A friend of mine, a Trump supporter, recently sent me a social media post from an anonymous Seattle police officer about the “organized protest” zone, or autonomous zone, established by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the city’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. The officer argues, in part, that “there is a part of our country that is no longer under our control,” and that “we [the police] have been castrated.” The post is mostly filed with misinformation, that the protest space has its own currency, ID system, and that the former police precinct, abandoned by the mayor and the city at the height of the protests, is being used as a BLM headquarters – no doubt a kind of black witches coven in their imagination. Indeed, in the language used in the post, “terrorists” and “anarchists” are stock piling “ammo and chemical weapons,” and are headed by a “warlord” who “drives a tesla and has been arrested for drugs, guns, pimping and crimes against children.” The officer concludes that “this is real,” and that “you can’t make this up.” These developments they call “unthinkable.”

The police are not the only ones hysterical at the loss of their station. Right wing media have also chimed in, exacerbating and stoking the fears of the Right. Fox media personality, Tucker Carlson, for example, bloviates on his nightly show that the founders of the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP) are “just like the conquistadors” because they’ve seized and occupied already established land and are extorting local businesses. Not to be outdone, President Trump, searching for an election year issue, called on the city of Seattle to attack and retake the space. He tweeted angerly, “Take back your city NOW. If you don’t do it, I will. This is not a game. These ugly Anarchists must be stopped IMMEDIATELY.”

What is unthinkable, or was at the beginning of the month, is the power of the Black Lives Matter movement in the streets. The emergence of the autonomous zone is a pinnacle of that power, a significant victory. It demonstrates the ability of popular power to win the impossible from structures of white supremacy – the state and the propertied interests they represent. That victory, and the subsequent diminution of state violence, is a major step forward for community self-control and autonomy. It shows that ending anti-Black violence is the first and most basic step to honoring Black life.

But it is just the beginning. Honoring Black life means constructing a society where Black autonomy and Black power are the cornerstones of community, and one where Black freedom is the foundation for broader, collective liberation. The advent of the movement’s autonomous zone was a step in that direction. Taking the city’s east police precinct demonstrates not only that our movements can win, but we can win previously unimaginable victories for Black lives.

There is another legacy now that must be dealt with from the CHOP. Much uglier, it is about the violence that took one life and left several in critical condition in a series of recent shootings. The shootings and the lack of direction for the space sadly demonstrate that our movements are not yet mature enough to know what to do with victory. As I write, the Seattle police are threatening to retake the building in the wake of the violence.

The shootings happened as the movement languished. With no clear direction, political, strategic, and tactical infighting broke out, reminiscent of Occupy Wall Street’s failures. Questions emerged over whether the encampment was for abolition or reform, taking the police station or not, “autonomy” or remaking existing institutions, marching or occupying, and others. This infighting was rooted in a lack of decision-making process that made even the most basic agreements impossible to gain collective consent.

In the autonomous zone, a diverse flowering of self-activity emerged, a variegated patchwork of mutual aid projects, support, care, and action that reflected the full diversity of the movement’s politics and people. That beautiful moment must not be lost in its downfall, but now with violence in the space, it must also be held within a more complex picture of the movement’s failures as well.

First, the victory

Having the city abandon the precinct was a huge victory for the Black freedom movement in Seattle. It came after weeks of fierce clashes with police. The weekend after the murder of George Floyd saw confrontational and angry downtown riots that burned police vehicles, broke store windows, and looted merchandise. Quickly, a city curfew was imposed. Instead of dying, the protests turned into even larger mobilizations across the city and the region, even in small, mostly white bedroom communities.

