This piece originally appears in issue N. 28 of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, available from AK Press.

“I will carry my soul in my hand

/ And throw it in the valleys of death /

It is either a life that makes a friend happy

/ Or a death that makes an enemy angry.” –Abdulrahim Mahmoud, Palestine

“When the will is free and the cause is just, and you embody both, the human is capable of making miracles happen, and no oppressive, tyrannical, murderous regime can harm it” -Ameer Makhoul, Palestine

“Sometimes I sit in the chair and vomit. Nobody says anything. Even if they turned their backs I would understand. I’m looking for humans. All I ask for is basic human rights.” –Emad Hassan, Guantánamo Bay

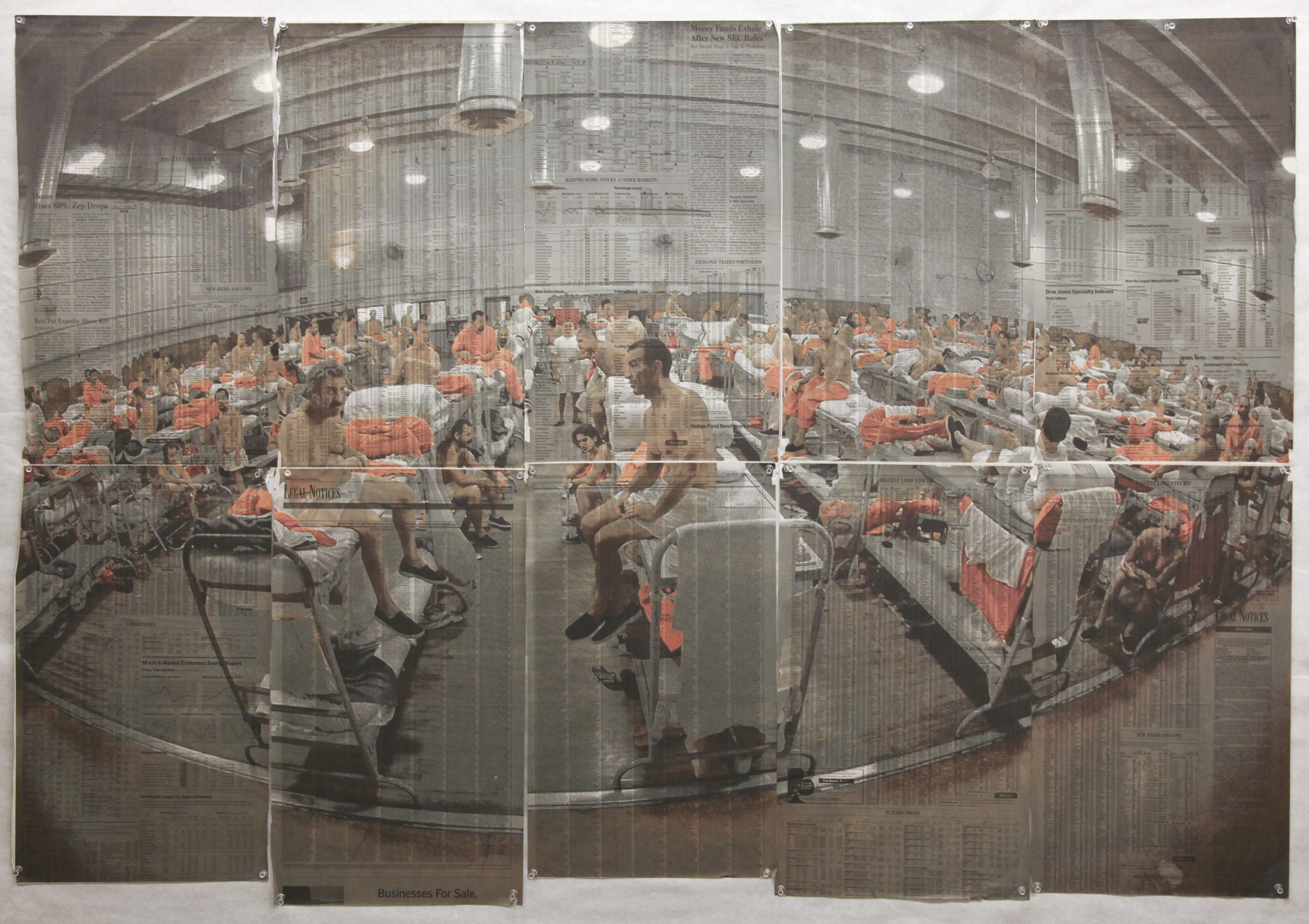

(Photo by Max Collins)

Detained at Guantánamo Bay, Adnan Latif, a Yemeni who was sold to US forces for a bounty, undertook a series of hunger strikes after three years of isolation and torture. Although cleared for release in 2009, like nearly all fifty-six Yemeni detainees there, he still saw no end to this living death in sight. He, like many others at Guantánamo, saw his hunger strike as a way to redress injustices, intervene politically, and take back some small shred of agency. His writings reveal mixed motivations—sometimes determination, sometimes desperation, but always colored with deep pain. He wrote in a letter to his attorney in 2008:

“Anybody who is able to die will be able to achieve happiness for himself, he has no other hope except that. The requirement is to announce the end, and challenge the self love for life and the soul that insists to end it all and leave this life which is no longer anymore called a life, instead it itself has become death and renewable torture. Ending it is a mercy and happiness for this soul…I will do whatever I am able to do to rid myself of the imposed death on me at any moment of this prison.”[1]

Latif’s plea speaks to the collapsed distinctions between life and death he experienced at Guantánamo, physically alive but sustained in a space more accurately understood as a living death. Each time he began a hunger strike, he was demanding to be either charged or released. And each time, he was force fed twice a day, a process he described as “having a dagger shoved down your throat.”[2] Despite being cleared for release, having undertaken a hunger strike in 2007, and deteriorating in terms of mental and physical health, Latif’s demands continued to go unaddressed. On September 8, 2012, he was found dead in his cell. The US government claims he committed suicide.

In May 2013, six months after Latif’s suicide, over one hundred inmates at Guantánamo began the prison’s largest hunger strike. Of the hunger strikers, eighty-six had been cleared for release, some of them for up to six years, yet they remain.[3]

But this isn’t the beginning of the story. There have been numerous documented hunger strikes at the military prison since 2005, some of them lasting for years. Samir Naji al-Hasan, one of the inmates who participated in the hunger strike in 2013, stated simply, “There is no end in sight to our imprisonment. Denying ourselves food and risking death every day is the choice we have made.”[4]

As this is written, waves of ongoing hunger strikes are being carried out, a struggle which seeks to transform a space of confinement and erasure into one of imagination and rebellion. From Guantánamo Bay, Cuba to Pelican Bay, California, and ADX Florence to Palestine, hunger-striking prisoners are exploring and proving a space of resistance, refusing food in the face of inhumane and indefinite detention. Some hunger strikes have been publicized; others have not. But despite the distance, motivations, and circumstances of these collective actions, their purposes ring true: they are starving for the sake of dignity.[5] In an arena in which dehumanization is both the purpose and the product, the hunger strike is a reclamation of humanity and agency, and a statement that to live freely—not simply to live—is something worth risking life for.

