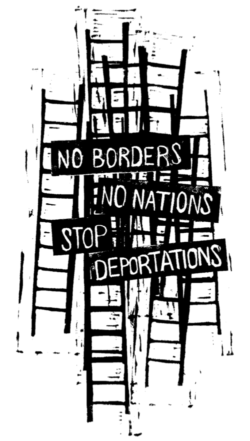

| (art by Amanda Priebe) |

“The world we want is one where everyone fits. The world we want is one where many worlds fit.”

Fourth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos,

Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), January 1st, 1996

Destitute Times and Rebellious Imaginations

On the first day of 1996, the Zapatistas—the indigenous rebels of Chiapas, who had exactly two years earlier taken up arms against the imposition of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the creep of neoliberalism, and the privatization of communal life— proclaimed that “the flower of the world will not die.” (1) Their declaration takes its name from the Lacandón Jungle, the massive rainforest that stretches across southern Mexico and Guatemala and, like most organic entities, refuses to recognize state formations and national boundaries.

In this statement, Subcomandante Marcos wrote: “el mundo que queremos es uno donde quepan muchos mundos”: the world we want is one where many worlds fit. Even in the space of militant resistance, the Zapatistas demand diversity—emancipation arrives through an embrace of multiplicity. No claim is being made to a future without difference for it is heterogeneity which cultivates inventiveness. Instead, an aspiration is asserted for a world in which difference is not laden with power and inequity, a future in which the powerful cease to deny “space for anyone but themselves and their servants.” There needs to be space for everyone’s experience.

The Zapatistas move beyond traditional Western liberal ideas of justice to what might be called an insurgent universalism, which affirms the agency of subjugated people who fight from specific conditions, but who do so for the freedom of everyone. (2) This kind of intersectional universalism can be seen as an emancipatory and abolitionist project. (3)

Multiple meanings emerge in the Zapatistas’ insurgent statement. Querer, the root of queremos, connotes desire, affection, and aspiration as much as it does want. The desire bound up in querer leads us on a search for something that is not-yet. We revel in this search, in imagination-in-motion. Que queremos—what we want—is not just a demand, but also a daring act of imagination. (4) This double reading of “want” as “imagine” moves us to think about the future in a more open way: the plural futures we imagine offer many escapes from the austerity and alienation of the present. Destitute times call for a diversity of tactics; rebellious imaginaries offer a wealth of departures.

“Possibility is not one,” Franco Berardi writes, “it is always plural.” (5) A multitude of futures exist, always already inscribed in the present as an “immanence of possibilities” fluctuating between realms of realization. Every moment is, at the same time, a loss of nonactualized potential. Loss can be mournful, but it can also be generative.

If alternate futures emanate as a sort of ever-present specter, who is responsible for its actualization? Berardi answers clearly: “Us.” (6) He reminds us of the “humiliated people” everywhere who are dispossessed by capitalists, yet because of their dispossession they exhibit the potential for dignity, autonomy, and the horizon of communism—of a world where “richness is for everybody.”

Autonomous forms of organizing seize potentialities, articulating imagination into material reality. Praxis is embodied in revolt, receiving fullness in moments of self-governance. Recognition of the future as already-here mobilizes a prefigurative mode of politics. That is to say, the future we desire is within reach.

As an abstraction, freedom feels unfamiliar. It possesses a bigness, an out-thereness that feels out of reach from the here, the present. But when people come together to decide for themselves how to live life and care for one another—whether it means throwing down in the streets against the police, building barricades and occupations in public squares, defending against evictions and doing court support, or organizing community spaces and feeding each other—new powerful bonds based in struggle emerge.

In other words, “friendship is the root of freedom.” (7) It is what makes freedom flow into tangible existence. As Byung-Chul Han writes:

Originally, being free meant being among friends. ‘Freedom’ and ‘friendship’ have the same root in Indo-European languages. Fundamentally, freedom signifies a relationship. A real feeling of freedom occurs only in a fruitful relationship–when being with others brings happiness. But today’s neoliberal regime leads to utter isolation; as such, it does not really free us at all. (8)

In contrast to capitalist discourses of independence, recognizing one’s inseparability from others is not a sign of weakness. Rather, plenitude and emancipation are possible only when we positively affirm our ties to community. Radical imagination seizes richness, what Kristin Ross calls “communal luxury.” (9) What use do we have for wealth if it does not belong to everyone?