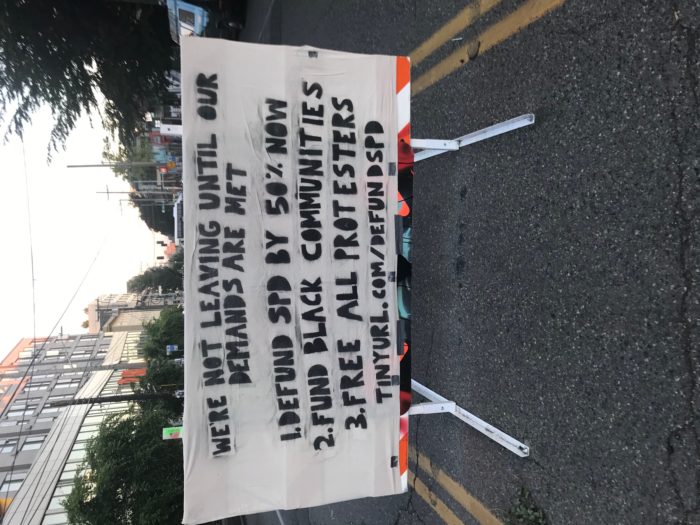

Tens of thousands of people marched. On Wednesday, June 3rd, the sixth day of protests, BLM and anti-criminalization organizers from Block the Bunker, No New Youth Jail, and Decriminalize Seattle issued a series of simple and direct demands to the mayor and marched with tens of thousands to City Hall. They helped establish the goals of the protests as 1) cutting the city police budget 50%, 2) refunding community needs, and 3) releasing those arrested during protests. This marked a huge advance for the movement; the protests now had clear, ambitious demands.

The action at City Hall also put the crosshairs squarely on Mayor Jenny Durkan, with increasing calls for her resignation. The demonstrations continued throughout the week, high school students formed impromptu marches that turned into street occupations. Actions of thousands popped up in unexpected parts of the city, like the mostly white, and affluent northern sector. In the Othello neighborhood, a poorer and Blacker part of the city, organizers filled Othello park with thousands, fists in the air, chanting “Black Lives Matter.”

Meanwhile, in Capitol Hill, nightly clashes with the police were escalating. Every evening thousands gathered at police barricades constructed to protect the east police precinct building. These actions came on news that Minneapolis had burned to the ground one of their police stations. Overwhelmed, outnumbered, and exhausted, police used aggressive tactics, often charging into the crowd to push back the throngs of protestors. One young woman was hospitalized, her heart stopped after getting hit the chest with an exploding flash-bang grenade. Tear gas stung the air until one or two in the morning. This continued night after night.

Momentum, Power

Widely criticized for the aggressive approach the police took, in which child protestors were maced by riot cops, and other protestors tackled and beaten, the mayor was under intense scrutiny, and seeming to lose control over the situation. On Friday, June 5th Mayor Durkan promised a 30-day moratorium on the use of tear gas. But the very next night the police again gassed people in the streets protesting. City council members announced calls for the mayor to resign, and began drafting official statements. On Sunday, protestors continued to gain power, as the situation further spiraled out of the mayor’s control. That evening, a young man, and relative of a Seattle police officer, drove his car into the protest, shot one man in the arm, before surrendering to police lines. At the same time, President Trump was stoking the Right to shoot “looters” in the streets.

Then the bombshell. In a surprise announcement on Monday, June 8th, Chief Carmen Best said the police would vacate the precinct at the center of the Capital Hill protests. On Twitter moving vans were seen removing equipment from the station. The withdrawal was a huge victory for the movement, and likely saved Durkan’s position as mayor, for a time.

That night demonstrators again gathered at the station, this time coming right up to the walls of the building. Uncertain what to do, and fearing a trap, BLM demonstrators did not occupy the station. Rumors that armed gangs of Proud Boys were ready to attack demonstrators, possibly circulated by the police, led to people seeking to protect the area around the east precinct. Late in the night on June 8th demonstrators declared the area a police-free autonomous zone. By the next day, hundreds rushed into the space to establish an infrastructure of occupation that allowed residents and protestors to stay, and kept the violence of the police out.

Instantly the character of the neighborhood transformed. From a space filled with nightly clashes punctuated by police violence, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) as it was initially called, demonstrated a flowering of art, mutual aid, music, direct democracy, and self-sufficiency. Without the violence of the police, people organized their lives and their neighborhood in ways that suited their interests and priorities. These were all humane, focused on defending and honoring Black life; many were quite beautiful.

The toppling of the east precinct was a huge victory. Not only because it demonstrated that people had the power in the streets to oust the mayor, and beat back police violence, but because it opened the horizon as to what kind of neighborhood, city, and society we could create and live in.

No Direction

The victory of the CHAZ soon came to be undone by the lack of political maturity of the movement to capitalize on victory. This is not about unity, but maturity: the ability to navigate political difference and move forward on shared interests for collective liberation. Indeed, as soon became clear, there was little ability to discuss the pressing strategic and logistical concerns in the space.

Instead, people just started doing – hundreds and thousands of people working on hundreds of individual and collective projects. This included a community garden for Black and Indigenous lives, nightly concerts and political rallies, documentary film screenings, a veritable renaissance of street art, a “decolonial” café, and more. For the movement, there were nightly marches to other police precincts, and people used the autonomous zone for meetings, political conversations, popular education, and abolition work.

