Prison creates a different picture in the minds of those who have been there and those who send people there. We are indoctrinated to believe the prison system was created to keep our friends and neighbors safe. That prisons exist to help rehabilitate those criminals deemed fit for rehabilitation and keep those judged unfit stowed away from the public. My memories of prison are of being forced to stand barefoot on the sidewalk in August, when the word “hot” is not strong enough. Blood actively ran down my wrists from open wounds after a suicide attempt. The officer transporting me to the hospital told me that since I wanted to die, I wouldn’t mind the pain of the hot pavement. I was not allowed to step on the grass.

There is a gap between what the state says we have prisons for and what actually happens behind their walls. We can begin to overcome this gap when those of us who have been incarcerated start to discuss our experiences freely. Without this, the state’s perspective is the only one widely seen concerning the effects of incarceration. But why do we so infrequently hear the stories of those who have been, and still are, behind the walls of the American prison system?

Most people don’t want to talk about their time in prison. Some are still confined within the legal system and feel the need to comply while on probation or parole, and therefore feel more afraid about speaking out. After being locked away for any length of time, the majority of those released will do what they can not to return, and often that means not talking about any of the trauma they experienced. I have personally felt that speaking out would draw attention to myself, to my felon-status, and even cause possible incrimination. I believe that this is a goal of the criminal legal system—to keep us quiet. To keep us from speaking aloud the things we will never forget.

The prison system teaches us to be silent and to create personal guilt to justify anything that happens to us while incarcerated. There is an “I deserve this” mentality and a “I just want to forget about this” frame of mind, which go hand-in-hand. This is understandable, but it is also detrimental to the abolitionist movement because the people who are most capable of speaking directly about the horrors of the prison system are oftentimes the ones who want so little to do with it. We spend our time trying to survive and navigate our own guilt and pain while incarcerated; it is hard to see beyond that personal torment. Even if you do not feel guilt, your anger can be so overwhelming that the injustice of the situation seems to have no solution. There is no way to right the wrongs that have happened to you.

These are two sides of the same coin. We are in fear of our anger because we either feel we deserve the treatment, and therefore should not be angry, or we feel there is no way out of our anger, and that there is no way to dismantle the system that has confined us. Either way, when we cannot express it, we come to believe that our anger will only hurt us. Every ounce of anger felt in prison can feel so fake, so selfish, which is hurtful, because prison does hurt, it does maim, and it does kill those inside its walls. But admitting that is a monumental task. Our will to survive may be all that we have. We create prisons within our own minds in the hopes that they will keep us safe. We believe that this is strenght, or dignity, but it is in fact exactly what those who imprison us want. The mindset of silence is passed down from warden to officer and then from inmate to inmate, generation to generation. When trouble arises on the prison floor officers order you to turn around and face the wall. You see nothing, and therefore you say nothing either. If you speak, officers label you as an accomplice. Speaking out against violence, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, or any type of dehumanizing action carried out by officers and other prison staff is met with retaliation and isolation. Inmates who speak up are often “put on lock” and denied the freedom to leave their cells for meals, showers, and even basic medical services. So we become silent. Inmates teach other inmates these safety tips and the silence becomes inculcated.

There are few other options for inmates who are trying to keep themselves safe and make a good impression to the parole board. As inmates we receive favor through our compliance, even when we are complying with state-sanctioned violence and harm at the hands of guards within the prison walls. Guards and prison employees will tell us that we deserve any manner of treatment that they decide, and over time you begin to believe them. So we retreat, and tell our fellow inmates to retreat as well, believing that if we are quiet enough for long enough, we will be granted freedom and solace from the pain of incarceration.

Fearing our own anger—fearing ourselves—we inmates decline into silence, a process intensified by the severe stress that inmates suffer continuously during incarceration. For instance, in one week I saw women have their hands smashed in steel doors by correctional officers, washed the blood of a friend off my cell floor after she was brutally attacked with an officer’s walkie-talkie for accidentally bumping into them, and was myself locked in a closet by an officer who just wanted me to beg to be let out.

We process the trauma and stress with silence. Ignoring, retreating, and packing things away is a habit that follows many of us home, where we never fully process our time behind bars, and are therefore never ready to speak out about the crimes committed against us. I had detached myself from the traumas of incarcerations and, once home, I just carried on, instead of spending the time to heal myself and verbalize my experience. It has created a huge discord and lack of connection with many people who I used to be close with. My family has little idea of the things I saw and experienced. This is the case for many other women I have talked to. We push things down in an attempt to have a sense of normalcy in our lives again, only to lose the chance for understanding and compassion from others.