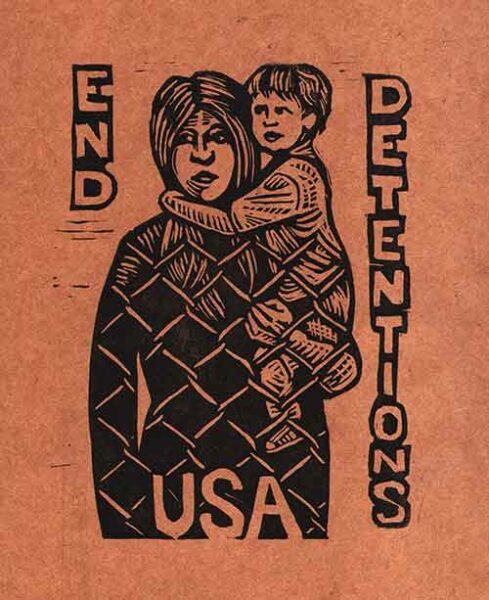

Abolitionist calls for the end of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) exploded in the summer of 2018, blossoming joyfully across the country. Thousands of ordinary people witness to the violence of the state were driven to action, pouring into the streets. Much like the morning glories which bloom in the summer months, so too did a wave of occupations and street protests. In at least ten cities in the US, encampments were established outside of ICE offices and held for days to weeks.

What began in many places as symbolic, if disruptive, protests against the cruelty of border imperialism (10) and the criminalization of migration, rapidly transformed into an open affront against all forms of colonialist and nationalist violence, and against capitalism and the nation-state as a whole. Protesters creatively engaged with worlds not-yet-ours, with worlds in-the- making.

The occupation as a type of “autonomous zone” offers a rich site of investigation. They are established with fullawareness that the occupation will not last forever. Its calls are never simply situated within siloed-off struggles but instead lay claim to the whole horizon. The Invisible Committee, an anonymous collective of insurrectionary anarchists, attests to this emancipatory spirit:

Contemporary communes don’t claim any access to, or aspire to the management of any ‘commons.’ They immediately organize a shared form of life—that is, they develop a common relationship with what cannot be appropriate, beginning with the world. … Every moment, however, every genuine encounter, every episode of revolt, every strike, every occupation, is a breach opened up in the self-evidence of that life [a life of atomized existence], attesting that a shared life is possible, desirable, potentially rich and joyful. (11)

In a world that seems desperate to isolate us from one another, the work of imagination is central to envisioning and constructing alternative forms of life, and in cultivating a space for inventive discovery.

When the Abolish ICE San Francisco camp came together in early July 2018, two young organizers of color, Imri Rivas and Zoé Samudzi, spoke alongside Cat Brooks in a press conference. Rivas invoked a crucial question when responding to reporters: “What would society, if borderless, look like? … What if we create areas of mutual aid, where people can come together and build communities?” (12)

Their questions signified a form of willful speculation which looks to the prospect of worlds to be imagined and created. This prospect is also a process. Autonomy is not a fixed idea but a mode of becoming which is always in motion. It materializes through affinity, care, and intimacy.

Turning to the idea of constellations, Jackie Wang articulates “the need for both social imagination [and] material acts.” (13) When people converge to support one another and create new forms of life together, affinity “becomes not just a matter of shared personal political beliefs, but the entwinement of our everyday lives.” Constellations give meaning to our web of relations. In this way, Wang resonates with Nick Montgomery and carla bergman, who write:

When people find themselves genuinely supported and cared for, they are able to extend this to others in ways that seemed impossible or terrifying before. When people find their bellies filled and their minds sharpened among communal kitchens and libraries, hatred for capitalist ways of life grows amid belonging and connection. When someone receives comfort and support from friends, they find themselves willing to confront the abuse they have been facing. When people develop or recover a connection to the places where they live, they may find themselves standing in front of bulldozers to protect that place. When people begin to meet their everyday needs through neighborhood assemblies and mutual aid, all of a sudden they are willing to fight the police, and the fight deepens bonds of trust and solidarity. Joy can be contagious and dangerous. (14)

The formation of new worlds and ways of life is a creative, experimental, and joyful process. No blueprint will chart our emancipation. Joyfulness does not preclude grief, mourning, or anger; rather, it is constituted by a capacity to hold these feelings together with collective catharsis and community-building. As my friend Felix once told me: complexity does not entail negation. Rather, it is an embrace of vibrancy, flux, and difference.

