This review of Chris Dixon’s Another Politics appears in the current issue of Perspectives, available here from AK Press.

It was one of those meetings where the room we booked was far too large for the number of people who actually showed up. It was the type of meeting where you rearrange the chairs to form a small circle in a corner so that the disappointing turnout feels less deflating. Myself and three other members of No One Is Illegal-Toronto huddled to discuss two fledgling campaigns we were involved in. The first was the awkwardly named “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”1 campaign that hoped to mobilize toward a municipal policy that would bar city staff from asking for immigration identification or reporting someone’s immigration status to the authorities. The second was our anti-deportation direct action casework, which evolved from a model developed by the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty to fight welfare bureaucracy. We had faced a soul-sucking defeat earlier that year following the deportation of beloved community activist Queen Nzinga, who was arrested by Toronto police at a bake sale during International Women’s Day. It was mid-summer 2005, and the day-to-day grind of organizing had taken its toll on our collective energies. Without the bulk of the group’s members, we decided to not have any discussions about nuts and bolts of organizing upcoming events or actions and instead have a more general conversation about the direction of our collective.  It was in that discussion that I first became aware of what Chris Dixon (2014) explains, in his book Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements, is a fundamental principle underlying the antiauthoritarian current in today’s social movements: we were trying to figure out how to work “in the space between our transformative aspirations and actually existing social realties” (8). We saw in those campaigns two very different yet interconnected desires – the prefigurative aspirations of a world where people had the freedom to move and the freedom to stay, and the struggle to dismantle the state, capitalism, and the white supremacist settler colonial logics that undergird Canada’s immigration laws.

It was in that discussion that I first became aware of what Chris Dixon (2014) explains, in his book Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements, is a fundamental principle underlying the antiauthoritarian current in today’s social movements: we were trying to figure out how to work “in the space between our transformative aspirations and actually existing social realties” (8). We saw in those campaigns two very different yet interconnected desires – the prefigurative aspirations of a world where people had the freedom to move and the freedom to stay, and the struggle to dismantle the state, capitalism, and the white supremacist settler colonial logics that undergird Canada’s immigration laws.

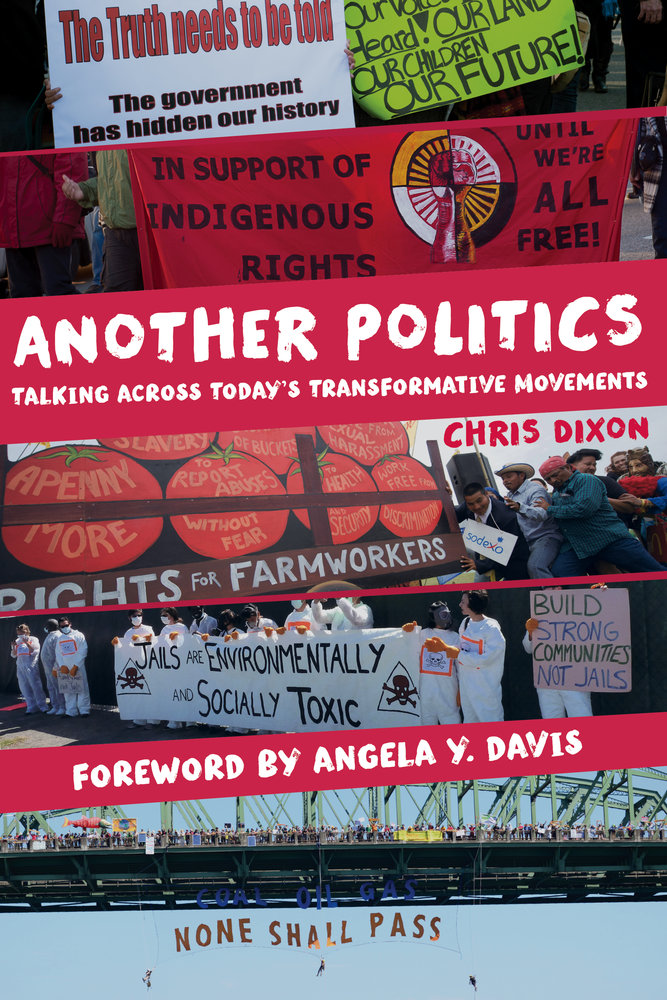

In Another Politics, Dixon takes on the important task of collecting these bits and fragments of transformative conversations within what he convincingly identifies as “the anti-authoritarian current” of radical social movements in the Canadian and U.S. settler states. Dixon helps to facilitate a broader dialogue on our histories, politics, strategies, and forms of organizing. Unique for a book based on in-depth interviews, Another Politics is written in a way that actually feels like a conversation between the forty-seven organizers Dixon interviews in Montreal, New Orleans, Atlanta, New York City, the San Francisco Bay Area, Toronto, and Vancouver. Instead of using the knowledge shared by interview participants to help elucidate his theories, what emerges are robust and relevant conversations between antiauthoritarian radicals on the roots and nature of our movements. Dixon, himself, plays the role of the self-aware facilitator chairing a virtual meeting based on the principles of “noninstrumentalist organizing” that aims “to build relationships with people as collaborators in struggle rather than as instruments to achieve already determined ends” (167). Drawing from experience gained as an active participant in these movements, Dixon’s Another Politics attempts to reimagine the act of writing political theory through the principles being developed within the antiauthoritarian current, including: writing from the ground-up; linking struggles of resistance with our long-term transformative visions; and developing new ways of being that center the collective process of knowledge production over the individualism inherent in a project such as writing a book.