Prisons have become a new type of battleground for modern democratic nations. Especially since the onset of the “War on Terror,” incarceration has been fundamental to the US, which Israel has expressly shared. Particularly for the purpose of what Laleh Khalili terms confinement in counterinsurgency, the US has built and established black site prisons, proxy prisons, military prisons, federal detention centers and even a military prison ship that floats in international waters so as to be unbound by the laws of any nation. In these sites, countless individuals—almost entirely Arab or Muslim men who have been deemed “terrorists” or “enemy combatants”—are held in a space of non-being where nothing is certain but simultaneous pain and erasure.[6]

It is in this context that we find ourselves witnessing a new type of battle—one in which the state wages war to keep bodies alive, and behind bars, and in which these incarcerated men risk death in order to live, attempting to reclaim dignity and self-determination. As Moazzam Begg, former Guantánamo inmate and hunger striker stated poignantly in his memoir, “Much of mankind has chosen life as a path to death. But I have chosen death as a path to life.”[7]

Emad Hassan, a Yemeni man who has been incarcerated at Guantánamo and has been on permanent hunger strike since 2007, has been force fed over 5,000 times. He, more than most, knows the deep trauma this brings. The physical and psychological impact of 5,000 feedings is incomprehensible. One’s relationship to food and being fed changes: the food becomes a weapon forced upon a body through a medical procedure that is simultaneously painful, torturous, and psychically breaking.

How can we understand what is happening in places like Guantánamo, where individuals are expressly not killed, and in fact, great and expensive lengths are taken to maintain the life of their bodies despite mass protests by the prisoners and, in some cases, public outrage. Taking from Agamben’s Homo sacer and his discussions of “bare life,” as well as from Foucault’s concept of “biopolitics” and Mbembe’s reformulation of it as “necropolitics,” here we examine the relationship between “bare life” and sovereignty through the site of prisons operated by or in the US and Israel. However, we depart from Agamben, and join E.P. Ziarek, in asserting bare life as “complex, contested terrain in which new forms of domination, dependence, and emancipatory struggles can emerge,” containing within it the possibilities for rebellion and radical transformation—perhaps, not so bare.[8] We seek to demonstrate how bare life contains the possibility of rebellion within it.

“Freedom” is a desire that is simultaneously political, physical, ideological, metaphysical, and rebellious. Many prisoners’ words are translated from the original Arabic, which does not linguistically distinguish between more liberal concepts of “freedom” as existing within the law, and “emancipation,” which implies freedom from it. Here it is understood as rebellion embodied in the form of the hunger strike, reclaiming and asserting ones’ individual sovereignty vis-à-vis the body despite every attempt by the state to control it.

Liberal Warfare and Guantánamo Bay

In Time in the Shadows: Confinement and Counterinsurgency, Laleh Khalili traces a shift in techniques of warfare and population control, delineating the particularities that have arisen in modern liberal warfare, characterized by a performative aversion to violence, particularly since the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Khalili locates this shift primarily as one from reliance upon mass slaughter towards means of control marked by techniques of confinement: confinement was established and developed as an alternative to slaughter. Battlefields gave way to prisons, and the spectacle of death was transformed into sophisticated and sprawling designs of social control and incarceration. [9] Rather than destroying the physical enemy himself, modern liberal warfare seeks to confine and lever the body in the project of breaking and making a subject.

In the prison, individuals and their bodies are maintained in a state that Agamben calls “bare life”[10]— in which one is exposed to violence and, as both a precursor and result, divested of political subjectivity.[11] One is carefully maintained in a state of living death, kept alive but only at the most minimal level. With the use of confinement to produce bare life, the sovereign seeks explicitly to break and reshape subjects, subjecting individuals to a continuous process of detachment and reconstitution until the “perfect subject”—i.e. a fully broken being—emerges.[12]

Many have argued that sovereign power is based in the right to determine the conditions of life and death, a concept that has been called “biopower.” Michel Foucault argued that the mechanisms of biopower, which include the sovereign’s exclusive right to kill, are fundamentally inscribed in the way all modern states function. This process of dividing subjects into those who must live and those who must die is the domain that establishes the political realm of the sovereign.

Achille Mbembe takes the relationship between the state and the body a step further, locating it entirely in the power to determine what bodies may and should die. Rather than placing the possibilities of power in individual life, Mbembe argues that to exercise sovereignty is “to exercise control over mortality and to define life as the deployment and manifestation of power.”[13] Thus for Mbembe, the process of extending sovereignty is a constant making and remaking of the conditions in which death may be unconditionally exercised, a process he terms necropolitics. Thus, through the monopoly over the right to kill, the total apprehension of the body, the state obtains its power.

Guantánamo Bay prison camp has become one of the most contested and egregious examples of confinement in counterinsurgency, termed by Khalili “liberal carceral confinement taken to its logical conclusion.” At Guantánamo Bay, the necropolitical nightmare becomes a grotesque reality.[14]

Guantanamo

Guantánamo Bay was occupied by the US in 1898, and the US has retained a perpetual lease from Cuba since 1903.[15] During the Haitian refugee crisis in 1991, it was used for the confinement of Haitian civilians, held in cages of barbed wire under the stigma of AIDS. Techniques of segregation, isolation, ghettoization, and confinement were practiced on this population, and the structures that supported these processes eventually became the foundation of the modern-day prison complex, which is still comprised largely of tents, cages, and barbed wire.[16]

Since the onset of the “War on Terror,” Guantánamo Bay has been utilized exclusively for the long-term confinement and isolation of Muslims accused of having connections to terrorism, classified legally as “enemy combatants.” Though very few inmates were indeed accused and found guilty of participation in terrorist attacks—for instance, the infamous Khalid Sheikh Mohammed—most were retained for reasons that remain complex and unclear.