Thus, the creation of the commune and occupation invokes our imagination in a way that finds likeness with what Donna Haraway calls “speculative fabulation,” an open and fluid form of storytelling that centers imaginative fable-making and joyful world-making. It is precisely the kind of thinking that Imri Rivas deployed. Thinking with storytelling pushes us to ask: what stories will we write, and what worlds can we enact? what characters inhabit our narratives? can the streets be the site of our next fables?

No One is Illegal on Stolen Land: A Brief Interlude on Solidarity Against Border Imperialism

“in spring we’re reborn / just as the buds do blossom / write history not by / ink and pen but by the / stones we hurl at / those who wish to bind us / break up the pavement / find what lies beneath it” ——La Bella, 2016

From Palestine’s annual Great March of Return to the Central American migrant caravans to the Abolish ICE occupations, people around the world are rising up against systems of colonial borders.

Since late in 2018, a self-organized collective of several thousand Central American migrants have been traveling north towards the Mexico-US border. (15) Though these are certainly not the first such caravans, they have been the most visible in recent memory. To borrow from the poet Antonio Machado, the caravan quite literally makes the way by walking; they embody the “purposeful will of the people” to imagine themselves as actors and authors of their own stories, as Peter Hallward writes. (16)

The mass exodus of migrants reminds us that strength is to be found in numbers and solidarity in mobilization. It is an experiment of self-governance in motion. The migrants speak for themselves. They articulate their demands not just through collective exodus, but also through makeshift general assemblies, organized crews for self-defense, and the creation of temporary communities along the way. An observer recounts a nightly assembly organized by members of the caravan:

For 90 minutes, the members of the caravan paid close attention to the decisions facing them in the coming days and to the words of local and national organizations that had come to support them. Members of the caravan took the stage to explain why they nominated themselves to represent the group in negotiations with Mexican authorities. Trans women in the caravan took the mic to demand respect from the rest of the group. … The assembly created a space for the interests of working class, indigenous and migrant organizations to come together. (17)

In Juchitan, Oaxaca, a local supporter of the caravan proclaimed to migrants, “You have been capable of facing down the world’s borders … proving that no one is illegal.”

In late November 2018. the caravan reached the San Ysidro checkpoint in Tijuana, where they were met by police decked in military gear who lobbed tear gas across fences. It is important for those of us on this side of the colonial border to remember our responsibility to also reject its authority. Waves of support are slowly making their way south with people offering aid, but the future remains to be seen.

Activists have worked for years to draw out the transnational relationships forged under US imperialism. Tear gas offers a nexus for such an exploration. When chemical weapons like tear gas, manufactured in the US, are used in both Palestine and on the streets of the US, solidarity is suddenly made visceral and embodied—we are literally connected by the air we breathe, and the gas. (18) For people rising up against police violence in many places you can hear the chant, “From Ferguson to Gaza, long live the intifada.” In the midst of the Ferguson, Missouri uprisings following the police murder of Michael Brown in August 2014, many Palestinians proclaimed, “The empire will fall from within.” (19)

Palestinians at the time were experiencing a massive military siege themselves. The shared experiences of state violence ties protesters on the streets of the US to the migrants at the border also experiencing state violence and to those in Gaza and the West Bank. This is attested to in a recent and heartwarming message of solidarity from the caravan which read, “In solidarity with Gaza—together we will tear down these walls.” (20) The dispossessed recognize each other.

The Occupation is Gone but It Lives Forever: Abolish ICE San Francisco and its Aftermath

“All we ever wanted was everything” ——Bauhaus, 1982

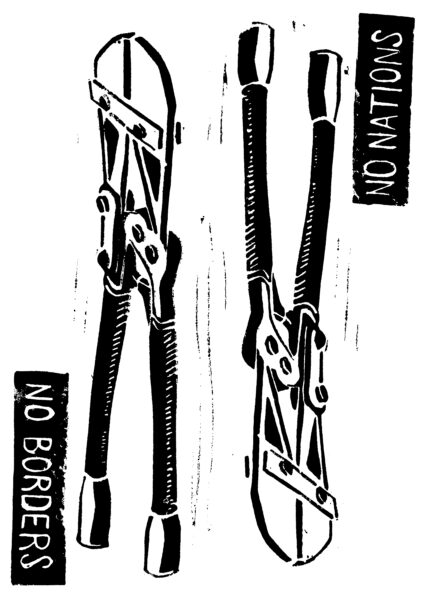

Borders foreclose the horizon of possibility. Territorial boundaries seek to dismember the organic flows, continuities, and assemblages which constitute our world(s). Pieces of the earth are held in suffocating isolation from each other; such divisions are reproduced and inscribed onto our bodies, manufacturing us as subjects.

