Introduction

In her book Staying with the Trouble (1), wise earthling and “multispecies feminist theorist” Donna Haraway counsels us that the key to collectively surviving our catastrophic times is to look neither to a distant future—whether “apocalyptic or salvific”—or to a mythologized past. Rather, it is to stay here, conscious and creative, deeply enmeshed in a present thick with mortal lives and messy meanings, remaining symbiotically intertwined, in murky embrace, with all the other chthonic beings—the tentacular critters of earth. She calls this the “Chthulucene.” With these relatives, she suggests, instead of seeking transcendence, we might seek continuous ongoingness, in places damaged by an age of capitalism, colonialism, plantation-system agriculture, and carbon-extractive industry.

Suggesting possible pathways through and beyond planetary devastation—that is, from Anthropocene (or Capitalocene) to Chthulucene—Haraway guides us through the entangled threads of some examples of present-day “sympoiesis” (making together). These are scenarios in which “the sustaining creativity of people who care and act animates the action,”(2) wherein the boundaries dividing human/animal, art/science/action, and body/biology/technology/ecosystem begin to erode. She urges us to study and practice “humusities”, not humanities, and to weave kinship among all the “Children of Compost,” as she names the more-than-human terrestrial community of “The Camille Stories,” a collaborative work of speculative figuration exploring a beautifully revitalized possible alternative future (of symbiosis with migratory butterflies).

Camille, meet Kevin Doyle. His alternate account of a campaign to save a windswept Irish peninsula from development as a luxury golf course, defending access to the terrain for all locals, strikes me as eminently Chthulucene.

