Since Trump’s election, fascism has barged onto center stage, moving more brazenly into public space, mainstream media and public discourse than it has in decades. This renewed and emboldened presence of overt fascism has been met by an explosion of analysis and discussion about its history and politics, and the conditions necessary for its emergence. A proportionally growing attention is also being paid to the history and politics of anti-fascism.

This is welcome, and it is crucially needed. However, it’s also true that the bulk of the writing and speaking on fascism and anti-fascism—the better-selling books, the high-profile interviews–are being done by white men.

Meanwhile, women, queer and trans and communities of color, particularly Black and Indigenous communities, have been experiencing related forms of violence and raw hate for years with full cognizance of the implications. Yet their analysis and resistance has not been accorded the same urgency and attention—even keeping in mind the major tectonic shifts initiated by the Black Lives Matter and No DAPL anti-fossil-fuel pipeline movements, for instance.

(You know, like when a liberal sees something happening and is shocked, SHOCKED! While an anarchist just nods grimly and says “Yeah, that’s what we’ve been telling you this whole time.” It’s often that way with the perspectives of cis-white-male and not-cis-white-male points-of-view too.)

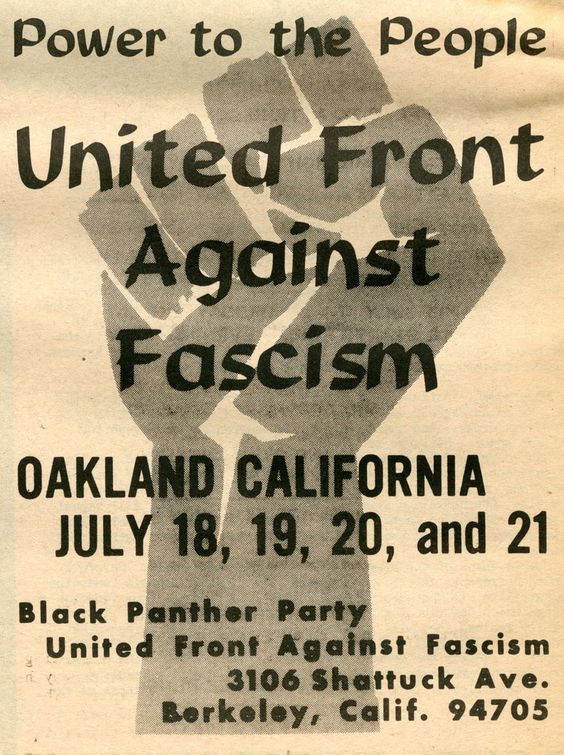

When the first great global anti-fascist Popular Front emerged in the 1930s, Pan-Africanists and Asian anti-colonialists pointed out to their white leftist comrades and allies that what appeared unprecedented and alarming to them when it reared its head in Europe was already long-familiar to those on the wrong side of the color line. The logics of white supremacy, its institutions and systematized practices, the brutal dehumanization (racialization, criminalization) of the “Other,” the violent misogyny, had all been routine components of the apparatus of colonization, conquest, and dispossession. Those logics, rhetorics and practices had merely continued along their obvious trajectories by blossoming into fascism at home, where the shock was that they appeared close by and visited upon “us” rather than far away and visited upon “them.”

Black and brown revolutionaries declared (and proved) themselves ready and eager to step up and join the fight against fascism, while also insisting that these connections not be overlooked; that Hitler, Mussolini and Franco could not be confronted without simultaneously dismantling the British and French empires and the US racial regime, or the whole enterprise would be fatally flawed. Maybe what we’re seeing now shows that they were right.

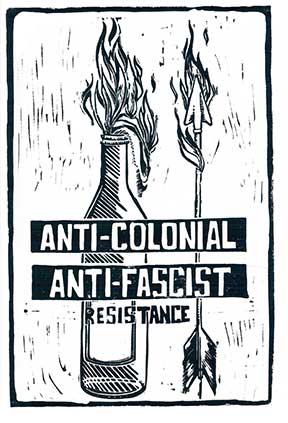

So what about now? What comparable connections need to be stated and foregrounded?

We need analysis and historical contextualization of fascism and anti-fascism, but we also need analysis and historical contextualization of its relationship to longstanding anti-racist resistance and decolonization efforts. We need to talk about how institutionalized forms of white supremacy connect to the racism and imperialism of US world interventions. We need to understand what’s different and distinct about the present moment, while also understanding its intersections and continuities, in order to provide fuller perspective and therefore a more effective ability to fight back.

And for that, we need to be hearing from more people than just white men, who may sometimes miss some of these connections, or may feel unauthorized or unequipped to address them. We need to be hearing more from those who have never stopped experiencing, recognizing, calling out and fighting back against the not-so-dormant forces which have produced this latest crop of malevolent blossoms.

We appreciate those who have laid out their analyses; they are essential to our struggle. And we also need to hear from the rest of the comrades, organizers, writers, and everyday folks. This is happening, and we want to amplify it. (For example, check out the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Dilar Dirik, William C. Anderson and Zoe Samudzi, Robyn Spencer, Upping the Anti collective, among others.)

If you are writing, talking, and speaking out publicly, and if you want another forum for what you have to say, write us at: PerspectivesonAnarchistTheory@gmail.com. Whether you only have an idea, or a rough draft that needs work, or a fully formed and polished piece, we’d like to see what you’re thinking and consider it for publication.

~ The Perspectives on Anarchist Theory collective, of the Institute for Anarchist Studies

3 thoughts on “Beyond Anti-fascism, But Not Without It”

Comments are closed.

Nice piece! Regarding, “When the first great global anti-fascist Popular Front emerged in the 1930s, Pan-Africanists and Asian anti-colonialists pointed out to their white leftist comrades and allies that what appeared unprecedented and alarming to them when it reared its head in Europe was already long-familiar to those on the wrong side of the color line.” Any good citations for this? It’s a topic I’d like to read more about.

Reblogged this on Rage Against Capital.

Ho Chi Minh, Maurice Bishop, and Sankara the closest we get to successful decolonial revolution. Ho Chi Minh is a great start because he is the earliest. He also used to chill with Marcus Garvey back in the day.

It sucks that so many white radicals become chauvinists once they lose their position as Main Protagonist and take a back seat on the right side of history. I think it has to do with fear of reprisal, or fear that we turn them into subhumams on an ontological basis.

Whatever the reason is, I hope they begin to acknowledge the caste system of global white supremacy that has culminated over the years of various oppressions, so deep to even reach the spheres of art (see casta paintings on wikipedia).

Non-Blacks did it first when they cultivated the Zanj Rebellion and genocide in the Congo at the hands of Leopold of Belgium. But of course no one wants to address these topics… One can only hope this changes in the future :(.