But Empire is not built on terra firma: it is not inevitable, nor is it eternal. It is bound to collapse, and it is our responsibility to accelerate its demise. So, when the Abolish ICE occupation converged in San Francisco, our demands were quite simple. When news reporters would ask us, “What will it take for you to leave?” we would respond resolutely: only the immediate and total destruction of the border.

Plenitude is found in community, through learning from and living fruitfully with others. The nights I spent at the San Francisco occupation, among friends and strangers who quickly became friends, were the most liberated that I have ever felt. Recalling Han’s elaboration on friendship and Marx, “being free means nothing more than self-realization with others.” (21)

The occupation sprang from a protest that took place in the wake of several other actions around the Bay. First against the construction of an immigration detention center in Concord, California, then against an existing facility in Richmond, and so on, all driven by an urgency to do something. But this protest felt different. It was born of different aspirations.

On July 2, folks from around the Bay converged at the San Francisco ICE office to celebrate resistance. The banal processional march was replaced with displays of convivial joy alongside collective rage, grief, and commemoration. Music, slam poetry, and open mic sessions filled the air, leading to an anonymous crew constructing a barbed wire fence to block the doorway, all culminating in the formation of a massive human wall of demonstrators. Arm-in-arm, several hundred protesters linked together to form a barrier around the building—a literal embodiment of mass solidarity—effectively sealing it right as employees would be eager to leave work.

Though this mobilization was by and large a peaceful, symbolic one, we were reminded in a training session days before the action of the still-present danger of repression. Power tripping police, irate employees, and alt-right agitators all posed a threat. We—and at that point, “we” was still a set of mostly-strangers who met at the training—practiced screaming in each other’s faces and pulling apart locked arms to learn to sit with discomfort and tension.

But what drives people to knowingly embrace such vulnerability? To put one’s body on the line? Meditating on this, Judith Butler writes,

[A]ll public assembly is haunted by the police and the prison. And every public square is defined in part by the population that could not possibly arrive there; either they are detained at the border, or they have no freedom of movement and assembly, or they are detained or imprisoned. … Sometimes we walk, or run, knowingly in the direction of prison because it is the only way to expose illegitimate constraints on public assembly and political expression. (22)

That is to say, vulnerability is generative. It can become the very medium through which we enact our politics. The living blockade exposes the injunctions imposed on us by imperialism and xenophobia.

As the demonstration wound down in the evening, tents were conspicuously deployed and the call for an occupation went out. San Francisco had thrown in its lot with the seven other cities who had, at that point, joined the wave of occupations.

By laying claim to the city space, a narrow but crucial corridor on Washington Street nestled between Battery and Sansome, protestors struck at the heart of the anti-immigration apparatus in the Bay Area. The encampment not only made visible the exclusionary violence of borders—in other words, acknowledged those who could not be present—but also disrupted the logistical space of flow, liberating public space for public good. The age of logistics, ushered in by an ever-expanding cybernetic network of surveillance, prioritizes the logic of orderly flow above all. In opposition to the so-called disorderly masses of migrants and protesters alike, the operation of agencies like ICE depend on regulated circulation.

But we flourish in this realm of chaos. Disruption, the embrace of ungovernability, is a “profoundly political tactic.” (23) The commune, protest, and riot all take to the street to subvert this perspective logic of order, developing a radically different conception of infrastructural space.

A vision and demand for fruitful life emerged. A zone of mutual aid blossomed. Folks quickly and collectively organized a kitchen, a tent for medical supplies, and sleeping spaces for people to join on a whim; over the next few days, a table for DJ equipment was set up, a space for general assemblies, barricades, even an outdoor toilet. Across political tendencies and social difference, a counter-logistics network flourished to sustain the camp.

Though the encampment was localized to a city block, it laid claim to the whole horizon, a whole new world, stitching together a novel geography of liberation. A sense of solidarity stretched out far beyond just San Francisco and even the network of occupations, leaping border fences and prison walls alike. “Our struggles are not separate,” the National Prison Strike committee reminded us; border abolition is prison abolition. (24) On July 5, when we got word that anonymous comrades from Chile published a statement titled “Solidarity to the #ICEbreakers,” a handful of us gathered to read it aloud, taking turns speaking into the microphone:

… The only way to ensure our survival is to secure the conditions to meet our needs autonomously.

That may mean crossing a border without a government’s permission.

This is not a neoliberal call for transnational flows against the power of the state.