Many inmates held at Guantánamo were originally presented as being sources of information. However, the reality is that some ninety-two percent of inmates held at Guantánamo were not al-Qaeda fighters.[17] Critically, a large number were sold to the American forces in Pakistan or Afghanistan for a monetary reward, regardless of their relevance to the war.[18] Other men were picked up based on hearsay, having been “tipped off” by another seeking revenge or reward. As noted in a report published by the Center for Constitutional Rights, the US government’s payment of cash bounties in the early stages of the war created an indiscriminate dragnet in Afghanistan and elsewhere that resulted in the detention of thousands of people, many of whom had no connection to Al Qaeda or the Taliban and/or posed no threat to US security.[19]

In the aftermath of 9/11 at least 1,200 people inside the US, mostly Arab, South Asian and Muslim were arrested, confined, and sometimes deported despite the fact that none was ever charged with a connection to the attacks.[20] As one military guard at Guantánamo said to inmate Moazzam Begg, “In the US they have always hated black people, but never feared them. During the Cold War, they feared the Soviets, but never hated them. With the Muslim world, they fear you and hate you.”[21]

A History of Anti-Blackness

Contrary to the views of this prison guard, the US has been afraid of Black populations—and deeply so. In the 1960s and 1970s, the mainland US saw what was perhaps the height of this fear, with the rise of revolutionary liberation organizations such as the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army, and the MOVE Organization.[22] Confronted with these organizations, who fought for racial justice and advocated self-defense against hostile and invasive government agencies, the US government concocted illegal plans to surveil, arrest, imprison, and sometimes kill members who were deemed the nation’s “greatest threat to national security.”[23] This follows a long and sordid history in which the US criminal justice system has been used to punish dissent and contain unwanted populations. The history of US policing and the “neutralization” of these organizations is a stark testament to the US pattern of political imprisonment and murder of racial others.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the US established a series of Behavioral Modification Units (BMU’s; these have also been referred to as Control Management Units and Special Housing Units). Predominantly targeting Black Muslims—the population deemed the “most dangerous black extremist group in the United States” at the time—these BMU’s experimented with new techniques of sensory deprivation, physical abuse, long term isolation, and “re-education” in order to produce “de-radicalized” subjects who would not pose a threat to the American social and political order, as well as to provide a testing ground for future counterinsurgency.[24]

Since the onset of the “War on Terror,” Arabs and Muslims have become the favorite racial other to be subjected to confinement techniques.[25] In order to accommodate its ever changing needs, the US Federal Bureau of Prisons built two Communications Management Units (CMU’s) under a veil of secrecy in 2006 and 2008 for the expressed purpose of isolating and segregating certain (read: political) prisoners from the rest of the prison population. CMUs are marked by a near total restriction on communication with the outside world. Inmates are held in complete isolation, physical contact between visitors is banned, and phone calls and letter correspondences are severely limited. Despite making up only 6% of the federal prison population, Muslims comprise eighty percent of CMUs.[26]

In the twelve years that followed 9/11, there have been over 500 federal prosecutions of Muslims. Even more disconcerting, over 80 “terror-related” suspects have been detained right in the belly of the beast itself, at the Manhattan Correctional Center in New York City. The MCC sits nestled between rows of Thai restaurants, yoga studios, and jail bond merchants. Oussama Kassir, accused of having attempted to set up a terrorist training camp in Oregon, began a hunger strike to protest his continued mistreatment and almost complete isolation. He was force fed in a cell in downtown Manhattan, while an entire city went about its daily business.[27]

Perhaps most notorious in detaining individuals on terror-related offences is ADX Florence, a federally run prison located in Florence, Colorado. ADX Florence has been referred to as a mainland Guantánamo Bay, where Muslim men are whisked away, out of sight, out of mind, tangled in bureaucratic procedures and yet unprotected by law. Perhaps it is for this reason that the former warden of ADX Florence affectionately dubbed it “a cleaner version of hell.” Fahad Hashmi, a Muslim man of Pakistani descent, is one of those being held in the prison’s administrative segregation unit, or H-Unit. He was transferred there after three excruciating years in solitary confinement at MCC. Guantánamo attorney Pardiss Kabriaei reminds us that torture does not have to be physical, “we have words and images to describe waterboarding; it is harder to convey the suffocation of perpetual detention…Fahad’s torture has also not been flagrant; it has been silently mind-crushing.” She continues:

“The image of Fahad’s torture is not that of a person being led around an interrogation room on a dog leash, or held in a stress position with heavy-metal music blasting. It is a person sitting still in a small cell, slowly deteriorating in a modern prison on the outskirts of a small Colorado town.”[28]

The Hunger Strikes

To My Father

I have no fellows but the Truth.

They told me to confess, but I am guiltless.

My deeds are honorable and need no apology.

They tempted me to turn away from the lofty summit of integrity,

To exchange this cage for a pleasant life.

By God, if they were to bind my body in chains,

If all Arabs were to sell their faith, I would not sell mine.

–Abdullah Thani Faris al Anazi, Guantánamo Bay

British Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone first authorized force-feeding in 1909 against British suffragettes. Up to that point, the process had primarily been practiced in insane asylums. Today, the practiced has been expanded to such a degree that, according to a report by Solitary Watch, there have been over 900 force feedings at ADX Florence’s H-Unit since the beginning of the “War on Terror” in 2001.[29]

As E.P. Ziarek and Banu Bargu have rightly noted, Agamben’s concept of bare life falls short in failing to consider the possibilities of resistance that bare life does enable. It is by looking to this recent wave of prison hunger strikes that we can push Agamben on this point and paint a picture in which certain forms of resistance in bare life actually serve to usurp sovereign control.

Bargu has undertaken extensive research on what she terms “corporeal, self-directed, and self-induced forms of political violence,” which use the body as the conduit of resistance. Such acts of resistance include suicide-bombing, self-immolation, hunger strikes, and death fasts. In the case of asymmetric warfare, in which traditional weapons are unavailable to inmates we see the appearance of what Bargu calls “the weaponization of life.”[30] Problematizing the process of naming associated with these forms of violence, she does not call them “the weaponization of death,” rightly understanding death as something to be risked, but life as the ultimate motivation. This distinction is crucial, especially given the orientalist and Islamophobic assumptions that have informed mainstream opinions of Muslim resistance in asymmetric warfare as irrational, barbaric, and bloodthirsty. She states:

“Self-destructive acts use the body, but the body as conduit; the act itself comments on life, conveys the prioritization of political goals over life. These acts say, in a sense, that it is not worth living life if you cannot live according to your own politics; it is not worth living life if you are forced to live a mere existence. That is the metaphysical component and that is why I refer to these acts as the weaponization of life.”

