Fleshing

The teacher hands me a deer hide from a 50-gallon drum. My arm strains as I hold its heavy, slimy, dripping weight out in front of me, high so that it won’t drag in the dirt. I carry it to my fleshing beam, a wide PVC pipe cut in half, the end cut into a half circle. The hide drapes over it fur side down, and I begin the process of fleshing—using a long, thick, dull metal blade with handles on both ends, to scrape away any remaining bits of meat and fat from the hide, hands on either end of the scraper, working it downwards. Bits of flesh falling to the dirt. Surrounded by the musky scent of the deer in the afternoon heat.

I’m mid-way through a meandering road trip home to Oregon, pausing in the occupied lands of the Tohono O’odham for a hide tanning class, after leaving my job in the Deep South. Camping among a group of people gathered in the desert to learn and teach traditional skills, this was the first moment of community and safety that I’ve had in months. My winter had been spent in isolation, with a constant, dull pulse of fear. I’d found myself in this class in the Sonoran Desert by following the thread of what has always made me feel safe and connected. A thread that stretches from the past to the future.

It had been my fourth winter working for Ted, a billionaire many times over, who’d hired me as his private chef. I fed him and his friends seven days a week as they hunted ducks at his vacation lodge deep in the Delta.

I had my interview in an airport. His manager, Randy, had flown in to meet me. Through a miscommunication he’d flown to an airport in the wrong city that morning, and had rescheduled for the afternoon, after he booked another last second flight. We talked through logistics, both of us already knowing that I’d be taking the job. I blanched when he asked if I was single. A crack in the veneer of his professionalism. I noted to myself to be careful of him.

The first night that I worked for Ted, at his massive Montana ranch, I listened in on his dinner conversation. He told stories of hunting trips with Justice Scalia, and Dick Cheney. “Such a nice guy, but kinda scary when he starts talking politics!” It was the first of what would become many times that I heard the story of the night his buddy Kip played “Sweet Home Alabama” on the guitar at their country club, with Condoleeza Rice on keys, and a full set of back-up singers who worked at the club.

By the 1500s, across Western Europe, something we now call the Enclosure of the Commons was beginning. Shared land for gathering firewood and food, and hunting, was privatized, taken over by the European aristocracy. Leaving a poor, landless mass of people. With their ancient right to live off the land stripped away their labor was all that was left to support them.

In the first phase of capitalist development, women were at the forefront of the struggle against land enclosures both in England and in the “New World” and they were the staunchest defenders of the communal cultures that European colonization attempted to destroy.

– Silvia Federici, Feminism and the Politics of the Commons

In her book Caliban and the Witch Silvia Federici describes the various class warfare tactics enacted against the working class, specifically the women, by the aristocracy of Europe during the development of capitalism. She describes the wildfire spread of witch burnings as a political tactic by the ruling class to diminish the power of working-class women, who had been at the forefront of organizing protests against poverty, scarcity, and unjust working and living conditions. Witch trials seeded distrust among the working class and fractured and further traumatized families and communities. Families and communities were marked with unnamable loss and the smell of smoke. Having perfected the project of colonization on its own people, the European aristocracy sent the starving, traumatized, and landless people to the Americas and beyond to reenact what had been done to them on the Indigenous peoples of those lands.

Graining

With the fleshing complete, I flip my hide over. Using the same long dull blade, I begin scraping away the fur, layers of epidermis, and grain. If left on, the grain hardens and becomes stiff, giving you a hide that’s more like stiff tarping than soft and pliable buckskin. Bending at the waist over the propped-up PVC pipe, I use the full strength my arms and back, stroke after stroke, to peel away the layers. Leaving only what will remain soft.

This winter, as soon as I pulled into the Delta, my coworker Tammy texted me: “Shit’s crazy this season. Be careful who you talk to.”

My first day back in the lodge, Tammy, the housekeeper Caroline, and I pretended to work, aware of the surveillance cameras on us, as they told me stories about Randy being sexually inappropriate with current and past female employees. I had been struggling with him delaying my payments and enrollment in health insurance over the past year, after I’d told him that I wasn’t flirting with him. It’s a boring story not worth telling. My issues with him had felt manageable. I’d dealt with worse, but hearing the greater pattern of his behavior of him pinning a woman against the counter, groping her, asking her to go to the bedroom with him, and firing her after she refused him. I no longer felt able to be complicit.

I initiated an HR investigation against him. Tides of fear came crashing in, the stored fear from the generations of women in my family who knew the consequences of standing up to power. Leaving me with bouts of vertigo. I smelled ancient smoke. I made a small altar in my apartment for my ancestors, the women who came before me. I would place small dishes of food on it and buy fresh flowers for it once a week when I’d make my hour and a half drive to the grocery store.

I spent my off hours wandering the delta contained in Ted’s 20,000-acre property, maintained to be perfect duck habitat so that he and his friends could proudly shoot their limit each morning. He delighted in stories of his hunting guides playing vigilante and chasing out local hunters who were trespassing, and who would be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

I’d walk the flooded timber in my muck boots, with a basket and knife. Sometimes wading through waters that were too deep for my boots, allowing them to fill with water, marveling at the abundance of mushrooms-turkey tail, wood ear, and witches butter, gathering lion’s mane and oyster mushrooms with their light licorice scent. I filled my basket with fallen acorns and spent Christmas alone in my apartment, shelling them, and leaching them of their tannins to make flour. This was my refuge.