Currently capitalism is only sustained by the political barriers that divide us.

This is a war cry from our precaritized bodies.

The only actions that can insure our survival are those that break the division

between citizen and noncitizen, the barrier of paternalism and exclusion…

This could mean barricading the entrance to an ICE facility, blocking a deportation bus, or hiding undocumented immigrants from the police instead of pretending that the state will protect them…

Above all, this means building the infrastructure for our shared survival…

On either side of a border, whoever they vote for, we are all illegal. (25).

Some of us snapped, others clapped, all cheerful for our new friends in Chile. Together we felt powerful. The occupation enabled us to inventively reach across space. From its formation, Abolish ICE contained already something more than just a set of demands. It offered a way of relating to one another in opposition to alienation. It embodied the prospect of an insurgent universality: we fight here because we do not fight alone.

The building that houses the ICE offices towers hauntingly overhead, its austere and monolithic exterior dominating the space around. Its nonhuman scale intends to make people feel infinitely small, as though bowing down to the power of state bureaucracy. Yet the occupation rejected this imperative. We made ourselves larger than life itself, our presence a burden, a blister, a thorn—ugly, unavoidable, and so beautiful.

An unregulated rhythm of life pervaded through the camp: a sort of queer temporality liberated from the capitalist mandate for permanent productivity. It was unlike anything I had ever felt before. The circumstances that drove us to occupy this space were quite urgent, yes, but our presence there felt truly free. Some folks participated in workshops, others chose to work in the kitchen or in self-organized security teams, some simply read alone. Others built gardens, while still others built barricades. Pleasure and duty were made one; the occupation was itself an “occasion for celebration.” (26) We watched the sun rise with glee as office workers hurried to work. When the sun set, we partied into the night. I danced until 2 a.m. during my first night at the camp. I learned the meaning of bliss.

The resonant beats of four-to-the-floor music echoed through otherwise empty streets, filling it—and us—with euphoric energy, expanding the already porous boundaries of the encampment outward. The movement of dancing bodies in conjunction to music rejected capitalist time for something different, for unrestricted mobility. The dance floor became a space of possibility, cultivating “collective intimacy that breaks with the atomized existence of passive consumption.” (27) We explored novels ways of relating to ourselves, others and the space around us.

But how does one choose to dance when your space is being constantly surveilled and intruded upon by police? When your body aches from a day of marching and building and laughing? When it is cold out and you’re hungry and you have to sleep in a tent? You do it because you’re filled with an emancipatory joy, because the people you’ve just met have become your friends and you are quickly falling in love with everyone around you.

Love and affinity, like vulnerability, thus becomes a productive political force. It enriches life and livelihood. We are reminded of the mythologized memory of the Columbia University students who fifty years ago married each other while occupying their school, and more recently, of two queer migrants from the caravan who married each other in Tijuana.

Grief pushes us to the streets too. After police raided the camp on July 9, ruthlessly arresting thirty-nine occupiers, people turned to vigil instead. They showed up every week to light candles and pray outside the ICE building. Likewise, days after a white supremacist murdered eleven worshippers at a Pittsburgh synagogue in late October, a collective of Jewish leftists held a powerful display of resistance and mourning on the street where the occupation once was. Drawing connections between anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant racism, they urged us to reaffirm our commitment to “safety and solidarity,” and to stand with the most marginalized. (28)

Trauma, grief, and pain remind us that we are resilient. This is a call for resilience rooted in community.

Not long ago, I sat with a friend whom I had not seen since last July. They had been at the camp the night of the raid. The arrest left them with lingering trauma, but despite this, they also proudly stated that the occupation had given them a new sense of confidence. It had taught them that they were in fact capable of a lot. Militancy can be transformative. The creation of “other forms of life” teaches us to be “more capable, more alive, and more connected to each other.” (29)

To recall a phrase from May ‘68 France: sous les pavés, la plage: Beneath the pavement, the beach. And the garden. And the occupation. There is an abundance of potentially rich, fulfilling, and thriving possibilities to explore when we strip away the varnish and decay of capitalism. The communist way of life (or rather, lives) not only socializes labor power, but it also offers a different relationship to power. Richness is for everybody. We are powerful together. Thus, the demand for border abolition is also a demand for worlds not held in isolation, for communal luxury, and for futures worth fighting for. Futures we can begin to grow now.

Erfan Moradi is a radical academic and student of History and Geography at UC Berkeley. They are a queer Middle Eastern immigrant living on Chochenyo Ohlone land in California. They spend much of their time dreaming about little-c communism, collective power, and radical imaginaries.

