I was 15, living in a suburban middle-class part of Anchorage, Alaska, when the subversive package arrived—my first committed step on the anarchist path.

It was the winter of 1996, and maybe just six months before, some anecdotes from a beloved radical teacher got me curious about a thing called anarchism. Soon enough, I was doodling circle-As in the margins of my notebooks. Then I was trying, through brute force, to make my way through Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky. Then—oh, the most cliché gateway into anarchism for kids of my demographic—I found punk rock. And there, in the insert of one of my first punk albums, I learned about AK Press. Brandishing a 56k modem, a phone, and a few hundred dollars that I got once a year from Alaska’s strange, oil-based dividend checks, I ordered a load of literature and odds and ends: Anarchy by Errico Malatesta. Living My Life by Emma Goldman, The Ecology of Freedom by Murray Bookchin, something about participatory economics by Michael Albert; Situationist pamphlets and grassroots organizing manuals; tiny punkish pins and a slew of garish t-shirts crammed with ironic faux-corporate logos, stenciled fists, and slogans in block letters. I’ll admit that, for a little while, I just basked in my new consumer identity as an anarchist. Then I actually read the stuff and, Wow, I really was an anarchist! From that cacophonous, often inscrutable, mix of texts, I found a personal worldview, ethics, even a spirituality that came to guide the course of my life.

I just turned 35. It’s been twenty years, and I’m still an anarchist. I no longer sport the fashions or iconography, but most of the key events in my adult life have been profoundly linked to my anarchism—of course all the activist projects and groups, but also the love stories, including my committed partnership of ten years; my educational journey from A-student, to unschooler, to now being a high school teacher myself; the naming and raising of my daughter; nearly all of the friendships that I’ve made and lost; and so many of my costliest, most regrettable mistakes. And beyond my own life, I’ve watched and participated as anarchist ideas and practices—if not the explicit title—have made significant contributions to global social movements. I imagine you know the list: the global justice movement, the anti-war movement, queer and trans liberation, Occupy, climate justice, Canadian anti-colonial and student movements, Black Lives Matter, and Rojava, where anarchists are on the front lines against ISIS.

But as I get older—and I imagine I’m not alone in this—and watch myself and fellow anarchists keep repeating the same self-marginalizing errors, and as I see capital-A Anarchism so easily mesh with other, more diverse, frankly less Eurocentric movement tendencies, forming what Chris Dixon (2014) calls an “anti-authoritarian current,” the question nags at me: am I really still an anarchist, or is it maybe a childhood thing—the political equivalent of a little blankie—that I’m scared of letting go of? More sharply, does anarchism in the twenty-first century offer something more than a brand for self-expression and personal righteousness, does it have something unique and important to offer to building an actual winning, transformative politics?

This is where Andrew Cornell’s Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century (2016) comes as a precious gift. It is a sweeping, enthralling history of anarchism’s march—really, more of a shuffle—across the mid-twentieth century in the United States. Throughout eight chapters and 300 pages of storytelling and analysis—all backed by another 70 pages of notes—Cornell explicitly attempts to demystify how the classical anarchism of Bakunin and Kropotkin morphed into the contemporary anarchisms we now know—from today’s class strugglers and insurrectionists, to the anarcho-primitivists, and especially to the more intersectional anti-authoritarian current I mentioned above. He traces US anarchism from what he considers its “apogee” in 1916 (21)—the eve of World War One and the peak of anarchist newspaper circulation—through a long “valley period” that was bookended on one side by the 1917-1924 Red and Black Scare, and by the sixties upsurges on the other. Cornell writes like an intrepid helicopter traffic reporter. He often flies high to survey as many anarchist tendencies and groups as possible—their stances and conflicts, their strategies and actions, their membership and readership numbers—and also to analyze how they cruised or clashed with a rapidly changing social, political, and economic landscape. But then he swoops in low, into the bedrooms, basements, prison cells, and utopian farms of select, fascinating cases—and this is where his book finds its greatest value. By the end of the book, I was stunned, dazed, teary-eyed. Chapter after chapter, Cornell thoughtfully contextualizes nearly every single piece of literature that had initiated me into anarchism back in 1996—plus almost the rest of my anarchist bookshelf!—grounding them in their own personal and political histories. It was all there, not as some flattened caricature, but as actual artifacts from generations of anarchists’ thinking, relating, struggling together—allowing me, allowing us, to more clearly evaluate US anarchism’s historical value to revolutionary work.