In looking closely, we may see that by turning their imprisonment back upon the state as a weapon of resistance, a hunger striking prisoner exposes that the vague and complex relationship between bare life and sovereignty in liberal democratic regimes can ignite radical transformation. In other words, by “extending the possibility of militancy from the public sphere to prison itself, the hunger strike changes imprisonment into a new means of fighting for a cause, transforms punishment into rebellion, turns subjection into the ambiguous political agency of self-hurt.”[31]

The hunger strike is by no means a new form of resistance, particularly among prison populations and others faced with carceral warfare tactics. Though the motivations vary greatly among individuals, circumstances and nations, the “starving body secluded in prison and barred from public appearance” has often deeply disrupted state attempts at population control throughout history. On one hand, as Ziarek noted, “the private act of starvation reverses the guilty verdict” imposed upon a prisoner and transforms it into a public condemnation of the government, exposing the invisibility that prisons so deeply rely upon through actions carried out in cages. Transforming the relationships between private and public, agency and passivity, the prison hunger strike turns punishment into rebellion.

Imprisoned Palestinians know these lessons well, as they have been using hunger strikes to protest their detention in Israeli prisons for decades. According to Addameer, there have been hunger strikes on approximately 20 different occasions since 1967. There was a 22-day mass hunger strike in September 2011, another in 2012, and another in the summer of 2013.[32] Israel, like the US, has deeply relied upon prisons to control populations and produce broken subjects, and the two nations have shared techniques, technology, and even finances.

In February 2014, eleven Palestinian prisoners were on hunger strike in protest of illegal detention and prison abuses in Israeli prisons. The issue of administrative detention is a leading motivation for Palestinian hunger strikers, who are often held in solitary confinement indefinitely and without charge. Other cited causes mirror those at Guantánamo and include medical neglect, limited or no family visits, politically motivated imprisonment, solitary confinement, and torture.[33]

In 1980, three Palestinian men died as a result of force-feeding practices. In 1983, another succumbed to injuries sustained in the same way.[34] Since then, despite waves of hunger strikes in 1996, 2004, and 2008, Israel has not been able to force feed prisoners. However, in the summer of 2013, the Israeli Knesset was asked to review possibilities of reopening the use of force-feeding against hunger striking prisoners. These developments were simultaneous with the announcement that a new hunger strike was set to begin in April 2014—one to involve more than one hundred Palestinian prisoners.[35] Then, in July 2013, officials from the Israeli Medical Association flew to the US to meet with US authorities and policy makers at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health to discuss “methods of handling” hunger striking prison populations, and the difficulties of feeding an incarcerated person against his or her will.[36]

And so what does it mean, that members of the Israeli Medical Association are meeting in the US about ways to handle hunger striking inmates, a domain that seems in theory to belong to the state? In both US and Israeli prisons, we find that medical doctors in prisons are asked not to follow a code of ethics that comes from an understanding of medical science, but rather a certain military/prison code. As one Palestinian prisoners rights organization noted, “the medical doctors have been complicit in the torture of the hunger strikers…they do not abide by the Israeli Medical Association. They abide by the Israeli prison service.”[37]

Today, force-feeding is presented to the public as a medical and human rights issue, in which a moral necessity to keep hunger strikers alive is championed. Accordingly, a medicalized process is established and implemented to access prisoners’ bodies and keep them alive—in essence, medicine is used so that bodies may be captured, even in their rebellion. Guantánamo hunger striker Emad Hassan wrote in a statement released on February 20, 2014:

“It does not really need to be said, but it is a grave violation of professional ethics for doctors to participate in torture or cruel treatment. Surely health care professionals should not condone any deliberate infliction of pain and suffering on detainees? This would seem to be a fairly basic proposition.

Yet who is better than a doctor to cause excruciating pain without damaging the body? There is a wide divergence here between the morality of a doctor’s role and the reality of his actions. It is very, very sad. When a surgeon no longer uses his scalpel to cure a disease, he becomes no better than a butcher.”[38]

In Guantánamo, medical physicians have been either directly or implicitly involved in a variety of abuses, including force-feeding, and psychologists have been instrumental in inventing and monitoring interrogation and torture techniques. Guantánamo doctors find themselves having to choose between following military orders as military officers, or a code of medical ethics as doctors. In this instance, that code is the World Medical Association (WMA) in its Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikers, written after World War II and signed by medical societies from nearly one hundred countries. It states: “Forcible feeding [of mentally competent hunger strikers] is never ethically acceptable. Even if intended to benefit, feeding accompanied by threats, coercion, force or use of physical restraints is a form of inhuman and degrading treatment.”[39]

With this in mind, a group of doctors and a medical ethics professor published a statement in the New England Journal of Medicine urging Guantánamo doctors to refuse force-feeding hunger striking detainees. Citing the WMA Declaration of Malta, they determine: “Physicians can no more ethically force-feed mentally competent hunger strikers than they can ethically conduct research on competent humans without informed consent. It’s hardly revolutionary to state that physicians should act only in the best interests of their patients, with their patients’ consent. At Guantánamo, this principle is seriously threatened.”[40]

These physicians insist that hunger strikers are not attempting to commit suicide, and that such categorization is to medicalize what is in fact a political issue. They remind medical doctors that the goal of a hunger strike is not to die, but to address an injustice. And they point out the crucial fact that, in a military prison, it is a commander who issues the order to force feed a prisoner and not a doctor. The motivation is about punishment and control rather than medical goals. They conclude: “physicians who participate in this nonmedical process become weapons for maintaining prison order.”[41]

According to the information available, there has only been one case of a doctor refusing to force feed an inmate at Guantánamo, and that was in 2005. It is perhaps this reality, in which the voices asking for humanity have little or no intangible impact, and in which medical doctors look upon those “starving for dignity” as bodies divested of intention or agency—bodies to be fed—that Hassan made his heartfelt plea: I am looking for humans.

Guantánamo Standard Operating Procedure: A Life-Preserving Project

The US legal system has historically been a trusted ally to counterinsurgency and colonial efforts, allowing it to operate under an intricate veil of legalese. Based as it is upon precedents that include US colonial involvement in nearly every corner of the world, a legacy of slave patrols, and genocide of its native population, each of these encounters have been written into its laws. Thus, even that which is done under the auspices of the law is acting in adherence with laws that also legalized domination, control, violence and exploitation.[42]

Particularly since the onset of the “War on Terror,” a pattern of “intrusive surveillance, entrapment and government-instigated plots; overreaching ‘material support’ charges; the use of prolonged solitary confinement and so-called special administrative measures; classified evidence; and the criminalization of Islamic speech and association” have become common characteristics of the liberal modern state.[43] All of this has occurred under the auspices of the US legal system.

