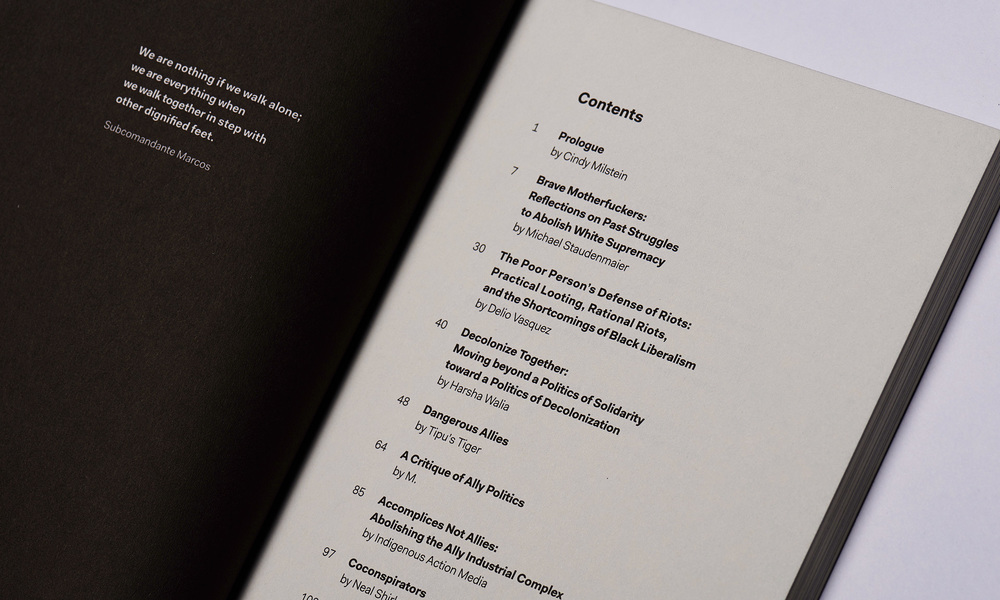

Here is a response to Arun Gupta’s review of Taking Sides. It is written by Michael Staudenmaier, author of Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969–1986 (AK Press, 2012). Michael wrote an original essay, “Brave Motherfuckers: Reflections on Past Struggles to Abolish White Supremacy” that opens and introduces Taking Sides: Revolutionary Solidarity and the Poverty of Liberalism (AK Press, 2015). This is the type of discussion we were hoping would be generated by Arun Gupta’s review. We encourage you to continue the discussion in the comments section. Perspectives Eds.

Early on in Arun Gupta’s review of Taking Sides, “A War of All Against All,” which appeared here in Perspectives, he writes, “The exact purpose of the book is hard to glean, other than gushing white-hot rage.” Replace “book” with “review” and you have an apt description of his essay. It is clear that Taking Sides made Gupta angry, but it is not at all clear why. Nor does he offer much of an alternative framing for a set of issues he acknowledges are important.

Instead, Gupta labels the book “hectoring;” says it is characterized by a “lack of rigor;” full of a “parade of clichés” and a “stew of overwrought drama, self-parody, and triteness.” It is a “jargon salad” and “astonishingly sloppy.” His piece tends to mock rather than meaningfully engage with the ideas in the book. Critical reviews are, of course, exactly what all of us who contributed to Taking Sides have hoped to see, but Gupta’s essay seems dangerously close to being an argument in bad faith.

Words

I eventually came to read Gupta’s review as an extended exercise in psychological projection. He is particularly incensed that the contributing authors in Taking Sides are “fixated on linguistic purity,” or in my case, characterized by an “obsession with language.” This seems ironic coming from the guy who offers a paragraph long definition of identity politics, and then proceeds to criticize multiple authors because they (we) fail to define their (our) own terms with similar “rigor.”