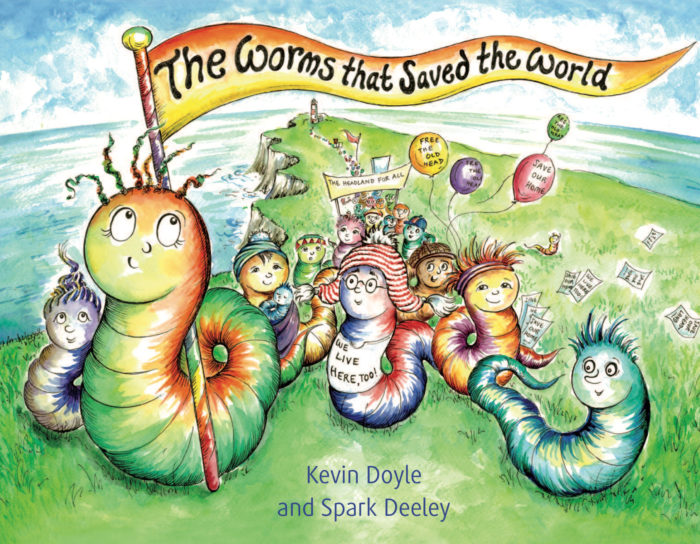

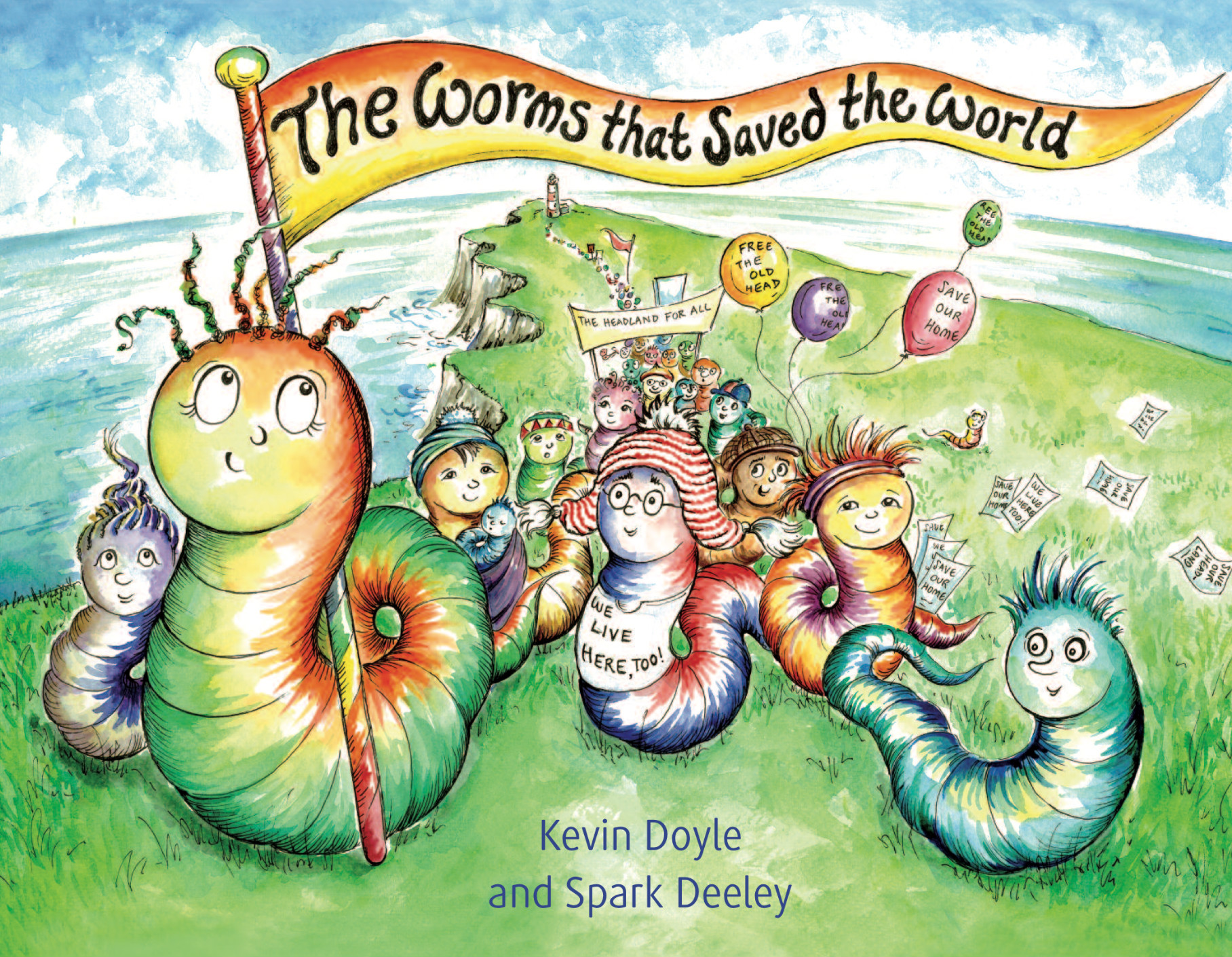

Starting in 2001, organizers challenged this new enclosure through an escalation of creative direct actions on the land. Though the protests were defeated, Doyle and artist Spark Deeley turned the setback into a teachable moment for activating reflection and reimagination, a pragmatic stepping stone to enable hope and future struggle. That is, they created a book for kids. In The Worms that Saved the World, a community of feisty invertebrates, realizing they can’t save their threatened coastal home in isolation, join forces with the other birds and beasts with whom they share it.

Similar to Doyle and Deeley, Haraway observes that “[o]ne way to live and die well as mortal critters in the Chthulucene is to join forces to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust … recuperation and recomposition, which must include mourning irreversible losses”; of which there have been many and will be more.(3) She also reminds us that “[a]ctual places … are worlds worth fighting for; and each has nourished brave, smart, generative coalitions of artists/scientists/activists across dangerous historical divisions.”(4) And finally, “[t]he Children of Compost insist”—and who better to represent Children of Compost than heroic worms?—“that we need to write stories and live lives for flourishing and for abundance, especially in the teeth of rampaging destruction and impoverization.” Such a story can be “a pilot project, a model, a work and play object, for composing collective projects, not just in the imagination but also in actual story writing. And on and under the ground.”(5)

—Maia Ramnath, Perspectives’ Collective

- Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chtulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Haraway, p. 5.

- Haraway, p 101.

- Haraway, p. 98

- Haraway, p. 136

Q: Where is a good place to begin? A children’s storybook emerging out of a campaign that ended in defeat? How? Why?

A: A few reasons. First off, like so many campaigns and struggles that we are involved in, we lost but we shouldn’t have. What I mean is that justice was not done. Rather, we lost because the other side had deep pockets and they also had the police and the state on their side. They didn’t win because they were right or because that position had more validity than ours. Our campaign was a classic example of might winning out over right. So, I suppose, our book is a way of saying, “We’re not done here, actually.”

Q: Perhaps you could tell us something about the campaign that inspired the book?

A: Sure. It was a campaign that happened here in Ireland at a location called the Old Head of Kinsale. It’s a beautiful promontory of land with walking trails, bird sanctuaries and magnificent views of the ocean and the surrounding coastline. It has been a traditional walking destination going back through the generations. For generations the land there was farmland with these wonderful walks around and at the edges of it.

Then in the late eighties, the entire headland was purchased by a millionaire developer who had this dream of building a luxury golf course there. He wanted it to be exclusive, too, just for those who had a lot of money. He was aiming at the top end of the golfing business—where luxury intersects with exclusivity and unparalleled scenic position.

A campaign got underway. Many people wanted to preserve the headland as a public amenity, and these developers wanted to effectively privatize it. Our campaign—called Free the Old Head—emerged to take on the developers.

Q: How did the campaign develop and evolve?

