assumptions about femininity, womanhood, and domesticity. The Progressive Era of prison reform, between the mid-1800s and the 1950s, ushered in a peculiar kind of prison facility for women: the reformatory. Despite the variability in prison reformatory models across the US, the common elements included an understanding of women’s criminality as resulting from “madness” instead of “badness,” and having “fallen from grace.” Reformatories predominantly catered to younger white women (reserving for older white women and women of color the traditional prison system), and taught them skills to become more refined, more socially suitable, domesticated women. But, as ideologies about women’s offending began to shift, reformatories became outmoded.

In the crack-cocaine era of anti-Black discourses and politics, drug-using women across racial and ethnic categories became vilified, although to varying extents. The common understanding about women’s criminality transformed into one that emphasized women’s gender, sexual, and parental deviance—although this deviance was amplified in racialized ways. The state’s use of the “welfare queen” and “female junkie” tropes hinged on the imagery of impoverished Black and Brown mothers in the inner city and their children (most commonly depicting shaking, premature infants that were falsely predicted to be a drain and a scourge on society). This narrative served to delegitimize welfare recipients’ worthiness and to also scale back on welfare spending generally. During the same time period that legislators were gutting the welfare “nanny state,” more resources were allocated to building prisons and ramping up the drug war and strengthening sentencing laws for violent crimes. This reconfiguration of the state channeled many women from the welfare system to the prison system. Media reports, official statements, and prison programming emphasized the irrational characteristics of a “new breed” of female deviant, in particular, their “manliness” and departure from the idealized archetype of womanhood. Considering that the net-widening prison system primarily targets women of color, poor women, sex workers, drug users, and single mothers, this understanding that women are not achieving a certain form of womanhood highlights the categorical use of hegemonic (mainstream white middle- and upper-class) femininity in correctional discourses. These racialized, classed, and gendered assumptions legitimate the increased policing and incarceration of women. They also carry over into psychological programming, classifying difference and disadvantage as pathological.

The Personal Is Political; the Personal Can Be Messy; but the Personal Should Not Be Purely Psychologized

The “rehabilitative” and interventionist logics of correctional institutions have absorbed psychological systems of knowledge to construct “normal” people as those who abide by the law and use cool rationality to prevent or think their way out of potentially criminal situations. Therefore any person who might find herself in prison or in trouble with the law falls outside of the morally bound normative category of citizenship. A “good citizen” is one who adheres to laws and who generally aligns herself with ruling ideologies, including the adoption of the myth that citizens can use their psychological powers, such as “determination,” to overcome “perceived” structural obstacles and discrimination. In the context of the prison, cognitive behavioral programs (a model that prisons are increasingly adopting) urge prisoners to learn and adopt rational decision-making skills to avoid criminal thinking and illegal behaviors.12 These programs attempt to normalize or habilitate prisoners and instill a sense of personal responsibility, with the assumption that women take little to no responsibility over their actions, blaming everything and everyone else for their poor choices.

These types of programs also hinge on unstated systems of morality. In traditional prison programming, the cognitive sciences have interestingly commingled with a dated, moralistic approach to changing prisoner populations. In Tiana’s case, a psychiatrist or cognitive behavioral class facilitator presumably would have told her that having relations with another inmate is a violation of the prison rules, and that her involvement with an assault case stemmed from her overt infractions. But moreover, a cognitive behavioral class would have asked: Why did Tiana make the choice to tell D what X did to her? Why wouldn’t Tiana make the better, more “healthy” choice of telling correctional staff that she was threatened and intimidated by another inmate? Why does Tiana feel loved by a violent action? Why has Tiana made other bad choices in her life? Why is Tiana replicating the kind of criminal choices that landed her in prison in the first place? In these questions, the moralistic assumption is that Tiana has the freedom to make any kind of choice she wants to make, instead of understanding Tiana’s agency as bounded by the power structure of the prison setting. The questions also try to imprint upon prisoners that they must ask for assistance from their masters—the correctional staff—rather than settling things among themselves and developing emotional autonomy from the psychological control complex. It is up to her to make the decision between “good” and “bad,” “right” and “wrong,” “legal” and “illegal,” so long as it matches the official definitions. The covert implication of the doctrine of choice is that one can make a decision without the influence of violent institutional contexts, poverty, and histories of trauma, racism, and sexual violence. Yet having more “choices” in a structurally oppressive system typically signifies one’s privileges and advantages within the system.

