This essay appears in the current issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, N. 28, on the topic of Justice. The full issue is available from AK Press here!

Since the publication of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness in 2012, there has been much talk about the need to end mass incarceration. More and more people are speaking publicly about the moral and financial implications of maintaining the world’s largest prison system. However, what it means to end mass incarceration, and what it would take to end it, is less clear.

Mass incarceration plays a central role in maintaining state and capitalist power in the United States, and abolishing the prison system must play a central role in movements for radical change. Mass incarceration allows the state to perpetuate unpopular economic policies that would not be possible in the face of strong resistance movements. While reform efforts might cause the structures of mass incarceration to shift, and lead to decreases in the prison population (as is already happening in some places), a more fundamental transformation is necessary if we hope to see an actual rather than cosmetic shift in the meaning and practice of “justice.”

Our efforts to end mass incarceration cannot be rooted in reform, but must instead address the structural roots that have given rise to the world’s largest prison system. We must create movements that thrive on our differences and build on our strengths. The prison system sits at the nexus of multiple forms of oppression, so we must generate analysis and resistance that is intersectional. Supporting political prisoners, developing the capacity to withstand state repression, and embracing meaningful forms of justice and healing, horizontal models of sharing power, and feminist and queer ways of understanding the multitude of possible futures are all part of this struggle.

Walidah Imarisha launches Angels with Dirty Faces in Portland!

Great turnout at Portland, Oregon’s Powell’s Books for the launch of Angels with Dirty Faces, new from the Institute for Anarchist Studies and AK Press. Get a copy here from AK!

With these stunning contradictions in mind, and with all legal options exhausted, local people and climate justice rebels took matters into their own hands in the summer of 2014 by establishing a resistance camp on the mine lease in order to halt mining operations. Amidst a summer of blockades, police repression, and the stresses of day-to-day rural resistance, it’s been a challenge to maintain a global perspective. It’s clear that our fight is being driven by capital and technical knowledge generated through the exploitation of the Alberta tar sands. It’s also clear that there are financiers intending to export these mining operations around the world using

With these stunning contradictions in mind, and with all legal options exhausted, local people and climate justice rebels took matters into their own hands in the summer of 2014 by establishing a resistance camp on the mine lease in order to halt mining operations. Amidst a summer of blockades, police repression, and the stresses of day-to-day rural resistance, it’s been a challenge to maintain a global perspective. It’s clear that our fight is being driven by capital and technical knowledge generated through the exploitation of the Alberta tar sands. It’s also clear that there are financiers intending to export these mining operations around the world using

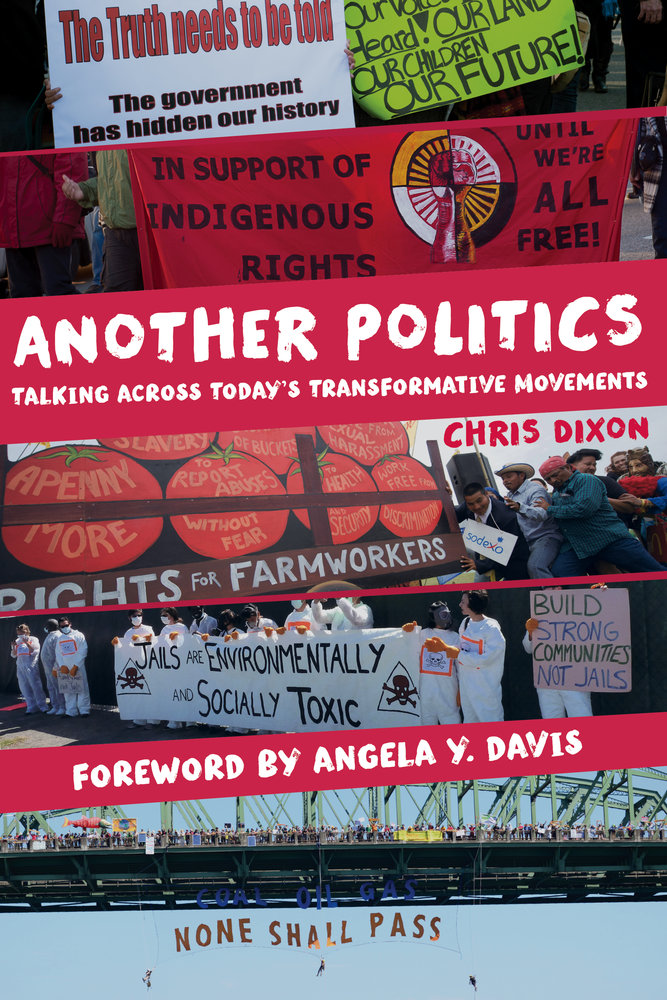

It was in that discussion that I first became aware of what Chris Dixon (2014) explains, in his book Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements, is a fundamental principle underlying the antiauthoritarian current in today’s social movements: we were trying to figure out how to work “in the space between our transformative aspirations and actually existing social realties” (8). We saw in those campaigns two very different yet interconnected desires – the prefigurative aspirations of a world where people had the freedom to move and the freedom to stay, and the struggle to dismantle the state, capitalism, and the white supremacist settler colonial logics that undergird Canada’s immigration laws.

It was in that discussion that I first became aware of what Chris Dixon (2014) explains, in his book Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements, is a fundamental principle underlying the antiauthoritarian current in today’s social movements: we were trying to figure out how to work “in the space between our transformative aspirations and actually existing social realties” (8). We saw in those campaigns two very different yet interconnected desires – the prefigurative aspirations of a world where people had the freedom to move and the freedom to stay, and the struggle to dismantle the state, capitalism, and the white supremacist settler colonial logics that undergird Canada’s immigration laws.