This trend is not only detrimental to our lives during and after incarceration, but it also is a huge gap within the abolition community. How do we promote abolition within the walls of the prison system? How do we do so in a manner that not only keeps former and current inmates safe, but also helps them process the crimes committed against them, and at the same time, helps them fight for their families and neighbors who are just as affected by this system as they are?

Whose voices do we hear when we discuss the prison system? Those locked away cannot speak, and those freed are so scared to speak that our voices are never heard: stories vanish behind the walls that imprison them. This is a waste, because it is the prisoners’ stories that have the greatest potential to bring about change. Transforming fear into strength would not only help those who are incarcerated speak out against the inhumane conditions of the prison system but could also help initiate ideas of a transformative justice within our communities.

As a ward of the state, I was tught to hide behind my own guilt, to hide behind my fear. Officers, in particular, were skilled at researching inmates and belittling them with information specific to their crimes. If you don’t say anything, chances are you’ll stay safe from any physical violence or receiving a write up that could affect your parole eligibility. I stayed quiet when I was scared because it seemed like the safest thing to do. I stayed quiet because I felt I deserved the horrors happening to me and didn’t have the strength to think beyond that. The officers and other employees tell you from the beginning that if you are quiet, you won’t have any problems. But this wasn’t true. Silence let officers have free range, with no fear of reprimand. I had to force myself to change my perspective. I had not protected myself or bettered myself by staying quiet. I had betrayed myself and others through my silence.

For two years I was a teacher’s aide in a GED class for my fellow inmates. There was one bathroom break allowed in a school day, and if you asked to use the bathroom you would not only be refused by the officer, but they would oftentimes skip over your entire class if you had asked too many times. As the only inmate allowed in the hallway during school hours, I was often asked to request a bathroom break from officers, and in the beginning, I wouldn’t do it. I believed it to be more ethical and humanist to make everyone wait the four hours until the officer let us go, instead of risk losing the bathroom break for everyone. Eventually I got so fed up with the manipulation that I went to a high-ranking officer and argued. Then I argued with the principal, who also ignored me. But the event is what made me less scared to try and fight for myself and others. I was guilty of a crime, and I also needed to pee. As did everyone else. Eventually the officer in question was removed from the post in the education building, and we were given more reasonable breaks, That wouldn’t have happened if as a group we hadn’t all broken our silence and spoken up.

I found that the only thing that would help me to speak up, and overcome my immeasurable guilt, was to remind myself of those around me, and speak out against their treatment. This strategy grew from a sense of empathy, of humanizing the other prisoners. Everyone around you has been found guilty — often of terrible crimes — but they are your neighbors, and your family while incarcerated. They deserve to be treated like humans just like we all do. But getting to this realization can be difficult for some and a test of empathy.

My dorm was tested one Mother’s Day. For over 6 hours , an inmate in the cell next to mine was denied medical care for a strangulated hernia. The officer made it very clear that he was not calling the medical unit because her crime had child victims. When I stood up to argue with the officer about his decision, I was threatened with pepper spray, handcuffed, and removed from the dorm. It was a discriminatory act that fueled my desire to break the silence behind the prison walls. I could not judge that woman for her past transgressions because I knew the person she had become; I recognized the humanity in her, which the prison itself often denied.

I found myself being shown extreme kindness and kinship from people I never expected it from. Inside the walls we learn to care less about people’s crimes and backgrounds and learn to care more about how people behave with respect and kindness on a day-to-day basis. I have been fed by women whose crimes scared me, and I have fed women who were openly upset with my transgressions as well. These are the roots of transformative justice. If I could forgive my neighbors and see their growth and goodness, then I could do the same for myself.

There are those within the walls of our prison system who see their time as a personal duty to repay their debts to our society. We don’t speak out because we see prison as something that we deserve and the cure to our crime. I grew quiet and withdrawn, I took verbal abuse from officers like it was part of my penance. I stopped telling people my name because I didn’t think I was important enough to be called by a name. Before prison I was an excellent public speaker, I loved theater and reciting my poetry to others; but now, I often spoke with a stutter just because of how scared I had become to speak aloud — to make myself heard.