The text is divided into three parts: politics, strategy, organizing. In the first section, Dixon draws from his interviews to historically situate what he dubs the “anti-authoritarian current” (a name he admits is not readily agreed upon by everyone associated with these politics) within four core trajectories: women of color anti-racist feminism, prison abolitionism, contemporary anarchism, and anti-colonial struggles. The participants in the book set out to identify some shared principles across differences. Dixon acknowledges that this process is experimental, uneven, and messy—and yet—the wide range of connected efforts that “blend our political aspirations with practical organizing methods” (166) has produced a shared understanding of this emerging politics.

Similarly, the struggles to contextualize our campaigns in No One Is Illegal-Toronto back in 2005, resonated with the multiple discussions highlighted by Another Politics as being rooted in a desire to balance the need to “define ourselves in opposition” (what Dixon lists as the four antis: anti-oppression, anti-authoritarianism, anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism) and to “organize now the way you want to see the world later.” Importantly, the book brings forward an important differentiation between this “antiauthoritarian” current and other Left political struggles in that it tries to “stay critical, avoid dogmatism, and actually find what works” (59). Eschewing “correct-line” politics for a more fluid and collaborative approach, Dixon argues that those who organize within the antiauthoritarian current incorporate a humility and openness to being challenged that breaks from the rigid and sometimes formulaic politics of other Left political projects. Giving credit to the influence of women of color anti-racist feminists, he describes how a number of the interview participants explained this shift as being related to adopting a politics of care or a politics of simply being nice. Others, such as “Harjit Singh Gill, an Oakland-based social worker and board member of the Institute for Anarchist Studies, called it ‘not being a fucking asshole’” (92). While acknowledging the importance of this politics of care, the organizers Dixon interviews also explain the importance of building resistance and prefigurative spaces towards a confrontation with the state and capital. This is an important contribution to the discussion that often gets gleaned over by those dogmatically aligned to pacifism or strategies of “non-violence” and one that clearly expresses the role of mass-based organizing as a core part of the struggle.

That being said, Another Politics, in my opinion, does not delve deeply enough into the challenges faced by organizers in these movements to successfully combine prefigurative practices and confrontational politics in a broad and mass-based way. That’s not to say that Dixon glances over the shortcomings of antiauthoritarian movements over the past twenty years, but simply that at times the book favors an optimistic and hopeful reading of the trajectory of our movements rather than confronting the political realities that have forced our movements into often reactionary positions. As reviews of the book by both Justin Podur and Gary Kinsmen point out, Another Politics could have been strengthened through an exploration of the ways in which antiauthoritarian movements have struggled to confront the expansion of neoliberalism through global austerity and the rise of neofascism and xenophobia throughout the West. Dixon does, however, engage significantly with key factors hampering the mass appeal of ‘another politics’ to building counter-power (the nonprofit industrial complex, unwelcoming subcultural scenes, the tendencies toward spreading ourselves too thin and so forth).

Additionally, some key fractures and important questions facing the antiauthoritarian current are noticeably absent from the core analysis of Another Politics. For example, Dixon introduces the context of settler colonialism as important in situating the emergence of the antiauthoritarian current within Canada and the United States. He asks “What would it mean for the inhabitants of this continent, both Indigenous and settlers, to overcome colonial relations?” (79) suggesting that the willingness of those associated with the antiauthoritarian current to leap into the messiness of questions such as these is a defining feature of the anti-imperialist/anti-colonialist politics being developed within ‘another politics’. However, the prefigurative aspirations of Another Politics often fails to situate what liberation and counter-power look like within a context of settler colonialism, an issue that has confronted the antiauthoritarian current within migrant justice, anti-capitalist, anti-racist movements and most notably the various Occupy Together actions.

With these critiques in mind, I think Another Politics contributes important lessons for anarchist theory by delving into the experiences of grassroots organizers engaged in practices of antiauthoritarianism. For instance, Dixon highlights the desire of those practicing ‘another politics’ to veer away from creating insular, sub-cultural scenes that may be prefigurative in their intent but lack the type of mass-building necessary to create tangible confrontation with state-based society. The tendency of both dogmatic and intellectual anarchist traditions to embrace and cling on to the distinction of thinking and living outside of the dominant logics of domination is challenged by the emerging antiauthoritarian movements who seek to transcend these limits by “being in the world, but not of it” (126). For this to happen, organizers need to understand the terrain of struggle in which they are mobilizing and to collaborate and build alliances with broader grassroots communities without necessarily abandoning antiauthoritarian principles. To do so, Dixon’s participants highlight the importance of humility, decolonization, the challenging of patriarchal relations, and the recognition of the ways in which we take on leadership responsibilities. A number of participants in the study reject the “no leadership” discourse that has been prevalent in movements such as Occupy and instead articulate how “people often gravitate into leadership roles because of important qualities that they have to offer, such as experience, skills, knowledge, initiative, connection, and dedication” (180). Through difficult experiences resulting in conflict, internal power struggles, and sometimes the dissolution of collectives, these organizers offer a nuanced and complex understanding of leadership that understands the multiple ways in which we come into radical movements, the skillsets we bring, the mentoring we undertake, and the structures of accountability that we create to acknowledge and practice forms of leadership.

