This book review appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29) available from AK Press here!

This book review appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory (N. 29) available from AK Press here!

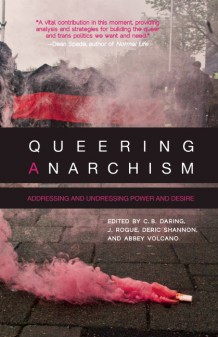

Queering Anarchism. The title suggests a process, something in motion, developing, unfolding, undefined, unsettled. Indeterminacy is part of the point of the subversion of categories, an opening of possibilities, simultaneously emphasizing and easing difference. What was once hidden becomes apparent; what was once obvious becomes absurd. Both the anarchic and the queer challenge the status quo. Both expand our sense of the possible, enlarge our idea of freedom. What happens when these two mercurial concepts come into contact?

In making the attempt, Queering Anarchism accomplishes something remarkable, providing a good, quick orientation to anarchism and a short introduction to queer politics and queer theory. And by relating the two, it enacts a kind of intervention into each. The book’s twenty-one chapters show that queer politics needs an analysis of class and power, and that the anarchist critique of capitalism and the state has much to gain by incorporating questions of gender and sexuality. The contributors consider the multiple ways that power relations shape our sex lives, our gender expressions, our family arrangements, our sense of self and belonging, and even our desires, fantasies, and entertainment. Conversely, they also explore the ways that freedom might change those things and moreover, how changing them might in turn transform our understanding of freedom. As Jerimarie Liesegang writes in “Tyranny of the State and Trans Liberation”:

Whereas anarchists and anarchist theory need to look at struggle on the conceptual level that queer theory provides, queer theory needs to be coupled with anarchism’s critique of structural domination, such as the state and capitalism. (96)

If that sounds a bit like a dare, it is a dare worth taking.

But dares do not always succeed. Many of the contributors indulge in some unwarranted leaps of logic, and more (perhaps most) suffer from an excess of optimism about their own intellectual and political projects suggesting, for instance, as Liesegang does in that same essay, that queers are “truly inherently revolutionary peoples” (96). The result is an intellectual recklessness and occasional obsession with the first person singular, which sometimes manages to be charming but is equally likely to annoy. One of the longest essays in the book, provocatively titled “queering heterosexuality,” amounts to little more than a strangely unrevealing all-lower-case rumination on the author’s emotional growth. Another writer, likewise lacking any sense of self-effacing irony, settles into the view that “the most radical thing I do is meditate daily” (73). This is partly the result of looking through the wrong end of the “personal is political” telescope, but sometimes it is just a matter of getting carried away by an exciting idea, exaggerating its significance and swelling our expectations. Luckily, other contributors recognize the risks and, while pressing a radical analysis as far as it can go, also skillfully flirt with the ridiculous as captured in the book’s closing line: “And everybody gets a unicorn” (236).

In general, prose in Queering Anarchism is pleasant and engaging, and remarkably free of the Foucault/Butler aesthetic of opacity. So readers will notice that the various authors do not always agree. Definitions of queer, approaches to anarchism, political strategies, philosophical traditions, and styles of argument all vary within the volume. That is, of course, all to the good. And those divergences, arguments, and contradictions only make more notable the themes that recur across multiple chapters. Among these are warnings against inverting (rather than dismantling) hierarchies, the view that “queer” is not an identity but a refusal of identities, and the insistence that no matter how you dress, or with whom you sleep, “queer liberation is for everyone” (226).

More than anything else, Queering Anarchism is a refreshing read. It is, on the whole, thoughtful but not obscure; challenging but never hectoring; and substantive as well as fabulous.

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, Hurt: Notes on Torture in a Modern Democracy, and Fire the Cops! He is a member of the Perspectives’ collective and the Institute for Anarchist Studies. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

The views expressed herein solely belong to the author(s) and are not necessarily representative of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, the Institute for Anarchist Studies, or members of its Board of Directors.