A: In truth it was always going to be an uphill battle to win against a determined group of developers. We were up against people with lots of resources. Essentially the campaign took the shape of a series of mass trespasses whereby people went to where the golf course was and insisted on their right to walk onto the Old Head of Kinsale. It was direct action, and, at first, it was very difficult for the developers to stop the protests because they were large and defiant.

Eventually the developers went to the Irish courts, took on the Cork County Council and Ireland’s Planning Board, both of which opposed the restrictions on the public’s right to walk in the area. In the courts the developers made many outrageous claims and tried to suggest that “the entire right to private property in Ireland was in dispute.” Mad stuff. But the courts, well, they sided with the developers. Surprise, surprise, right?

As soon as they did, the Irish police—the Gardaí—rowed in to enforce the rule of law. It was touch and go after that. We really needed more public support and it didn’t arrive. So, in the end, public access was lost.

Normally defeat spreads dejection, and in our case there’s no doubt that was the case too. But it was really a highly spirited campaign, despite losing. A lot of people mobilized. There were some really big protests. People scaled walls and climbed big wire fences. There was a strong element of direct action mixed in with what were called “People’s Picnics,” which were very family friendly.

Q: Why a children’s book? Why that angle?

A: A few reasons, really. I suppose from the purely practical point, there’s a lot of creative space within fiction writing. Even more so in children’s fiction. It struck us that the fight at the Old Head of Kinsale was in some ways a metaphor for our times. It was a conflict involving the public good up against private greed. On this occasion privilege and greed won out, but we have to remember, too, that this cannot continue to be the case. We must start to win. The “public good” must begin to win out against privilege and greed. We cannot keep losing all these battles. So subconsciously there was a feeling, for me anyway, that I should write about it and imagine the alternative.

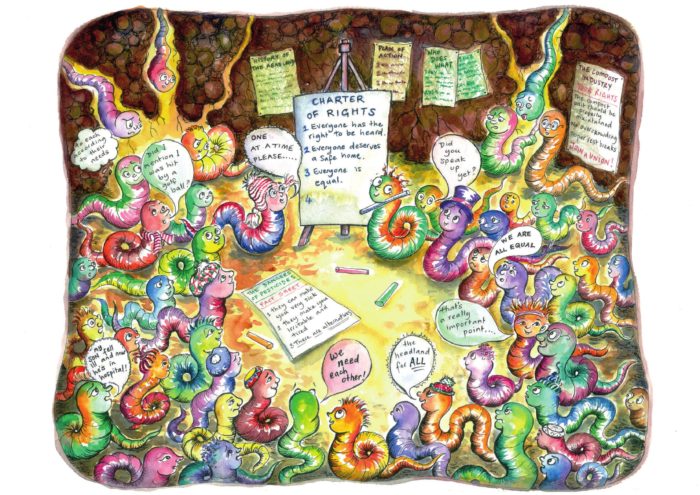

What happened at the Old Head of Kinsale, moreover, seemed to be perfect material to bring back to life in an imaginary way. So in our book, the story is carried forth by a community of earthworms. They live on an imaginary headland—on Ireland’s Atlantic coastline!—that is invaded by a luxury golf course development. Pesticides and insecticides are used on the land, and soon the worms are getting sick. However, they are rebels, and they speak up. They ask for consideration. The result is that the developers try to eradicate them. The earthworms make a valiant escape, but they know they have little hope on their own. A seagull—normally one of their predators—helps them, and this is how they make their grand breakthrough. They realize that they need to get help, so they set off to tell their story. They build a movement. … We won’t tell you the end, but they do win!

The book is aimed at children, but adults really get it, too. It’s nice to imagine winning. Another reason why a children’s book seemed ideal was that children don’t like injustice. When you talk to children about saving the planet from greed, you really are pushing an open door. And we want to tell a story that is optimistic about the possibilities ahead—even though they can sometimes appear bleak.

I guess, when we tell stories or sing songs about injustice and fighting back, we are in part administering therapy and in part defying the impact of defeat. Stories and songs are resistance and therapy.

Q: But the book is primarily aimed at kids?

A: Yes. Most definitely. It is an illustrated book in the best sense of that word. The artist who created the illustrations, Spark Deeley, did a wonderful job. The illustrations have a lot in them, and within some there are more stories—like the one where the worms have a mass meeting.

Also, the story is dramatic. The worms have to fight to survive. It’s an adventure and they make it through in the end. So it’s an adventure book, too. It is fair to say, though, that it is an “alternative” adventure book. I suppose it fills a gap in the book market. That was another side to why we chose to do a kid’s book.

Many activists are parents or will be parents or child-minders at some point in their lives. While the campaign to Free the Old Head was ongoing, I had young daughters myself. I’d be the first to say that there are some really great books out there, but there is a dire lack of books like ours about subjects like this.