At first, the conclusions aren’t all that comfortable. It feels like each inspiring and heroic moment, each historically meaningful innovation—and there were plenty—was also matched by patterns of marginalization or sectarianism, of repression and defensiveness, of male domination and Eurocentricity, and of a steadily decreasing confidence in anarchism as a revolutionary mass movement, in favor of ever more subcultural scenes. By the time I reached the book’s conclusion, I felt ready—in a healthy, cathartic way—to put away my anarchist blankie. But after re-reading and processing the book for this review, I’m now in a very different place.

Of the many ways that Cornell’s book is useful, I believe that its strongest contribution is in how it helps us understand anarchism’s most unhelpful patterns, and the ways they hold back anarchism’s more expansive aspirations. With Cornell’s helicopter perspective, we can zoom out and see the antecedents and the consequences that have surrounded those less savory cycles, in a way that’s highly difficult when anarchists are in the moment, or when anarchist legacies are flattened across discrete texts. Doing this, we can see that anarchism’s liberatory potential has indeed been present, and strong, but it’s also been chained to three frustrating challenges: fragmentation and marginalization, the repetition of tactics and strategies beyond their shelf life, and, crucially, the misunderstanding and underutilization of time itself as a resource.

In the rest of this review, I want to explore how these three challenges manifest in the cyclical themes of Cornell’s book, and I will argue that by synthesizing the lessons that Unruly Equality offers, we can find renewed value and vitality in anarchism.

Repeating History: And I Thought the Star Wars and Hobbit Prequels Were Bad

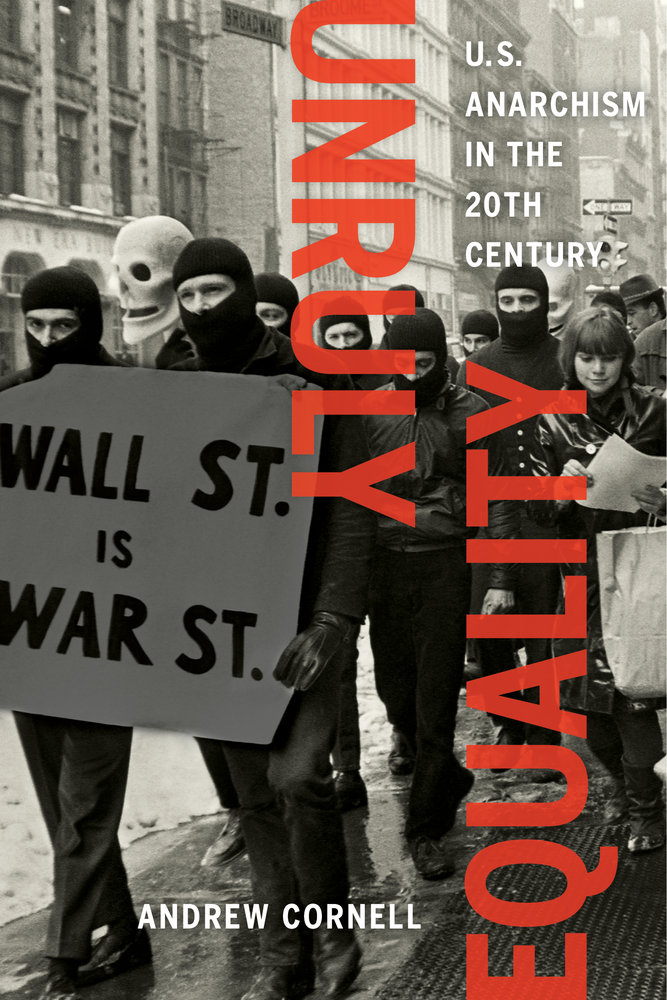

It’s right there on the cover. A handful of black masked radicals, with some kind of skeleton puppet floating behind them, holding a sign that reads “Wall St. is War St.” It could be the latest Facebook post from any recent black bloc action, but it’s actually from 1967, when the Black Mask Group (soon to be Up Against the Wall Motherfucker) took on Wall Street forty-four years before Occupy. The image excellently captures the constant sense of deja vu, of cyclical impasses that permeate Cornell’s book.