Prison stripped me of everything I had and distanced me from my own identity. After my release, a close friend asked me to participate in a guided meditation where she began with us thinking of our favorite animal. It seemed such a vulnerable question that I couldn’t answer. I still wouldn’t allow myself to be human enough to have a favorite animal. The guilt prison had instilled in me lingers in many ways.

It is important that, while on the path to prison abolition, we help those who commit crimes be a part of transformative justice on behalf of their community. We must also help those currently incarcerated see that just because we feel guilt for our past transgressions, we still have the freedom to speak out against the detrimental effects of being incarcerated. Allowing ourselves to take the steps towards forgiveness and atonement of crimes would not only relieve us from the weight of personal guilt but can also help others to speak out against the failures found inside our criminal legal system.

The belief in your own freedom should channel into the freedom of others. Without that, we are sabotaging the freedom of our friends, neighbors, and community members. The freedom of everyone is possible without ignoring the guilt of ourselves and others — without destroying an opportunity for solidarity.

We are taught during incarceration that speaking out will make things worse, but if we break away from the fear, and from the anger bound to our fear, not only can we help ourselves, but we can help others. We can help to free everyone from the bounds of the system that ties them down.

***

Alayne Ballantine is a writer living in Corrales, New Mexico. She works in electronics and spends her time writing with anti-policing groups across New Mexico and Texas. She was born in Albuquerque and lived with family both in Albuquerque and in Texas. Alayne taught literacy classes inside Texas prisons, helping incarcerated women obtain their GED. She has degrees in English Literature and Philosophy, but prefers to work and write outside the world of academia.