Another Politics forced me to reflect on my own experiences in migrant justice, anti-colonial, queer, and anti-capitalist organizing in Toronto over the past decade. With a number of familiar names and groups, I immediately felt an affinity with the overarching questions and themes of the book. So it was no surprise that I sought to position my own experiences in groups like No One Is Illegal-Toronto in relationship with the book’s content. As I drifted in and out of recalling these memories, the usefulness of Dixon’s contribution to our struggles in the form of Another Politics became evident. I was able to identify the ways in which No One Is Illegal-Toronto’s two major campaigns evolved and shifted to articulate the power of the “against and beyond” that Dixon asserts is central to another politics. I could relate significantly to our struggles to balance our principles over our plans or our tendency to fetishize particular tactics—only to find out that different times and different circumstances warrant different approaches—something that is not always apparent in the day-to-day grind of movement building. If something works, it’s often easier to stick with it, but as Dixon offers, “One of the most troubling outcomes of this is that, as activists and organizers, we end up focusing most of our attention on debating the validity of certain tactics rather than on considering how those tactics fit into overall plans to achieve something.” (113)

In No One Is Illegal-Toronto we have also struggled with what participants in Dixon’s interviews describes as “crisis-mode” organizing. I could relate on both a personal and a group level to the kind of burnout and disillusion this form of movement building can create. There are no shortage of injustices and attacks on migrants, racialized peoples, Indigenous peoples, disabled peoples, queers/trans folks and all other peoples particularly attacked by Canada’s immigration and colonial policies. Yet, as Dixon reminds us, “While acknowledging the crises around us, then, we have to allow ourselves to pause, reflect, and become more intentional and visionary. We need strategy” (115). I think it was this shift to long-term strategies that helped our collective achieve significant victories and develop a broad based appeal amongst migrant communities and allies in and around Toronto. These reflections would lend themselves greatly to structuring workshops, internal dynamics meetings, and strategic planning within the broader antiauthoritarian current.

In this sense, Another Politics is a useful contribution to both long time activists and organizers and those who are newly engaging in antiauthoritarian politics. It is also a vital challenge, through mainly experiential knowledge, to the party-building, nonprofit, and other absolutist political doctrines that are prevalent on the Left. The book is also a self-reflection and critique of the potential barriers and contradictions we face within the antiauthoritarian current including the ways in which we continue to struggle with oppressive power dynamics within our groups, the limited models or memories of practicing another politics, and the political reality that while growing in strength our movements remain far from being an effective counter-power to creating revolutionary change. Dixon, playing the important role of optimist in narrating the stories of our struggles, concludes the book by trying to push those of us in the antiauthoritarian current to imagine our struggles outside of what we know. In this sense, he is not articulating some grand utopian vision of society, but rather is suggesting that we push ourselves to believe in the possibility of making our movements resonate far more broadly within our society. Here he notes, “One helpful answer [San Francisco-based organizer David Solnit] offered is developing ‘humble continuity’—a practice of carrying lessons and challenges between movements. This he said, ‘requires some gracefulness of those of us…who’ve been around for a while to figure out how to work with newer activists—and do it gracefully—where you’re not dictating, you’re respecting, you’re leaving space for innovation” (230). In a sense, Dixon’s book attempt to practice these very principles by helping to guide us through some of the important challenges faced by our movements, but never closing the space for innovation and the radical imagination to flourish.

Notes

1 The Don’t Ask Don’t Tell Campaign was launched by No One Is Illegal-Toronto in 2004. Currently in Toronto, city residents without full legal status face significant barriers to accessing essential city services, such as emergency services, housing, food banks, health care, and education. These barriers exacerbate and perpetuate the fears of detention and deportation that thousands of city residents are forced to live with. A Don’t Ask Don’t Tell Policy would make city services available to all residents, regardless of their immigration status. The policy would ensure that all city residents, including people without full immigration status, can access essential services without fear of being detained or deported. In 2013, Toronto became the first city in Canada to be declared a “Sanctuary City” thanks to the decade long struggle by No One Is Illegal-Toronto and allied groups. The struggle for a broader solidarity city continues and you can follow it here: http://solidaritycity.net.

Craig Fortier has participated in migrant justice, anti-colonial, queer, and anti-capitalist movements for over a decade in Toronto, Canada (Three Fires Confederacy, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wyandot territories). He is currently completing a dissertation in Sociology at York University, studying how radical antiauthoritarian movements learn, imagine, and practice processes of decolonization.