One of the more peculiar ways that prison programming is becoming liberalized and therefore legitimized is by way of “gender-responsiveness.” Gender-responsiveness is a kind of approach that asserts that prisoners (and ex-prisoners) should receive treatment that takes into account how gender shapes one’s past experiences in terms of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and in terms of one’s involvement in “illegitimate” economies. Prisons adopt gender-responsive models—so far, just in women’s prisons—to claim that their staff and programming take into account the relationship between women’s criminality and histories of trauma. Officials who use this model claim that it provides justice in a partially unjust system; they therefore try to soften the effects of a brutal prison regime for incarcerated women and to appease the critics. These programs use cognitive behavior therapies, described above, along with “empowerment” models, in which correctional staff members teach women how to lead productive lives. The focus in much of these therapeutic programs is on women’s psychological health and how to emotionally overcome their past trauma. Social workers and therapists (and in some cases, correctional officers) assert that the “fix” is less social and more psychological. To the authorities, outside circumstances don’t have to change, but rather, “criminal” women have to stop their “stinkin’ thinkin’,” quit complaining, get more self-esteem, and play by the rules. The psy-complex defines empowerment in purely asocial and individualistic ways, measuring success by quantifying women’s subjective skills like “positive thinking,” and “having a constructive outlook.” Therefore, if a woman has a “negative” attitude, officials believe she is not empowered to lead a future productive life, and she is then scapegoated for the very violence that the prison creates. Historical and structural oppressions become erased and invisibilized by status-quo psychological programming.

Towards a More Liberatory and Politicized Psychology

As prison abolitionists, the other outsiders and I, who have committed to bringing politicized education into the prison, we’re enthusiastic about the idea of building resistance and organizing a movement inside a women’s prison. I was incarcerated in my early twenties and, after my release, radical politics saved my life. It saved me from horribly abusive relationships with my partner (now ex-) and family members, and it saved me from a life of dissecting my psyche and asking the ill-informed question: why was I (and why am I) so messed up? In developing my own analysis of the world and of my life, it’s clear that I acted based on my experiences in a terrorizing system; we all have to navigate an especially hostile world full of exploitation and domination, and sometimes that means some folks, like myself, resort to a syringe full of heroin day in and day out to escape. And since radical politics, particularly anarchism, saved my life, why wouldn’t a structural analysis help folks like Tiana, or others at the women’s prison, who might be struggling with victim blaming and shame?

But it soon became clear that a purely political education doesn’t help with all of the pains that someone struggling with mental health issues has, or that someone who bears the burden of losing her children to the foster care system has. In touting critical analyses as the cure, I must have had a selective memory of what things got me through my time locked down and after my release: friends, music, mutual-aid–based self-help groups like AA, nature, and the structural supports that accompany white privilege. We immediately felt the disconnect between what the outsiders wanted—wanting to talk about organizing and the connection between heteropatriarchy, white supremacy and domestic violence—and what the insiders wanted: to never be in an abusive relationship again (and in some cases, to get out of the abusive relationship they are currently in); to relieve the suffering of prison life; and to better connect with family and supporters on the outside. We failed to recognize or remember the immediacy of many of the needs in the room, which prompted a collective reflection, including on the part of insiders, on how we might build a class together that can achieve a better union of the personal and the political.

Ignacio Martín-Baró, a Jesuit priest, scholar, and activist assassinated by the Salvadoran army in 1989 for his anti-authoritarian views and his scholarship on liberation, argued that the sociopolitical and the individual are inseparable. Moreover, he argues that any psychological endeavor must move beyond the personal and incorporate a community-and structural-level analysis. Inspired by Paulo Freire and the conceptual development of oppression in South and Central America during the 1960s and 1970s, Martín-Baró contended that developing a critical consciousness, or concientización, of how power and oppression operate to suppress dissent and total freedom was a necessary step in liberation. He writes that the “awakening of critical consciousness joins the psychological dimension of personal consciousness with its social and political dimension,”13 and further argues that understanding the personal would be “incomprehensible” if the social structural reference points were omitted. Therefore, avoiding discussions of the psychological effects of oppression can lead to alienation; personal experiences should be considered a necessary part of organizing relevant political projects.