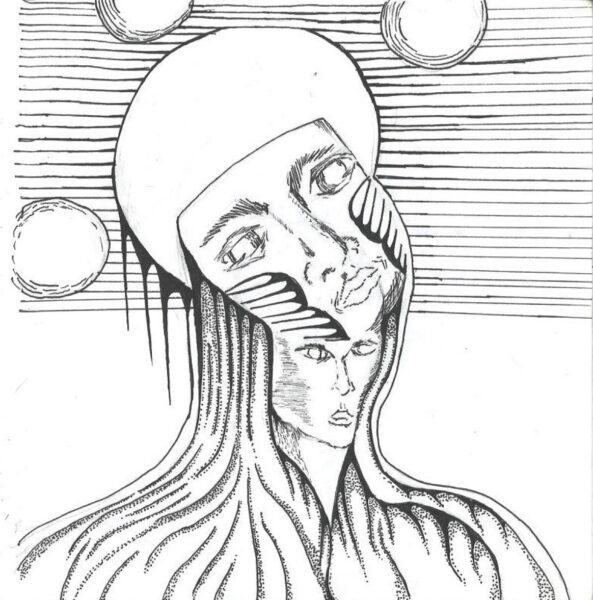

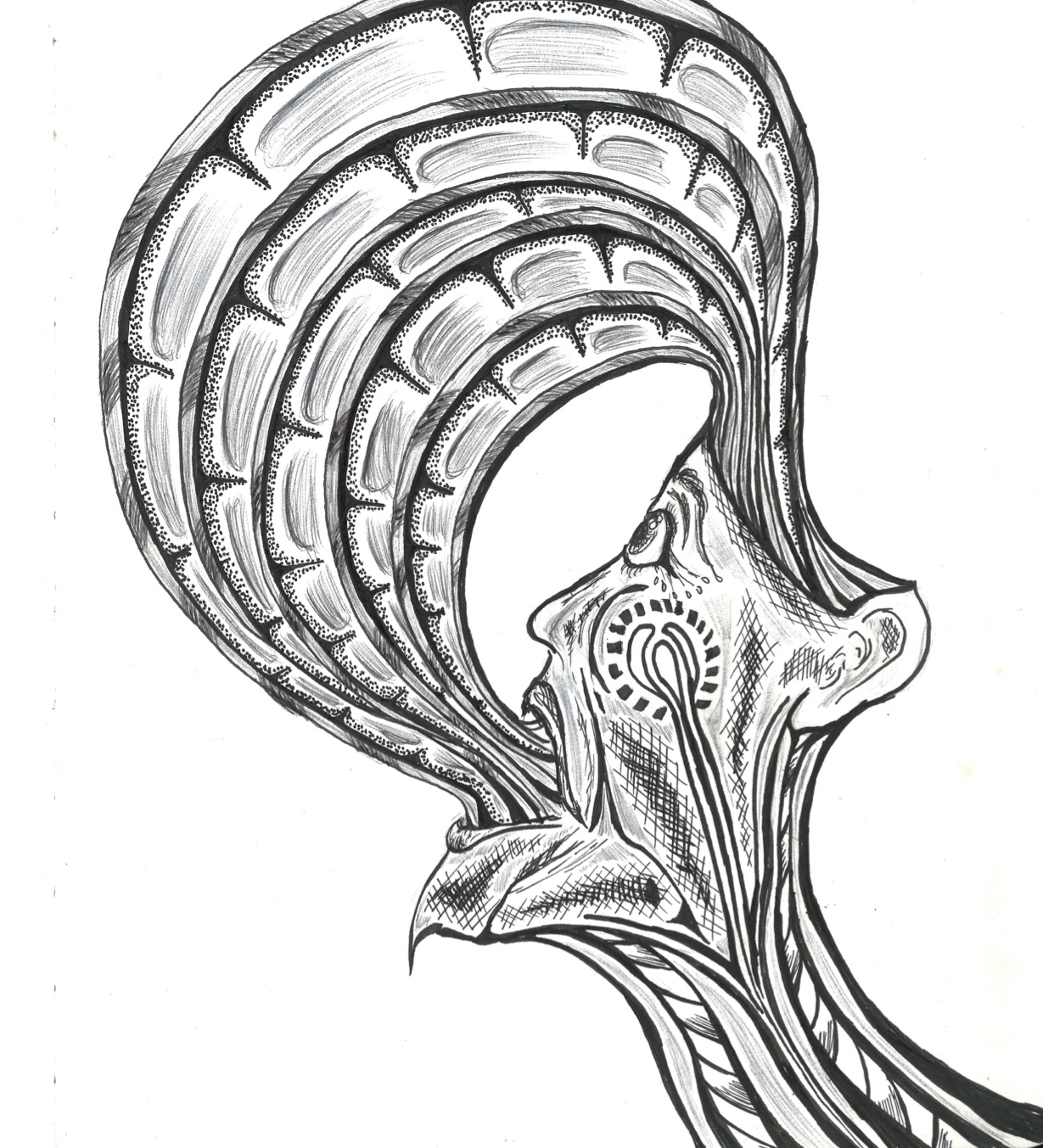

(cover art by Adri De La Cruz)

Bibliography

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, (New York: Continuum, 2007).

Ghazarian, Sydney. “Radical Solidarity in the Fight for the Future,” Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, Imaginations, N. 30, (Portland, Oregon: Institute for Anarchist Studies, 2020), 17–21.

Jacques, Lesage de La Haye, and Scott Branson. The Abolition of Prison. (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2021).

Legislative Updates, Press Release. (2022, March 9). Governor enacts historic investments to improve lives of all New Mexicans. Office of the Governor – Michelle Lujan Grisham. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from https://www.governor.state.nm.us/2022/03/09/governor-enacts-historic-investments-to-improve-lives-of-all-new-mexicans/

Lorde, Audre. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. (Londres: Silver Press, 2017).

Lydon, Jason. “Tearing Down the Walls: Queerness, Anarchism, and the Prison Industrial Complex.” Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and Desire, edited by Abbey Volcano, Deric Shannon, J. Rogue, and C.B. Daring, (Oakland: AK Press, 2013), 194–205.

Mayor Keller of Albuquerque [@mayorkeller]. (2021, Oct 19). [Infographic concerning the Metro Crime Initiative with quotes from Jennifer Barela and Maria Dominguez]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/CVOJcq-Ao0K/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

So sad this is what’s happening and I’m so sorry you had to go through all of that. Thank you for your courage to open up and speak to us about your experiences and also to speak on behalf of those who can’t! Your voice is strong and it matters! You’re opening doors for others to have a more realistic perspective on what is actually going on behind those walls. The more we learn, the better chances we have to grow and change and use our voices together for the betterment of our community by speaking up for ourselves and each other. You’re right, we are all human, and finding empathy for our neighbors is key to creating a new and better environment/experience for everyone. Bringing awareness to the darkness that occurs is one way to start the changes needed, so thank you again. We appreciate your vulnerability and strength!