Some days I feel like I know what needs to happen. I imagine we can dream a way past capitalism, a way to unify efforts to eradicate oppression, a way to develop power-sharing processes and create balance without enormous loss of life or slipping into another revolution of action/reaction. I imagine we can find a way to recreate the concept of democracy, to retain the tensions and pleasures of gender while abolishing its strictures and demands, to render race a null concept, an obsolete and murderous idea left in the past. Whether these things are happening or not is another story, but I hold tightly to my small projects and big dreams. I work to read and remember the lessons of past generations. I carry forward the ideas and principles that inspire me and others like me, those dedicated to being discontent with corrupt power, those who chase elusive ideals of freedom and equality. Some days, everything feels possible.

Other days, I feel pessimistic, beyond powerless—I feel blank. The entropy of the system overwhelms my ideals, and I find it difficult to see past the moment in which we find ourselves. Some days I can’t imagine how we will make the world any better. The problems we face feel simply too convoluted, too entrenched, too exhausting to solve. Where do we start? How will we know when we’ve found the answers we need?

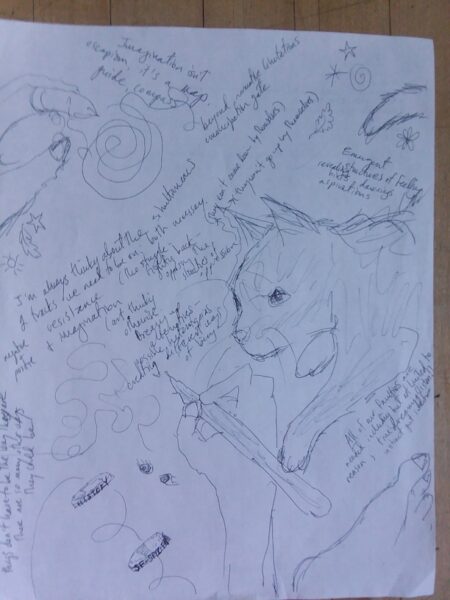

Some psychologists divide problem-solving into two types of approach: convergent and divergent thinking. Convergent thinking is the kind that follows a series of tried-and-true processes or steps and results in one answer. If reasoning is based on convergent principles, it is assumed that anyone who works on the problem will reach similar conclusions, as with arithmetic or simple logic puzzles. Some kinds of organizing rely upon this approach—do X and Y, and Z will result. Efforts like canvassing and other forms of educational outreach often seem to be based upon these assumptions, for example. Divergent thinking, on the other hand, takes no part of the problem for granted. Any puzzle is assumed to have multiple possible solutions, multiple processes for reaching them, and even multiple approaches to the nature of the problem, itself. Divergent thinking is generative, critical, and creative; it is more than just thinking outside the box—it questions whether the box is necessarily there at all, or if the box even needs to be addressed. It finds other ways to perceive the problem and takes risks to generate ideas and options. Even if the solutions this kind of thinking arrives at don’t always work, they provide insights and happy accidents that couldn’t have happened through time-tested approaches.

Convergent and divergent thinking both play valuable roles. They allow us to use the lessons learned in the past and also to recognize when we are in uncharted territory. Convergent processes can be a form of wisdom transmission. We know we need to learn our history so that we can recognize when patterns repeat themselves, as with the rise of fascism, or celebrate victories and draw strength from the courage of our predecessors, as with the martyrs, prisoners, and resistors from the movements in the past that light our path. Following the processes and procedures we have learned from our elders and mentors can save us from reliving similar mistakes and grant us perspective when our vision narrows to the present moment’s failures or successes. Yet many aspects of our work change quickly, like street tactics or language; others are met with exceptional challenges, like changes in information technologies, surveillance, or global climate change. As political and social circumstances and contexts change, we are at our best when we are flexible and able to shift and adapt. What are the structures we can build, the values we can encourage, that allow for these qualities to emerge?

We may be in unprecedented territory—and if we aren’t, we still may not be able to get out of here the same ways we got in. Now is a time for courageous imagination, for risking new and untested methods, for allowing our minds to fire and associate freely, and for relying on the darker wisdom of the subconscious. The collective dreaming and deep creativity that drive our connections may be the new tools we need to engage. In this issue, you will find games, pleasures, dancing, and nightmares—new ways to look at the moment in which we find ourselves, and new approaches to build the world we want.

We want a world we can live in with our whole selves—that means bringing the stories and the dreams with us. We can learn from fiction as well as from data; empathy, insight, truth can be found beyond academic forms. We have included fiction and poetry in this issue, as well as essays, investigations, and reviews in an effort to imagine a fuller sense of freedom and the ways it can be expressed, envisioned, and shared. It is time to encourage our approaches to diverge so that we can meet up again further down a road, perhaps in a terrain we can’t yet imagine.

The Imaginations issue of Perspectives (n.31) is available from Powell’s Books here! and AK Press here!

******************************

A tip of the hat for the Imaginations issue to: Charles Overbeck at Eberhardt Press; Lantz Arroyo of Radix Media; Roger Peet, Josh MacPhee, and all the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative artists featured in this issue; the IAS board & our outstanding admin Sara Libby; Amanda Priebe; all the authors who contributed; everyone who has ever donated on-line, with a check, or at an event to the IAS, which helps make Perspectives possible; all our pals at AK Press; Kevin Sampsell at Powell’s Books; and everyone fighting for and striving to create a better world.

Perspectives’ collective for the Imaginations issue (n. 31): Maia Ramnath, Lara Messersmith-Glavin, Paul Messersmith-Glavin, James Birmingham, Sara Rahnoma-Galindo