In the first paragraph of the Guantánamo Standard Operating Procedure (GTMO SOP) on Medical Management of Detainees on Hunger Strike, a 30-page manual which asserts its purpose as “to protect, preserve, and promote life,”[44] states: “just as battlefield tactics must change throughout the course of a conflict, the medical response to GTMO detainees who hunger strike has evolved with time.”[45]

Nowhere in its coldly calculated, procedural pages does it mention responding to the demands of the hunger strikers. In fact, it does not even acknowledge that the men on hunger strike may have a legitimate demand that ought to be dealt with through political and legal redress. It is simply asymmetrical warfare. As the aforementioned physicians noted, they refer to the hunger strike in contradictory terms: as a battle tactic at times, as suicidal behaviors at others, simultaneously rational and barbaric, irrational and dangerous.[46]

The SOP document defines a hunger striker as “a detainee who communicates either directly or indirectly (i.e., repeated meal refusals) his intent to undergo a hunger strike or fast as a form of protest or to demand attention.“[47] Admitting nonsuicidal intent, it continues: “Several of the current group of detainees has been hunger striking since 2005. This group of detainees has proven their determination, and their chronic malnourishment has left them physically frail. Given these conditions, options for intervention are more limited.”

This “determination” is imagined as existing in some kind of figurative black hole. The document never asks what the detainees are determined to accomplish, nor is there any discussion of context or demand. It is a military document of strategic warfare tactics that proceduralize their “treatment”—a treatment which is not that at all, but rather a “battlefield response” intended to break the strike and take the power of protest out of the detainees’ hands. By manipulating language, the authors of this document imagine themselves not to be force-feeding prisoners of war in a colony prison, but rather “enterally feeding” “enemy combatants” on a “military base.” Shaker Aamer, a British citizen who has taken a number of hunger strikes and is still held at Guantánamo Bay, responds to this inhumanity bluntly saying, “Sometimes, I stop asking myself if they are human beings.” In a conversation between former Guantánamo detainee Moazzam Begg and a guard, this dynamic became even more clear when the guard admitted to Begg: “I convince myself every day that you guys are all subhuman—agents of the Devil, so that I can do my job. Otherwise, I’d have to treat you like humans.”[48]

Formulated as a life-preserving project, the SOP contains a litany of charts to monitor body weight, administer medications, determine proper nutritional values, etc. The document specifically indicates that personal should “make reasonable efforts to obtain voluntary consent for medical treatment.” However, it continues: “When consent cannot be obtained, medical procedures that are indicated to preserve health and life shall be implemented without consent from the detainee.” Echoing Emad Hassan’s search for a human quoted in the epigraph, we might ask: what is the purpose of making a reasonable effort to obtain consent if one intends to act regardless? In more direct terms: what kind of logic pretends to rely upon the consent of a detainee to undertake a process called “force feeding?” The hunger strike is divided into six “phases,” each with a unique series of protocols including administering a variety of “infused formulations” made up of saline solutions, magnesium sulfate, folic acid, and a variety of pharmaceuticals.[49] In “phase III,” inmates are fed Boost mixed with table salt.

During the feeding, inmates have a lubricated feeding tube fed through their noses and into their stomachs, where it is confirmed to be properly located either by x-ray, or air insufflation. If they are “bite risks”—i.e., they attempt to bite either the tube or the nurses—they are fitted with bite masks over their faces through which the tubes are directly fed. Inmates are placed and/or strapped into a bed whose head “should be elevated to at least 30-45 degrees and are restrained in a single point leg restraint.” The chair restraint system being used has its own series of protocols, carefully delineated in the manual. The company that provides the “Safety Restraint Chairs” in which detainees are strapped and fed, E.R.C. Inc.,[50] advertises its product with this catch slogan: “It’s like a padded cell on wheels!”[51]

After being fed—a process that usually takes about 40 minutes—inmates are procedurally required to be placed in a “dry room.” This is in fact a cell in which the water is turned off, with a guard stationed outside. The prisoner is monitored for 40-60 minutes to ensure that he doesn’t vomit. The SOP indicates that “If the detainee vomits or attempts to induce vomiting, he will remain in the restraint chair for the entire observation time period during subsequent feedings.”[52]

Notably, the “dry room” is understood as a privilege that may be revoked. For revocation, the detainee either needs to “vomit” or “attempt to induce vomiting.” It indicates that if a prisoner vomits after his feeding, he will be strapped in a chair for up to two hours after its completion, after having the tube removed—a process that has been described by detainees as extraordinarily painful. This is a procedural requirement regardless of whether he vomits intentionally. If he does “successfully” vomit, nurses and guards are instructed that the detainee be immediately “refed.”

Force fed individuals suffer from closed nasal passages, damaged stomachs, sore and bleeding throats, ulcers, and respiratory problems. This is a result of both the continuous insertion/extraction of the feeding tubes, and the damage caused to a starving body by constantly pumping food into it. Medically speaking, the first few days of a hunger strike are the hardest because the body is still producing digestive juices which, when not used, can cause ulcers and upset stomach. Psychologically speaking, the gut contains more neurons than the brain, and trauma often manifests in the digestive system shutting down because blood moves to support only the most crucial body functions when it senses the need to fight for survival. These two factors, one would imagine, would make the need to vomit great—both physically and psychologically. At Guantánamo, what would appear to be a logical and expected response, is punished by being strapped in the same chair in which the initial trauma was carried out, only to have it repeated, the constant reliving of trauma.

Refusing to free these men, or charge them with a crime and put them through due legal process, those in power seek to maintain the physical existence of the body so that the body can continue to be located physically in the site of the prison so that the process of producing of living death, psychological breaking, and the molding of subjects can be properly performed. In the action of force-feeding—despite its great costs, and its obvious entrée into the realm of torture—the US demonstrates the great need it has to maintain the body in a perpetual state of political and medical limbo, in the realization of its own power.

Resistance, Imagination and Solidarity

“Not once did it occur to me to stop my hunger strike. Not once.”

– Ahmad Zuhair, Guantánamo Bay[53]

“Your freedom is our freedom and our freedom is your freedom!”

– Ameer Makhoul, Gilboa Prison, Israel[54]

By undertaking an indefinite hunger strike, despite the daily torture endured as a result, Guantánamo inmates risk the death of their bodies as a potential catalyst for freedom from psychic death. They demonstrate their recognition that death of the self is the purpose of the mechanisms of the prison—and that by denying it this possibility, by destroying the body, this power is wrested away and some small shred of humanity is reimagined and retained.