If it is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it’s useful, edible or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people, and then later on you take it out and eat it or share it or store it up for winter in a solider container or put it in the medicine bundle or the shrine or the museum, the holy place, the area that contains what is sacred, and then next day you probably do much the same again – if to do that is human, if that’s what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully freely gladly, for the first time.

– Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction

I lived in a state of vigilance, acutely aware of the possibility of retaliation, and of my vulnerability living on the isolated property where I worked. No locks on my doors or cell service. In an apartment above the manager’s office, and no one that I could trust for thousands of miles. It was a season of paranoia that worked out the way that these things do.

Randy was protected. I left at the end of the season after working with Ted, in his homes, for years. The culminating experience of a life in the service industry and the catalyst for me to leave it. I’d unintentionally continued on the path that had been modeled to me.

Braining

With the hide thoroughly scraped, I put it in a bucket of solution made of brains and water, letting the internal fiber structure of the hides become fully saturated. Humans discovered, thousands of years ago, that the brain of an animal can be used to tan its hide to create buckskin. The naturally occurring fats found in brains condition the fibers of the hide.

Brain tan was the everyday garb of the American Indians when the Europeans first arrived, but in Europe the availability of deerskins to the commoner had long since disappeared. Only the aristocracy were allowed to hunt.

– Matt Richards, Deerskins into Buckskins

My dad, raised by a single mom, began working as a child to help support his family. He moved out at fifteen to live and work on a ranch, tending cattle and hay fields. Determined to rise from his working-poor origins, he crafted a career out of catering to, and emulating in the ways that he could, rich men. He began a fly-fishing guide service. For his clients, he represented the dream of freedom and connection to passion and wildness. For him, they represented a different kind of freedom—financial—and the respect of status and accomplishment.

My sister and I began working for him on the river when I was eight and she was ten. My dad taught me to make gin and tonics, and the perfect mojitos. In the evenings in camp I’d fix their drinks. They loved the novelty of a little girl bartender. I’d listen to these men, many of whom were polite, some of whom were not, share their banal jokes and stories. Two of our regulars, brothers who owned a ski resort, described their sex trips to Thailand, and watching women shoot ping pong balls out of their pussies, with my sister and I sitting a few feet away.

As I got older, I realized that I represented a different kind of fantasy than my dad. Men who had granddaughters older than me would spend their trip joking about what a perfect wife I would be to them. They’d offer me a glass of scotch. Make a dirty joke. Watch me to see how I would react. Ask my male coworkers if I would be doing a table dance for them after dinner. They’d thank me at the end of the trip for cooking for them, although it’d been my male coworkers who’d done that, and they’d seen me carrying their heavy bags on my back up and down the beach.

I learned quickly how to take care of myself. Early on, I formed an incisive and cutting sense of humor, that with a smile, could deflect inappropriate jokes and comments. Humor was my main line of defense, a subtle boundary that wouldn’t upset these men that we depended on for our livelihood. My dad needed them to come back every year, and to keep them happy so they’d tip him a stack of bills at the end of the trip. From my dad I learned to create a caricature of myself, a mask of civility and accommodation, with a few threads of authenticity woven through for interest. I learned to anticipate and take care of their needs before them to avoid interaction. I shielded my wildness from them. I was good at my job.

Softening

Once fully saturated, the hide is draped over a strong line or the top rail of a gate, or something similarly sturdy and folded into a donut shape. Using a bar or stick through the center, holding each end, I use the weight of my body to twist the hide taut, allowing the tanning liquid to drain off. This is repeated, several times, rotating directions, until all the excess moisture has been pushed out. Then I began the process of softening, which can be done many ways. I use a metal cable that is secured to something vertical like a tree, at the top and bottom. The hide is looped through the cable, holding onto each end of the hide I forcefully work the hide back and forth, rubbing it on the cable. With hands and arms that are tired from graining, I rotate the hide and work the whole thing. Once you begin softening, you have to work the hide continuously until it’s completely dry to get a soft, pliable buckskin and to avoid hard crunchy spots. You’re ensuring that the woven internal structure remains open.

If we could look back far enough, nearly every one of us would find some ancestor who lived their lives wearing this wonderful garment. It’s something we have in common. Getting skins soft was undoubtedly one of the very first arts that ancient humans developed.

– Matt Richards, Deerskins into Buckskins

In the off-season, and in the summers before I began working, I lived in what was essentially a matriarchy. My dad would be gone for months at a time, guiding clients on international trips, leaving my mom, sister, and me alone. Although my parents were married, my mom operated as a single parent for most of the year, while my dad was away and unreachable taking clients on lavish adventures to Fiji, Mexico, Cuba, or Patagonia. We lived in the same small town that my mom had grown up in, three of her sisters—all single mothers—lived nearby. Having lost both parents as children and spouses at young ages, they stuck together. They put themselves through school and worked as they raised us. There was a fluidity of resources between households. At times, households would merge when one of my aunts was having a hard time. Holidays and birthdays were spent all together, at our house or one of my aunts’, with dinners or outings together in between.