For whatever it’s worth, Gupta apparently dislikes my essay less than most of the others; he even calls it “useful.” Compliments aside, I am confused how he decided his main takeaway from my piece was that my “beef with allyship is semantic.” I don’t spend a lot of time on words themselves, apart from a passing reference to Steve D’Arcy’s essay on the topic. I’m actually much more interested in the idea that “people in struggle disagree with each other, and those disagreements can change the world.” (9) But you won’t learn that from Gupta’s essay. It would seem that his “beef” with my piece is pretty semantic itself.

Ethics

At the end of the review, his projection becomes even more extreme: “Taking Sides sows distrust, creates divisions, and encourages self-righteousness.” I read Gupta’s essay as deeply self-righteous, and he’s clearly hoping to generate distrust.

Take, for instance, the claim that Cindy Milstein’s essay criticizes a prominent Bay Area activist without naming him. In itself, there doesn’t seem to be anything objectionable about such behavior, but Gupta asserts without explanation that it is “unethical, irresponsible, and antithetical to solidarity.”

Gupta’s claim is so vague and his charge is so extreme that readers might easily assume – as indeed I did initially – that he was accusing the author of snitching or otherwise jeopardizing the safety of the person in question. I now understand, via private clarifications from a Perspectives editor, that the entirety of the claim is that the person in question is identifiable based on context but is not named. Apparently, no claim is to be inferred that the person in question was harmed in any way by the description of him in Taking Sides. In light of this new information, the charge seems, at the very least, petty and obviously overstated.

Things then get even worse when Gupta goes on to claim that this allegedly unethical behavior is “typical of the book.” This would appear to imply that the rest of us contributing authors are guilty of having written (and AK Press is culpable for having published) comparably unethical or potentially dangerous things. But Gupta offers no evidence to support this. If he believes it to be true, why doesn’t he mention other examples? In their absence, what makes the singular example “typical”? Not only is the case in question argued badly, but the breadth of the characterization is itself ethically questionable.

People

Gupta rails against “astonishingly sloppy” argumentation in Taking Sides. But then we come across this: “This book assumes readers are familiar with these ideas and how they operate. If that’s true, then there would be no need for basic organizing tips.” This assertion does not follow logically, and it has not been borne out in my limited personal experience. In the aftermath of both Occupy and Black Lives Matter, it is clear that at least tens of thousands of people have been activated politically. Many have some limited familiarity with the general rhetoric of various movements, while remaining relative novices who might benefit from “basic” suggestions and critical analysis.

I met dozens of people like this in the aftermath of Occupy when I toured with my book Truth and Revolution during the spring and summer of 2012. And today I know dozens more, just in Chicago alone. These are people who have been mobilized before, during and after multiple local crises and are looking to rethink and clarify their organizing approaches.

I don’t live in a hot-bed of “smashy-smashy,” and no rioting took place after the Laquan McDonald Chicago police murder video was released. And yet lots of people here, from squatters to undocumented anti-ICE organizers to left-wing aldermanic (city council) candidates, still seem to find something of value in Taking Sides. Whatever their disagreements with various essays, they don’t appear to feel like victims of a “circular firing squad” for failing to embrace “would-be insurrectionists.”

Politics

Perspectives on Anarchist Theory asked Gupta to review Taking Sides, hoping to initiate “debate and constructive engagement” about the issues in the book. His commitment to “constructive engagement” is in extreme doubt, however, and there is also no indication of anarchist politics to be found in the review itself.

In its place, there is a distressing liberalism at the core of his critique. His closing anecdote about an encounter between Occupy veterans and steelworkers is telling: the hero of the story is a “local labor organizer,” whose intervention is to paper over real political disputes rather than work through them. Gupta approvingly notes that she “steered the conversation back to unions” to avoid any conflict over divisive questions like school prayer.

For a very different take on the interaction between Occupy and labor unions, I would recommend reading up on the West Coast Port Shutdown and related struggles in 2011/2012. Veterans of Occupy organized with and alongside unionized longshore workers and in the process, multiple political disagreements emerged. Participants ended up challenging entrenched conservative working class ideas far more dangerous than a commitment to allowing prayer in schools. (A comprehensive introduction to the issues is here.)