At times, Unruly Equality reads like a fanfiction prequel, packed with all the modern anarchist tropes and clichés you could imagine—just rolled back a few quarter centuries, with old timey dresses and some mustaches thrown on them. That 1967 grand-pappy black bloc was just a preview. You’ve also got the vegan raw-foodist insurrectionary, condemning technology and rejecting any need for “sane, practical movements”—in 1933 (Cornell 2016, 115). You have the anarchist couple inspired to move to the Bay Area, form a collective house, experiment with open relationships, and then move away brokenhearted—in 1946 (193-194). You have the effective and influential anarchist veteran who strays too far from anarchist orthodoxy, and then is called out so bitterly that he permanently distances himself from anarchism—in 1965 (235-236). And across far too many of these decades you have those too-familiar anarchist stories, of women being oppressed and undervalued in the movement, and of the revolutionary agency and experiences of communities of color being misunderstood or altogether unseen—that is, until their movements were already too huge to ignore.

At times, I physically winced as I read stories that cut too close to home, or that provoked anger about anarchism’s more brutal cycles—especially the repeated terrorist bombings, despite decades of experience that showed their ineffectiveness. But to stop there, to stay there—with the snark and head-shaking of hindsight—would be a great disservice to ourselves, to Cornell’s indispensable investigative work, and to the real lessons of life and struggle that these real anarchist human beings have to teach us. It’s not enough to be frustrated by anarchism’s various unproductive, even destructive cycles; we have to try to understand why they are cycles in the first place.

The first piece of the puzzle comes from the gargantuan implications of the anarchist ideal itself. Even in its classical period, when its vision of liberation was limited merely to the abolition of capitalism, the state, and the hierarchical church, anarchism has always carried a heavy load: complete emancipation and equality for all. As if that weren’t already tough enough to conceptualize within the bounds of concrete action in the world, Unruly Equality unfolds the story of how mid-twentieth century anarchists deeply expanded those classical understandings of liberation across realms of psychology and sexuality, ecology and individual self-realization, and eventually—and with considerable help from feminist and anti-racist struggles—to intersectional opposition to all forms of hierarchy and domination. By its very nature as an unflinchingly utopian and deeply universalist body of ideas, anarchism in practice is made up of millions of moving parts—not just between individual people within social struggle, but also within our own lives and psyches, and within our relationships to the natural world.

Given this, it shouldn’t surprise us that anarchists are still repeating so much of our own histories in frustrating and infuriating ways. And it should surprise us even less when we stack our history up against the other three challenges that repeatedly show up in Cornell’s book.

Fragmentation: Our Siloes Will Not Protect Us

For me, Unruly Equality confirmed that anarchism does have a beautiful, unbroken legacy of earnestness, of raucous creativity, of a searching and expansive interest in the freedom and equality of all. However, these strengths have always been limited by the actual, fragmented social realities of anarchists as people. While we modern anarchists chafe against the real complications of identity politics, and the digital insularity that social media and subcultural bubbles create, Cornell powerfully demonstrates how US anarchism began as a deeply fractionalized movement in its own way. Anarchists, the vast majority of whom were from Southern and Eastern Europe, were racially vilified as immigrants, and fragmented not just across ideologies, but also languages, ethnicities, cities, industries, and socialized gender roles. Siloed in these ways, anarchists have long centered our own surroundings at the expense of the universalist solidarity we espouse.