Even in the early days of the zone however, there were problems evident. The biggest was that there was no space to have collective decision making to shape agreed upon priorities. A general assembly did emerge, but it was very difficult to get things done. It became more of a speak-out, with people voicing impassioned testimonials against the police, but not able to raise political or strategic questions with each other. This was partially because few had experience facilitating large meetings, forming agendas, setting short time limits for debate, and having the discipline to silence or remove those who were off topic and disruptive. This was exacerbated by police infiltrators who acted to divert, distract, and make focused conversation more difficult.

In addition, there were significant political differences difficult to overcome. Changing the name from CHAZ to CHOP – Capitol Hill Organized Protest – was reflective of this. Very early, there were voices raised that the autonomous zone was a distraction, that it took away from the movement for Black lives, that the focus became holding space, rather than stopping police violence, and that it was dominated by white activists. There are merits to these claims. Still other voices, many of them Black, questioned the focus on “autonomy,” arguing that as African Americans they sought not autonomy from the institutions of the country, but integration, respect, and a dignified existence within. Again, with merit.

There were differences between Black voices, and for white ally politics this posed a quandary – whose voices to prioritize?Some Black and POC organizers were talking with the police, making suggestions to lead marches away from the zone, or to make other concessions with the cops including allowing street traffic access or in other ways limiting and restricting the autonomous zone. While other Black voices were more militant, defended the notion of an autonomous zone, and challenged the more conservative Black organizers. Others were frustrated by the whole debate over the name and looked for a clearer strategic orientation for what to do with the precinct, the autonomous zone, and what could be won from the police. Part of this confusion was also because most of the established radical Black leadership was organizing elsewhere, putting their efforts into other mobilizations in the city.

Then people started shooting. On Juneteenth one man died after a fight in the CHOP. The next night there was another. And a few days later, yet another still. Several people were sent to the hospital in critical condition. While one victim said his assailants were white supremacists who were lurking near the space, most of the shootings stemmed from internal personal conflicts that spiraled into violence.

In the most recent days, Mayor Durkan and Chief Best have done their darndest to capitalize on the situation, calling for the occupants to voluntarily leave, marshalling conservative Black leadership for support, and waiting for people to disperse enough to get the precinct back. These are tense and troubling moments. Meanwhile, people in the zone cannot agree on strategy at this critical juncture. Some are arguing in favor of leaving, others, for holding the space at all costs.

How to Castrate a Bull

The fact that the police express feeling “castrated” with the victory of the movements for Black lives, underscores the synthesis of racism, patriarchy, violence, and state power. The police, the president, and the Far Right loath the loss of the precinct and the creation of the organized protest space because it is a significant defeat of their power, their values, their way of life. In the words of one Seattle police officer, they’ve lost control of their own country.

Their defeat is our victory.

The emergence of the autonomous zone shows that the limits of what mass movements can accomplish are shaped only by the limits of our power in the streets, and the limits of our imaginations for what is possible. The collective and humane values expressed in the zone are cause for celebration, a source of beauty. Black life can be honored when the institutions of white supremacy, like the police, are not reformed, but removed. In their absence we can create a space where Black voices are honored, where Black life truly matters.

But the legacy of the organized protest zone is more complicated than a simple and straightforward celebration. The emergence of violence in the space is a gift to the Right. They can argue that policing is necessary and that the excesses of movements must be checked.

For us, the failures demonstrate that basic meeting facilitation, lack of ability to engage with complication and complexity, and allowing for difference while working on projects of shared interest are very serious shortcomings that require quick resolution. Further, it reveals that politics are important. The ideas and visions we have in our heads are what enable us to set future horizons of freedom.

Thankfully, there is much more movement in front of us, and whatever happens to the autonomous zone, the movement for Black lives can push forward in a multitude of directions. We’ve already seen it here in Seattle. In the last week the police union has been ousted from the labor council. Armed police have been forbidden from schools. Police budgets will be cut and their use of an array of weapons banned. We must act to create sites free of police violence in the other institutions and zones of the city. We can build from one autonomous zone, to many. Even if the CHOP dies, autonomy continues to grow.

Michael Reagan is a historian and activist in Seattle. He is the author of the forthcoming Intersectional Class Struggle: Theory and Practice to be published by the IAS and AK press. Find him on Twitter at @reaganrevoltion

If you like this essay, please support our work here: https://anarchiststudies.org/support-the-ias/