The hunger strikes, as so many prisoners have reminded us, are not about death, but about life—and not just any life, but the freedom to live the life one chooses. And a major purpose is to create support and solidarity, to bring to light the suffering that occurs in the shadows. In the Standard Operating Manual, the US military has also foreseen this problem. It states: “in the event of a mass hunger strike, isolating hunger striking patients from each other is vital to prevent them from achieving solidarity.”[55]

And that solidarity, though still less than what is necessary, has been significant. A quick search of the Internet yields statements from individuals, organizations, artists, musicians, and other political prisoners themselves expressing their support for the hunger strikers. In one incredible act of solidarity with Palestinian political prisoner Khader Adnan, whose conditions at the time were rapidly deteriorating, former Irish Republican Army hunger striker Tommy McKearney recorded a video in which he stated, “He is battling against atrocious conditions in a very unjust system…the world must intervene to save this man’s life in the name of humanity, in the name of decency, in the name of justice, and legality.” In Amman, Jordan filmmakers and activists edited and complied video of the 190 days of Adnan’s strike, with a different person holding a sign in support of him each day. The video is moving, all making clear the admiration and respect for Adnan’s struggle for liberation.[56]

These acts of solidarity haven’t remained simply between individuals inside prison and their loved ones outside, but horizontally between the prisoners themselves. In Bahrain, revolutionary activist Abdulhadi al-Khawaja was on hunger strike to protest his jailing for leading the pro-democracy uprising in Bahrain.[57] Palestinian political prisoner Ameer Makhoul issued a letter of solidarity to al-Khawaja from Gilboa Prison, saying:

“When the will is free and the cause is just, and you embody both, the human is capable of making miracles happen, and no oppressive, tyrannical, murderous regime can harm it, not the Bahraini regime, subject to US colonial imperialism, or the Israeli colonial system in Palestine. It is the system of colonialism and its puppet regimes that have lost all legitimacy, while the people are legitimacy and its source.”[58]

By looking at the correspondences between prisoners, there is much to be learned about how hunger-striking inmates view their struggles, the histories they are grounded in, and the shared visions that motivate and inspire them. In Makhoul’s statement, it is clear that their incarceration is understood as an extension of a colonial operation, and does not distinguish between those behind bars in Bahrain and in Israel. The hunger strikes are related, international and anti-colonial at their foundation. Makhoul includes in his letter to al-Khawaja a poem called “The Martyr:

I will carry my soul in my hand

And throw it in the valleys of death

It is either a life that makes a friend happy

Or a death that makes an enemy angry

The noble man’s soul has two goals

To die or to achieve its dreams

What is life if I don’t live

Feared and what I have is forbidden to others

When I speak, all the world listens

And my voice echoes among people

I see my death, but I rush to it

This is the death of men

And whoever desires an honorable death

Then this is it

How am I patient with the spiteful

And patient with all this pain?

Is it because of fear?

While life has no value to me!

Or humiliation? While I am contemptuous!

I will throw my heart at my enemies’ faces

And my heart is iron and fire!

I will protect my land with the edge of the sword

So my people will know that I am the man

Abdelrahim Mahmud, 1937[59]

This poem was written in 1937 by a man who left his literature studies at Bir Zeit University to join the fight against Zionist forces in Palestine. Ten years after writing this poem, he was killed on the battlefield. Nearly 70 years later, his words were revived by Makhoul, who proclaimed to al-Khawaja: “As you carry your soul in your open hunger strike, behind this is the essence of your position—that you love life; only he who loves life has the courage and the will to sacrifice for freedom and human dignity and the dignity of his people and the country’s freedom.”[60] In a sign-off reminiscent of the farewells of Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos,[61] Makhoul sends his greetings “From the fleeting Israeli prison of Gilboa prison, no matter how long the captivity.”[62]

Makhoul’s statement itself is a poignant expression of resistance, as dissolution of these connections is a central motivation of his jailers:

“In past years I have stood in solidarity with you from Haifa, from the captive nation of Palestine, which surrounds the racist, colonial, Zionist project; and today I am in solidarity with you while in an Israeli jail, two years out of an unjust nine-year sentence—a high price imposed by the colonial system on Palestinian leaders of 48 to deter them from communication with the Arab people throughout the Arab world, and the price of our interaction with people’s movements and struggles for their freedom and the freedom of Palestine and its people.”

In a political environment in which creative mechanisms of confinement have been established in order to isolate, break, punish, and neutralize individuals, hunger strikes have been a catalyst for international solidarities to flourish and for inmates to locate themselves within a larger genealogy, a larger community, and a larger struggle. This is one of the foremost reasons they have been met with such overt violence, anger, and fear from prison authorities.

Dreaming of the Day

“The most important political discovery of enslaved freedom is that of freedom” – E. P. Ziarek [63]

In his diary of a hunger strike, Loai Odeh says, “during these days there is no place for irritation.” The hunger strikes give a reason, something to commit to, to take control of, an incentive not to react to the attacks of the prison administrators and governments, to reserve energies, to refuse petty quarrels, to stand with each other, and to nourish determination. Under a hunger strike, these daily battles fall away in the face of a more sober, serious, and meaningful form of resistance. One may settle into determination, and walk the higher ground knowing that resistance is in his hands—and that despite counterattacks, one has a position and a power that he may, and must, hold onto. Each day, rather than imagining how he will withstand the suffering he faces, Odeh describes a scene in which individuals are, “dreaming about the day the hunger strike ends with victory.”[64]

This might be dismissed as idealistic, even dangerously optimistic. And yet, there is actually something deeply revolutionary about sustaining hope, literally, in the face of death—and the willingness to face death as a manifestation of that hope. With utmost relevance to the circumstances of Odeh, Hassan, and others, Kristian Williams speaks of the power of idealism in the face of a harrowing reality:

“While many have read such prisoners’ political formulations as thin polemics and/or nihilistic meanderings, there is in fact a profound idealism embedded in this cognitive praxis. That is, to refuse the legitimacy of one’s subjection, to shatter the coerced silence and invisibility of state terror’s final solution, is also to imagine the re-making of society in the face of state terror’s ultimate failure to totalize social intercourse.”[65]

This imagination is not one to be romanticized, nor is it appropriate to ignore the conditions from which it comes. It is not the imagination of a child playing peacefully in a family garden, but one of a prisoner who finds strength and hope in the midst of a sometimes overt, sometimes banal, but always torturous and indefinite reality in which he is reduced to a dehumanized entity. And while we cannot overwrite the variety of meanings behind the decision to refuse food, which undeniably involve motivations which range from release from captivity to death itself, it is clear that it is a decision borne out of a determination to shatter the chains that bind them.