Examples of this are legion throughout the book, but I think the most consequential came in the 1920s, and then again in the 30s and 40s, when the still predominantly Southern and Eastern European anarchists—already sensitive to their own racialization and marginalization from an English-speaking majority—failed to deeply embrace the great migrations of African-Americans to their very same neighborhoods and workplaces (Cornell 2016, chap. 2). This directly contributed to classical anarchism’s decline starting in 1917. Disappointingly, anarchists only sided en masse with Black struggles when those struggles were already popping off decades later in the deep South—and when anarchism’s working class mass base had already been mostly replaced by middle class, college educated activists. A less damning but still consequential example comes from Cornell’s stories of how 1940s and 50s anarchists—especially the avant garde surrounding Kenneth Rexroth and Paul Goodman—responded to post-WW2 labor peace and rising consumerism with a sharp turn inward, shifting the emphasis of revolution from a mass reconfiguration of economic and political power toward a much more personal awakening (chap. 6). While this helped usher in vital developments such as queer liberation, the Beat movement, and major elements of sixties counterculture, it also inaugurated the lifestyle-centered subcultural scenes that still cast long shadows on today’s anarchism.

Cornell’s book gave me numerous moments of pause. I was moved to reflect on how, right here in Seattle, my own personality, my social positioning, my ideological self-selection all end up limiting the potential of my own anarchism. It also inspired me with how certain individuals—and not all of them anarchists—including Emma Goldman, Holley Cantine, David Dellinger, David Wieck, Diva Agostinellii, Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker, and young Murray Bookchin were able to individually counteract those siloing tendencies, so that anarchistic ideas could help build powerful social movements.

Expired Tactics: It Worked Once, So…Well, Let’s Just Run it Into the Ground

While anarchists have often been top-notch at tactical creativity—from the Francisco Ferrer School’s experimental education, to the Italian Galleanisti’s mastery of clandestine security culture, to the myriad innovations in both art and non-violent direct action that cascaded across and beyond the sixties and seventies—our siloed realities have seen us constantly applying old tactics that are inappropriate to new contexts. The highly-effective solidarity and defense campaigns of the 1910s devolved into a demoralizing rut of constant defensiveness when the communists and fascists ascended in the 1930s (Cornell 2016, chap. 3). The groundbreaking art and sexual liberation of the 1940s Californian anarchists gave us what became in part the apolitical, drug-addled countercultural scenes of the late sixties and seventies (chap. 6, 8). Anarchists’ block-to-block street-fighting prowess and our militant nonviolence have both ossified into symbolic gestures of resistance that often have little political impact.

From the book’s cover to its epilogue, which briefly follows contemporary anarchism all the way to the present day, Unruly Equality reminded me of how uniquely brilliant and useful anarchism can be when it’s not simply repeating its politics, but reinventing them in the grounded realities of actual movements.

Time: A Most Undervalued Resource

Across US anarchist history, the twin factors of fragmentation and strategic stagnation have both been exacerbated by the ways that anarchist time has been fractured, misunderstood, and underutilized. By allowing us to see the anarchist story play out across time, Unruly Equality helps us with some big takeaways.

First, a key reason that anarchists keep repeating history is because we haven’t been allowed enough stable time to grow through organic, intergenerational praxis. Cornell explores how repression, linguistic barriers, changes to immigration policy, anarchist child-rearing approaches, and anarchists’ own sectarianism all served to disrupt the anarchist timeline. Indeed, one of the most thrilling portions of Cornell’s book is its explanation of just how narrowly anarchism survived at all at the end of the 1930s—passed almost hand-to-hand, like friendship bread, between maybe a hundred young radicals. Some had been mentored by anarcho-syndicalist elders. More were inspired by the staggering work of the anarchism-infused Catholic Worker movement. Others discovered anarchism from just two tiny publications—the most impressive of which, Retort, was hand-printed by a Thoreau-influenced couple living in the woods. And, fascinatingly, the most significant transmission and evolution of anarchism in this valley period came from within World War Two prisons, when anarchists, pacifists, and conscientious objectors organized to desegregate their prisons and galvanized a new generation of non-violent anarchist revolutionaries—now woefully understudied and misrepresented by current anti-pacifist attitudes. But these stories show how lucky we are that anarchism was able to survive and evolve at all, because of how thoroughly broken the anarchist timeline became (Cornell 2016, chap. 4-5).