Healing from the psychological wounds that are inflicted by daily acts of violence, microaggressions, and systematic degradations demands that we critically understand power structures and work to transform them. The cycle of liberation is one that incorporates the personal, the community, and the social, and honors the interconnectedness between them. “Recovering the historical memory”14 and reclaiming cultures are necessary projects for providing psychological support and political momentum, yet mainstream psychologists (and other “experts” for that matter) have ignored these needs. This violent ignorance (and at times blatant suppression) arises when psychologists are incorporated into the “professional” stratum in which they hold positions of power or work for powerful authority figures, instead of working for the people they claim to serve. The psy-complex experts are not interested in directing attention to much outside of the patient’s mind because, to psychologists, we cannot control the outside world; we can only control our reactions and our perspectives.

A radical political analysis should not only directly refute this individualistic take on social problems, but it should also prioritize the needs, desires, and interests of the group or set of individuals seeking psychological healing. For oppressed and exploited peoples who are subject to monitoring and psychological evaluation through the prison system, I contend that developing networks of mutual aid and support are more empowering than outsourcing our psychological grievances to specialized experts. In our prison class for survivors of intimate partner violence, we focus on a cycle of liberation that includes specific strategies to heal the personal, nurture the intrapersonal, and engage with the political. In personal terms, we nourish our psyches by validating each other’s feelings, encouraging self-exploration in terms of sexuality and identity supporting self-care, and promoting artistic expression. We recognize the valuable qualities of courage and resiliency that women already hold in the room.

In finding liberatory possibilities on the intrapersonal level, working within a prison setting can be especially difficult and challenging. Violent institutions breed resistance, but they also sometimes breed hostility, backstabbing, horizontal divisions, and gossiping among people who are similarly oppressed. In our class, this means that there is an initial growing period in which new participants who might have been unfriendly with each other join the outsiders and the more experienced insiders in finding our common struggles and our empathy for the struggles we have not experienced. This solidarity-building is especially effective in exploring the controlling dynamics of the prison administration and how each person experiences this power regime. We sometimes do this by using Theatre of the Oppressed activities in which participants can role-play oppressive dynamics that they may have experienced or witnessed and brainstorm how, if at all, the oppressive “character” can be undermined or resisted. In developing a sense of community with each other, we also better nurture individual expressions and feed our psychological needs. Using improvisational body movements and writing poetry or essays often helps to facilitate different ways to use voice. And, if the personal and the intrapersonal reveal existing commonalities, discussing the political becomes an exciting exploration of strategies for action and organizing.

In assessing our personal-is-political projects, especially in a women’s prison, we must broaden our ideas of what is political, so as to also understand how acts of resistance are wide-ranging and not simply reducible to a prison riot or hunger strike. Victoria Law has produced great documentation of how we can think about and classify resistance in women’s prisons.15 A behavior is political when it confronts oppression and supports class and group interests, meaning that refusing to stay silent, filing grievances, and supporting each other are all political acts. When Tiana, for example, asks for emotional solace and a dozen women on the inside put their organizing projects on hold to cry and laugh with her and tell her that she is loved despite the messiness of the situation, the act is a political one.

Colleen Hackett (firehawk) is an ex-con, writer, educator, and organizer. With a few unruly outsiders and many exuberant insiders, she cofounded Webs of Support, a prison program led by incarcerated women who have experienced intimate partner violence. She’s also involved in a new antiauthoritarian prisoner publication, Unstoppable!, which is by and for prisoners who identify as women, gendervariant, or trans (unstoppable.noblogs.org). She lives with her dog in the desert and enjoys tae bo, bicycling, and deep-eco-pagan-metal.

NOTES

- The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report.

- Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press, 1982).

- Lisa Marie Cacho, Social Death: Racialized Rightlessness and the Criminalization of the Unprotected (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2012).

- Sandra Harding, Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?: Thinking From Women’s Lives (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), 171.

- Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000).

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007).

- ibid, 114.

- Shoshanna Pollack, “Taming the Shrew: Regulating Prisoners through Women-Centered Mental Health Programming” in Critical Criminology, 2005 13: 71-87.

- The Sentencing Project.

- Jill McCorkel, Breaking Women: Gender, Race, and the New Politics of Imprisonment (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2013).

- The Sentencing Project.

- Kelley Hannah-Moffat, “Criminogenic Need and the Transformative Risk Subject: Hybridizations of Risk/Need in Penality” in Punishment and Society, 2004 7(1):29-51.

- Ignacio Martín-Baró, Writings for a Liberation Psychology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 18.

- Ibid.

- Victoria Law, Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012).

The views expressed herein solely belong to the author(s) and are not necessarily representative of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, the Institute for Anarchist Studies, or members of its Board of Directors.