They’d sit around and blithely tell their stories over plates of baked potatoes. Aunt Siobhan would sit on the heart of fireplace, blowing her cigarette smoke up the chimney. They’d laugh recalling when my mom and Siobhan, both eight months pregnant with their first children, stood on the curb of the emergency room. People passing by them staring and glaring, as the two of them chain-smoked cigarettes, although they’d both quit for their pregnancies, as they waited to hear if Siobhan’s husband, who’d fallen in a roofing accident, could be taken off life support. The settlement money after his death provided her more financial stability than the rest of us, until her son turned eighteen.

I took these stories on as my own, carrying them on my small shoulders, carrying guilt for having an easy life.

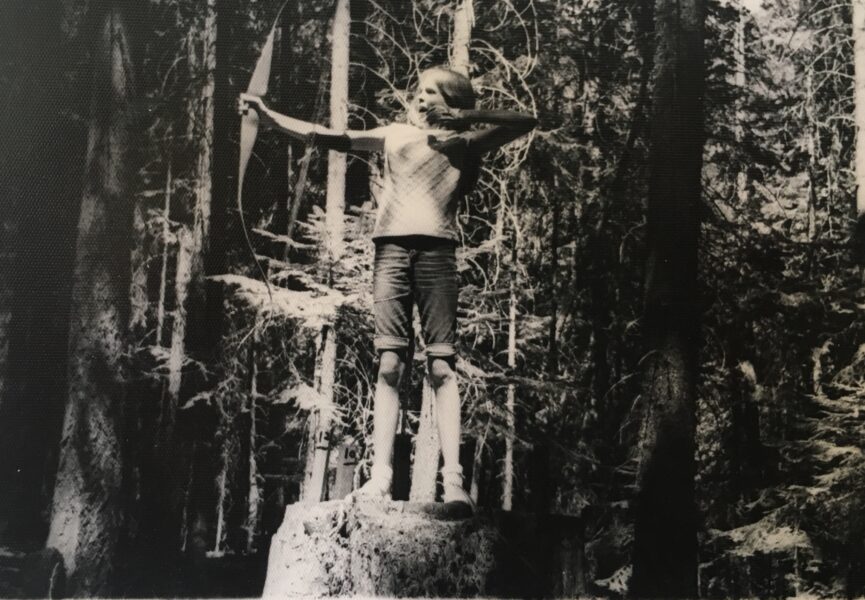

When I was eight, my mom surprised my sister, cousins, and me by picking us up at school with the car loaded with camping equipment. We headed to the mountains where she set up empty soda cans on stumps to teach us to shoot the .22 pistol that her dad, who’d been an avid hunter, had given her before he’d died, when she was eight.

In the spring we’d go up to the mountain near our house to gather morel mushrooms. Wandering the forest, eyes on the ground, scanning for their little brown humped backs popping up from the forest floor perfectly matching the fallen pinecones.

In the summers we’d go to the mountain, where my mom and her sisters’ parents had taken them, to picnic: hard rolls, cheese, salami, and mayo from Safeway, and pick huckleberries to freeze for the winters. My aunts would spread across the hillside sitting cross-legged among the bushes, filling their Safeway bags with berries. My cousins and I would dig holes in the forest floor, covering them with pine boughs, dreaming of the animals we’d trap, never successfully.

In the winter we’d take a bag of huckleberries from the freezer and eat them frozen like cereal, in a bowl with milk and a heap of sugar, the milk tie-dyed purple. Transporting us back to the summer and the way the berries tasted warmed in the sun, and the resinous cinnamon smell of ceanothus bushes and pines.

Smoking

With the hide fully dry, I stitch shut all the holes, then fold it in half lengthwise, using thread or staples to secure the edges together, leaving a hole in the bottom. I attach a portion of a denim pant leg to that hole, essentially creating a pillowcase with a tube coming out of the bottom. With a fire going in the fire box, fed by punk wood (rotten wood that’s used to keep the fire smoldering and not too hot), I suspend the hide by tying it to tree branches above the fire box. I pull the bottom of the pant leg over the top of the short length of stove pipe, allowing the hide to fill with smoke. It’ll eventually be turned inside out and reattached so both sides can be smoked. Through the smoking process, the work that’s been done up until this point is fixed. The formaldehyde and other preservatives in the smoke soak into the fiber structure, ensuring that if the hide becomes wet it won’t shrink up again and become rawhide. The smoke transforms the bone-white buckskin shades of golden honey.

Through this process of alchemy, time, smoke, and the intimacy of work, death is transformed into something new, soft, and lasting. Forever carrying the smell of smoke.

Mattie Ecklund is former personal chef. She attended the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, OR. She is currently working on a chicken farm gutting chickens, and at a hotel cleaning rooms, while preparing to go to grad school. She lives in the mountains of Northeast Oregon where she gardens, forages, and creates recipes incorporating herbal medicines and wild foods. She can be found on Instagram @horizonlinesss

(all photos from the author)