If Gupta’s approach to labor struggles is liberal, his response to the urban unrest of the past few years is even more right wing. It conceives of riots as inevitable occurrences that result from a purely objective set of social conditions. Gupta’s condescending prose marginalizes both the agency and the rationality of the “undisciplined and unorganized,” the “the isolated, the powerless, and the dissatisfied.” That’s quite a large category in the United States in 2016.

Gupta writes, “It is simple to understand why poor people riot: because they are poor, at the mercy of unaccountable cops, and an instance of police brutality galvanizes that anger.” But if riots are a “simple” result of these three ingredients put together, why don’t they happen more often? Why, for instance, weren’t there riots in the aftermath of the McDonald video’s release here in Chicago? Could it have anything to do with variations in the politics and ideology of particular groups of poor people in specific places and times?

One of the things I find especially valuable in Taking Sides is the effort of multiple writers to grapple with the unpredictable alchemy of urban unrest. I think Gupta is wrong to claim that Taking Sides evinces “barely a whiff of curiosity” about the outcomes of riots, but he himself seems supremely uninterested in the actual perspectives of people who end up in the streets.

Instead, Gupta draws on a handful of academics to refute what he sees as the theory of riots purportedly advanced – “uniformly,” no less – by the contributing authors in Taking Sides. He seems to think we (all of us!) believe that radical Black organizations should be lauded because they can and do lead riots like those in Oakland, Ferguson, and Baltimore.

I won’t claim to speak for any of the other contributors, but Gupta fundamentally misunderstands my own analysis of riots. Like him, I recognize that most “organized” radicals are less likely to participate in (much less to play leading roles in) riots. Unlike Gupta, however, I think this represents a political weakness on the part of the “organized,” which in turn is emblematic of a problem for people – like me – who advocate for radical organization. This is one manifestation of a great, unresolved dilemma of revolutionary politics over the past two centuries, the unstable dynamic between organization and spontaneity.

And yet Gupta seems to think he has figured it all out. Forget about the perspectives and ideas of the “undisciplined and unorganized” people that I met on the streets of Ferguson, he argues, and focus more on building effective movements. In my view, you can’t do the latter without the former.

Lessons

Gupta’s review isn’t a complete waste. Buried deep inside it is an insightful criticism of several of the essays in Taking Sides: “While many authors legitimately argue one shouldn’t trust someone who claims that their identity gives them unique insights, the writers commit the same sin.” I flagged this as a concern when I read the draft manuscript. But I also recognize that it’s a difficult question, one that several pieces in Taking Sides grapple with in different ways. Part of the point of my essay was to provide a historical reminder that movements can’t wish themselves magically past the sort of political impasses identity politics and allyship have created over the past couple decades. To move through and beyond them requires argument and struggle.

What I like about Taking Sides, as I said in my original introductory essay, is that its various pieces help remind us how “people’s consciousness shifts rapidly in the course of intense periods of activity” (9). While I have many disagreements with many of the essays in the book, I remain impressed by the collective willingness of the authors to interrogate their (our) own experiences and try to draw lessons from them.

I’ve seen the impact in action here in the Midwest. In Chicago, a number of organizers have spent significant time reading and discussing the pros and cons of the various essays, how they resonate (or don’t) with their experiences in social movements, and how they might shape future efforts. Through comrades, I’ve heard similar stories from Minneapolis, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and elsewhere. If there were a how-to manual for the use of Taking Sides, this would be the model – critical engagement in the context of struggle. Gupta’s review essay, by contrast, seems more interested in scoring points. That’s a shame.

Michael Staudenmaier is a longtime anarchist organizer and a historian of race and ethnicity in the Americas, with a focus on the role of grassroots social movements in the construction of Latina/o identity. He just received his PhD. in history from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and is the author of Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969–1986 (AK Press, 2012). He lives with his wife and three children in Chicago.