There are a wide range of circumstances, identities and political backgrounds of hunger striking prisoners in the US. At an immigration detention center in Tacoma, Washington, inmates started a mass hunger strike on March 8, 2014. Though official records indicate that 150 people were still striking as of March 11th of that year, inmates inside have said that 1,200 inmates were participating.[66] More than 20 of them were placed in isolation as a result. Simultaneously, in Arizona, six immigrant detainees began a hunger strike to demand their release from Eloy Detention Center in March 2014. Eloy is a privately owned facility that houses male and female immigrants and is called a “deportation machine,” deporting over 1,000 people a day. Nor is this the first hunger strike at Eloy. In August 2013, official reports cited 70 inmates began one of the largest hunger strikes in the prison’s history.[67] In both cases, striking prisoners were joined by folks on the outside, refusing food in solidarity.[68] The list continues. Since 2011, the mainland US has seen mass hunger strikes in Georgia,[69] California’s notorious Pelican Bay Secure Housing Unit,[70] and then statewide in California,[71] Texas,[72] Maynard, and Illinois.[73] Grievances cited by inmates are the same from prison to prison, and are strikingly similar to complaints cited by inmates at Guantánamo and Israeli prisons.

If the prison in modern democratic nations is intended to create conditions of living death, and is intertwined with the discourse of human rights and justice; and if the state relies upon the invisibility of its violence; then the hunger strike contains within it the seeds of radical transformation. In grounding hunger strikes in a political context, in which it is not which politics are being defended but rather the right to live freely and according to a politics of one’s choosing, it becomes clear how it is that we have seen individuals from diverse political, ideological and geographic backgrounds sharing common forms of resistance in order to challenge their detention. It is the willingness—and the determination—to risk self-destruction to convey a message of political resistance which demonstrates the conditions for the possibility of turning confinement back upon itself by taking control over, ironically, the one thing the state has attempted to reduced them to—the body. The hunger strike is a logical manifestation of the wars waged over life and death behind bars and exposes the truth that the greatest political discovery of unfreedom is that of freedom and that the greatest possibility of repression is that of imagination and rebellion.

Brooke Reynolds is an organizer with the Jericho Movement for political prisoners in the US, a musician, and an herbal medicine maker. She works to draw connections between COINTELPRO-era political imprisonment and post-War on Terror uses of incarceration, to highlight the uses of prisons as tools of warfare in the US, and to bring healing and support to those who have been disappeared behind bars. She holds an MA from New York University in Near Eastern Studies.

NOTES:

[1] David Remes, “The Tragic Death of Adnan Latif: What Is the Government Trying to Hide?” Truthout, December 17, 2012.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Luis Ramirez, “Guantánamo Prison Hunger Strike Grows,” VOA, May 8, 2013, accessed May, 2013.

[4] Samir Naji Al Hasan Moqbel, “Op-Ed Contributor: Gitmo Is Killing Me,” The New York Times, April 15, 2013, accessed May 6, 2013.

[5] Shahd Abusalama, “’The First Day Is the Hardest’: Ex-prisoner Loai Odeh’s Hunger Strike Diary,” The Electronic Intifada, April 25, 2012, accessed April 1, 2014.

[6] Miriam Abu Ali, sister of Ahmad Abu Ali (who is being held at ADX Florence in Colorado as this is written), noted this pain in stating: “It’s not like a death: you don’t grieve and then finish, because this is not the past. In fact, it’s not even in the back of my mind—it is always there—this is chronic, after nine years, and it’s not going to end.”

[7] Moazzam Begg and Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantánamo, Bagram, and Kandahar (New York: New, 2006), 53.

[8] E. P. Ziarek, “Bare Life on Strike: Notes on the Biopolitics of Race and Gender,” South Atlantic Quarterly 107.1 (2008) 89-105.

[9] Laleh Khalili, Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2012).

[10] Giorgio Agamben, and Daniel Heller-Roazen. Homo Sacer (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1998).

[11] E. P. Ziarek, “Bare Life on Strike: Notes on the Biopolitics of Race and Gender,” South Atlantic Quarterly 107.1 (2008) 89-105.

[12] Shahla Talebi and Sūdābah Ardavān, Ghosts of Revolution: Rekindled Memories of Imprisonment in Iran (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2011). (Former Iranian political prisoner Shahla Talebi and the inmates she was held with in Iran had titled their prison camp—complete with mechanisms of torture, abuse, isolation, and death—the dastagh, or “human-making machine.”)

[13] A. Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15.1 (2003) 11-40.

[14] Laleh Khalili, Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2012), 74.

[15] The Treaty of 1934 between the United States and Cuba allowed the US to maintain sovereignty in Guantánamo Bay despite not owning it.

[16] Laleh Khalili, Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2012).

[17] Lexi Finnegan, “Cleared for Release but Denied Freedom–Shaker Aamer and Guantánamo Bay,” Huffington Post, April 26, 2013, accessed May 12, 2013.

[18] No women were ever held at Guantánamo Bay.

[19] Lexi Finnegan, “Cleared for Release but Denied Freedom–Shaker Aamer and Guantánamo Bay,” Huffington Post, April 26, 2013, accessed May 12, 2013.

[20] Victoria Brittain, John Berger, and Marina Warner, Shadow Lives: The Forgotten Women of the War on Terror (London: Pluto, 2013).

[21] Moazzam Begg and Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantánamo, Bagram, and Kandahar (New York: New, 2006), 326.

[22] Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret Wars against Domestic Dissent (Boston, MA: South End, 1990).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Sohail Daulatzai, Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom beyond America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2012).

[26] “Communications Management Units: The Federal Prison System’s Experiment in Social Isolation,” (Issue brief, New York, Center for Constitutional Rights, 2012).

[27] Jeanne Theoharis, “Guantánamo in New York City,” The Nation, September 25, 2013, accessed February 27, 2014.

[28] Pardiss Kebrieaei, “The Torture That Flourishes From Gitmo to an American Supermax,” The Nation, January 30, 2014, accessed February 27, 2014.

[29]Ibid.

[30] Banu Bargu, “Forging Life into a Weapon,” Social Text, May 21, 2011, accessed April 9, 2014.

[31] E. P. Ziarek, “Bare Life on Strike: Notes on the Biopolitics of Race and Gender,” South Atlantic Quarterly 107.1 (2008) 89-105.

[33] “11 Palestinian Prisoners on Hunger Strike Protesting Prison Abuses.” Samidoun Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network, accessed March 21, 2014.

[34] These men are Anees Doula (1980), Ali Al-Ja’fari (1980), Rasim Halawa (1980) and Issehak Maraghah (1983). Gavan Kelley, “Palestinian Prisoner Hunger Strikes,” Online interview, March 18, 2014.

[35] Over 100 Palestinian prisoners did in fact begin a hunger strike in Israeli jails on April 24, 2014.