Second, anarchists have struggled with our own conceptualizations of the scale of revolutionary time, and this has had devastating consequences for how we manifest urgency and patience with each other, and in our political strategies. Cornell tracks this changing sense of time, as classical anarchists perceived mass uprisings and revolutionary reconstruction to be mere years away—perceptions that were temporarily confirmed by the Russian and Spanish revolutions—but later generations slid toward ever more gradualist, even personalist, conceptions of revolution, or discarded the idea of revolution altogether. This swinging between believing revolution is around the corner or that it blossoms slowly, even Zen-like, from within the individual, affects how anarchists plan, how we frame our ideas, how we handle intra-movement conflict, and how we work with non-anarchist populations. Now, with the abundant lessons of history, I think modern anarchists are poised to embrace a more nuanced and confident understanding of revolutionary time. We can recognize that yes, transformative political ruptures—your Greeces, your Arab Springs, your Quebecs—can open at any moment, and we should be prepared. But we need to see that these are just moments of uprising on a much longer road of antiauthoritarian emancipation—with room for patience, experimentation, and mutual care, especially when we inevitably need to recover from repression.

Taken as a whole, Cornell’s book made me consider how a long-haul view of revolutionary time, combined with a shared dedication to maintaining and nurturing intergenerational anarchist praxis, can make anarchism’s evolution far more dynamic in the twenty-first century than it was in the rocky twentieth. Interestingly, for me this is modeled most movingly in the book by a group of aging Italian insurrectionists that kept popping up each decade to support younger organizers (Cornell 2016, 196, 205, 267). As an older and more settled anarchist, as a teacher and a father, this is where I’m most excited. The twentieth century showed us the expansive, universalist, downright poetic and spiritual ideals that make anarchism attractive, yet really only hinted at its tactical and strategic possibilities; through decades more of intergenerational continuity, I think the twenty-first century is where anarchist practice could blossom into a winning politics.

Conclusion: Not Just a Childhood Toy, But a Companion in Growth and Struggle

At the end of my second reading of Andrew Cornell’s Unruly Equality, I leaned back in bed, my daughter sleeping on my chest, and took stock of my thoughts. Of course, anarchism is not the be-all, end-all of antiauthoritarian movement building. There is plenty of room in our ecosystem of movements for many tendencies and identifications. But nonetheless, “the beautiful ideal” (Cornell 2016, 25) that lies at the heart of anarchism—which served as a shared motivation for so many previous generations of radicals portrayed in Cornell’s book—is an ideal that remains embedded in my own heart—not just as a feel-good self-identification, but as a foundation for political practice. Even more, when I combine the historical insights of Cornell’s book with the more contemporary insights of Chris Dixon’s Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements (2014)—and I do recommend reading the two books close together—I am overwhelmed by the possibilities that exist for a radical future. I look forward to what part anarchism will play in that future, and how my life, our lives, will be changed over the next twenty years, forty years, and beyond.

Jeremy Louzao is a long-time anarchist organizer in the Seattle area, whose experiences have included global justice affinity groups, collective community info-shops, anti-violence support groups, youth empowerment non-profits, Guatemalan campesino communities, and recently high school teaching and school transformation work.

References

Cornell, Andrew. 2016. Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century. Oakland: University of California Press.

Dixon, Chris. 2014. Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements. Oakland: University of California Press.

Fink, Larry. [Demonstration by the Black Mask Group]. New York: 1967. Photograph. In Cornell, Andrew. 2016. Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century. Oakland: University of California Press, front cover.

Andy Cornell will talk about his book, Unruly Equality, on Saturday, May 28th, 2016 from 6 – 8pm at Mother Foucault’s Bookshop (523 SE Morrison St) in Portland, Oregon.

1 thought on “Coming of Age: A Review of Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century, by Andrew Cornell (University of California Press, 2016), by Jeremy Louzao”

Comments are closed.

Reblogged this on The Free.