This essay is from the Imaginations issue of Perspectives (n.31). The whole issue is available from Powell’s Books here! and AK Press here!

Notes

- Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, “Fourth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle,” January 1,1996.

- Asad Haider, Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump (London: Verso, 2018), 108.

- Laboria Cuboniks, Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation (London: Verso, 2018), 50.

- I am deeply thankful to my friends and comrades Jess Alvarenga and Felix Linck-Frenz for these wonderful interventions, translations, and insights.

- Franco Berardi, Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility (London: Verso, 2017), 1.

- Franco Berardi, “Trump, Humiliation, Populism: Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi in conversation with Verso,” Verso, 18 July 2017, video, 13:12, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZ4BHIIhQ0Y.

- Nick Montgomery and carla bergman, Joyful Militancy (Chico: AK Press, 2017), 83.

- Byung-Chul Han, Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, trans. Erik Butler (London: Verso: 2017), 2.

- Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune (London: Verso, 2016), 50. Emphasis added.

- This term comes principally from the work of Harsha Walia in her book Undoing Border Imperialism (Chico: AK Press, 2013). It is constituted by (1) mass displacement and securitization of borders, (2) criminalization of migration, (3) racialized hierarchies of citizenship, and (4) exploitation of migrant labor.

- The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, trans. Robert Hurley (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2015), 208.

- Anti Police-Terror Project (@APTPaction), Twitter, July 3, 2018, 4:10p.m., https://twitter.com/APTPaction/status/1014285263546171392.

- Jackie Wang, “Oceanic Feeling & Communist Affect,” Friendship as a Form of Life, 2016, http://friendship-as-a-form-of-life.tumblr.com/post/162453258727/friendship-as-a-form-of-life-friendship-as-a.

- Montgomery and bergman, Joyful Militancy, 31. Emphasis added.

- PBS notes that “[n]o group has taken responsibility for organizing the current caravan,” though past caravans have sometimes been organized or facilitated by humanitarian groups. See Larisa Epatko and Joshua Barajas, “What we know about the latest migrant caravan traveling through Mexico,” PBS Newshour, October 22, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/what-we-know-about-the-latest-migrant-caravan-traveling-through-mexico.

- Peter Hallward, “The will of the people: Notes towards a dialectical voluntarism,” Radical Philosophy 155 (May/June 2009), 17.

- Martha Pskowski, “The Rebel Project of the Caravan: Solidarities and Setbacks,” Viewpoint Magazine, November 30, 2018, https://www.viewpointmag.com/2018/11/30/the-rebel-project-of-the-caravan-solidarities-and-setbacks.

- Mark Molloy, “Palestinians tweet tear gas advice to protesters in Ferguson,” Telegraph, August 15, 2014, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/11036190/Palestinians-tweet-tear-gas-advice-to-protesters-in-Ferguson.html.

- “PFLP salutes the Black struggle in the US: The empire will fall from within,” Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, August 19, 2014, http://pflp.ps/english/2014/08/19/pflp-salutes-the-black-struggle-in-the-us-the-empire-will-fall-from-within/.

- Jewish Voice for Peace, “‘You always have to remain standing’ Message to Gaza,” Facebook, December 3, 2018, 6:14p.m., https://www.facebook.com/JewishVoiceforPeace/videos/328675947947641.

- Han, Psychopolitics, 3.

- Judith Butler, “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance,” in Vulnerability in Resistance, ed. Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 20.

- Deborah Cowen, The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 231.

- Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, “Prison Strikers Issue Statement: ‘ABOLISH ICE!’,” Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, June 19, 2018, https://incarceratedworkers.org/news/prison-strikers-issue-statement-abolish-ice.

- “Solidarity to the #ICEbreakers: From Those Denied Entry into the US (& Their Friends),” CrimethInc., July 5, 2018, crimethinc.com/2018/07/05/santiago-de-chile-solidarity-to-the-icebreakers-from-those-denied-entry-into-the-us-their-friends.

- Ross, Communal Luxury, 96.

- No Lite Collective, “Rebels Wanna Rebel,” interview by Matt Casciano and Charles Hellier, Mask Magazine, January 2018, http://www.maskmagazine.com/the-refuse-issue/struggle/no-lite.

- Molly Stuart, Facebook, November 6, 2018,https://www.facebook.com/molly.stuart.587/posts/2172352679689773.

- Montgomery and bergman, Joyful Militancy, 31.