“Over 100 Palestinian Prisoners Begin Hunger Strike to Protest Israeli Administrative Detention,” Mondoweiss, April 27, 2014, accessed May 1, 2014.

[36] Adam Horowitz, “Israeli Docs to Consult US Govt on Force Feeding Gitmo Hunger Strikers,” Mondoweiss, July 9, 2013, accessed March 26, 2014.

[37] Gavan Kelley, “Palestinian Prisoner Hunger Strikes,” Online interview, March 18, 2014.

[38] Andy Worthington, “The Guantánamo Experiment: A Harrowing Letter By Yemeni Prisoner Emad Hassan,” Eurasia Review, February 20, 2014, accessed March 26, 2014.

[39] World Medical Association, “WMA Declaration of Malta,” (Declaration, Malta, St. Julians, 1991).

[40] George J. Annas, J.D., M.P.H., Sondra S. Crosby, MD, and Leonard H. Glantz, J.D, “Guantánamo Bay: A Medical Ethics-free Zone?” The New England Journal of Medicine 369.2 (2013) 101-03.

[41] George J. Annas, J.D., M.P.H., Sondra S. Crosby, MD, and Leonard H. Glantz, J.D, “Guantánamo Bay: A Medical Ethics-free Zone?” The New England Journal of Medicine 369.2 (2013) 102.

[42] For example, Guantánamo Bay was occupied by the US in 1898 and retained a perpetual lease from Cuba in 1903 that it continues to operate under today, despite protestations from the Cuban government and people. See Rebecca Tsosie, “Indigenous Peoples and Epistemic Injustice: Science, Ethics, and Human Rights,” 87(4) Washington Law Review 1133 (2012); Robert A. Williams Jr., The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourses of Conquest (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

[43] Jeanne Theoharis, “Guantánamo in New York City,” The Nation, September 25, 2013, accessed February 27, 2014.

[44] United States of America, Joint Task Force: Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, “Standard Operating Procedure for the Medical Management of Detainees on Hunger Strike (2013), 2.

[45] Ibid., 1.

[46] Lila Rajiva, The Language of Empire: Abu Ghraib and the American Media, (New York, NY: Monthly Review, 2005).

[47] United States of America, Joint Task Force: Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, “Standard Operating Procedure for the Medical Management of Detainees on Hunger Strike (2013), 2.

[48] Moazzam Begg and Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantánamo, Bagram, and Kandahar (New York: New, 2006), 165.

[49] These include Pulmocare, Mylanta, Tylenol, Benadryl, Motrin, and Phenergan.

[50] “Safety Restraint Chair,” Safety Restraint Chair, E.R.C Inc., accessed May 1, 2014.

[51] Tim Golden, “Tough U.S. Steps In Hunger Strike At Camp In Cuba,” The New York Times. February 8, 2006, accessed March 29, 2014.

[52] United States of America, Joint Task Force: Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, “Standard Operating Procedure for the Medical Management of Detainees on Hunger Strike (2013), 19. Emphasis mine.

[53] Ben Fox, “Ex-Guantánamo Detainee: Forced-feeding Was Hell,” Ex-Guantánamo Detainee: Forced-feeding Was Hell, June 15, 2013, accessed April 2, 2014.

[54] Ameer Makhoul, “Letter of Solidarity from Palestinian Prisoners to the People of Bahrain,” Witness Bahrain RSS, April 18, 2012, accessed March 25, 2014.

[55] United States of America, Joint Task Force: Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, “Standard Operating Procedure for the Medical Management of Detainees on Hunger Strike (2013), 11.

[56] Ali Abunima, “VIDEO: Former Irish Hunger Striker’s Message for Khader Adnan, a Palestinian Prisoner 55 Days on Hunger Strike,” The Electronic Intifada, September 2, 2012, accessed March 25, 2014.

[57] Maureen Clare Murphy, “Mass Hunger Strike Grows despite Israel’s Best Efforts to Repress It,” The Electronic Intifada, April 25, 2012, accessed March 24, 2014.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Abdelrahim Mahmoud, “The Martyr,” Mediamonitors.net, accessed March 25, 2014 (English translation); Abdelrahim Mahmoud, “Al-Shaheed,” Adab.com, accessed March 25, 2014, (Arabic original).

[60] Ameer Makhoul, “Letter of Solidarity from Palestinian Prisoners to the People of Bahrain,” Witness Bahrain RSS, April 18, 2012, accessed March 25, 2014. (This statement is available as an English translation. According to the research efforts of the author, the site where the original Arabic was posted has since been taken down.)

[61] In his Conversations with Durito, such farewells are common. Here is an example: “Vale. Salud, and a mouthful of this fresh air that, they say, is breathed in the mountains and that some displaced people call ‘hope.’ From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast, Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos”

[62] “Of Sowing and Harvests: Subcomandante Marcos on Gaza,” My Word is My Weapon, January 6, 2009.

[63] E. P. Ziarek, “Bare Life on Strike: Notes on the Biopolitics of Race and Gender” South Atlantic Quarterly 107.1 (2008) 89-105.

[64] Shahd Abusalama, “’The First Day Is the Hardest’: Ex-prisoner Loai Odeh’s Hunger Strike Diary,” The Electronic Intifada, April 25, 2012, accessed April 1, 2014.

[65] Kristian Williams, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, (Cambridge, MA: South End, 2006), 198.

[66] “Detainees At Northwest Detention Center on Hunger Strike Demanding Improved Living Conditions, Health Care,” Not1More Deportation, accessed March 21, 2014.

[67] Aura Bogado, “A Girl Hanged Herself Here,” Colorlines, August 1, 2013, accessed March 21, 2014.

[68] Aura Bogado, “Attacks, Arrests and Deportation for Immigrant Hunger Strikers,” Colorlines, February 26, 2014, accessed March 21, 2014.

[69] “On Strike Since June 10th,”Georgiahungerstrike.wordpress.com., accessed March 21, 2014.

[70] “Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity,” Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity, accessed March 21, 2014.

[71] Dan Berger, “What’s Behind the Hunger Strike at Northwest Detention Center,” The Seattle Times, March 19, 2014, accessed March 21, 2014.

[72] “Hunger-Striking Immigrants in Private Prison Report Retaliations,” Democracy Now! March 21, 2014. This strike is taking place in a privately run immigrant detention center, which is owned by the same company as Eloy detention center, the for-profit GEO group.

[73] James Anderson, “Hunger Strike at Menard Correctional Center Draws Solidarity, Support,” Truthout, February 7, 2014. Fifteen men have been on hunger strike since January 15, 2014 to protest administrative segregation and conditions.