Q: You mentioned a few reasons?

A: So many story books reinforce and uphold traditional values. This has been exposed in recent times around gender roles in particular. The video “The Ugly Truth about Children’s Books” is a great example. It’s on YouTube and well worth a look. A mum and her daughter remove books from a bookcase using the following criteria: Is there a female character? Does she speak? Do they have aspirations or are they just waiting for a prince? In the end there’s not a lot of books left for the mum and daughter to read. One bald fact tells you a lot: 25 percent of five thousand books studied had no female characters at all. For a range of children’s media, less than 20 percent of products showed women with a job, compared to more than 80 percent with respect to male characters. So around gender roles, we can clearly see biases in operation. Do these biases help in perpetuating a whole range of disparities that women and girls suffer in society? Of course they do. Conservative socialization is all around us and is dominant in so many spheres of life.

Moving away from gender temporarily, why would we be surprised if there were similar biases around topics like poverty, exploitation or challenging authorities? Of course there are. So in another way, in responding to what happened in our campaign in Cork, we are also addressing other issues not actually disconnected from our general struggle against injustice. People are passive and accept injustice often because they are socialized from a young age to be that way. We need to broaden the scope of radical ideas and alternatives. The area of young children’s fiction seemed an obvious place, in a way—and also an important place. Children matter, and they listen and question. We want to link up with that, I suppose.

We’ve described our book as “direct action for kids,” and that’s what we think our young citizens should know more about: in life, to be effective, direct action works.

Q: In the promo piece, you say, “a book for adults too,” right? Can you talk about this?

A: Adults can clearly see the simplicity of the story. It is a bit of a good-versus-bad tale, and none of the dreadful complications of adult life are really there. But adults like the idea of passing on their values to children, and this book offers opportunities for doing that.

Questions arise from any good story. So in our book, community and solidarity become central issues of survival. The importance of standing by people if they are picked on by more powerful people, by bullies if you like, is also part of the story. Children, sadly, are quite familiar with bullies, so this book is able to speak to them about this issue too.

A key anarchist idea is in our story, by the way; in fact, the plot turns on it. This is the idea of mutual aid. Species on our planet coexist, and there is cooperation, but do we hear much about that? Children hear lots about competition and the Darwinian idea of the survival of the fittest. So again there is room in the story to look at the idea of cooperation and how humans must in the end cooperate and respect the value of the environment.

So there’s room in the book for adults to talk and explain to children about different issues that arise. Or you can just read it for the adventure and fun of it.

Q: A lot of positivity from defeat, then?

A: Sure. The book is an imaginary celebration of fighting the good fight for justice. In our story—as you can see from the book’s cover image—the earthworms are happy rebels. The cover image, by the way, is from a point in the story before the worms have claimed outright victory. So, via the image, we are reflecting on that very important fact that we sometimes overlook: it is important to fight injustice, but it is often fun, too!

Many of us know this at a personal level, in that we meet some great friends in campaigns, and we meet some really decent comrades. But joining with others, taking part, enjoying participatory democracy, we get to live life. So the book is a celebration of rebellion and the rebellious way, too.

Q: Has the book had an impact on the original issue at Kinsale?

A: Locally it has revived interest in the issue at the Old Head. With the passage of time, the loss of this amenity is felt more acutely. There is a sense that the community was “robbed,” and in a way it was. Other cases have also emerged. For example, Donald Trump has a golf course that is involved in controversy in another part of Ireland. There is a golf course in Scotland with a similar tale of woe to tell, also linked to Trump, I think. People have told us about other cases similar to ours that are really about the same type of thing: the greedy one percent taking away from the public space. So it has brought an awareness that what happened at the Old Head is about a lot more than just something in our locality.

Another interesting aspect has been the positive response from many of the activists from the campaign. They have really helped to promote the book. I think many of them are proud that their fight has been celebrated with a book of its own.

Q: Some final points?

A: A couple that are related, I suppose. Firstly, we have to play the long game if we want to change the world. I know some ask, is there time? Well, we need time, too. There is a war of ideas out there, and neoliberalism is very pervasive. We need to get in there now. Books are one way of doing that because books are powerful. That has been known from time immemorial. So our book, The Worms that Saved the World, is part of the long game. We want to influence young people and have them think early on about the idea of standing up for their rights.

But let’s go a step further and ask, what do you do about your rights if the authorities and the courts say no? If they say to you that your rights don’t matter. Our book goes into that, and it is unequivocal: if you rebel, think about how to win and what winning entails. Educate, spread your ideas, and build support. It’s one of the lessons that emerged from losing at the Old Head of Kinsale. We didn’t do enough of that before the crunch came in the fight there.

At the very end of our story, the worms celebrate and they say, about their victory, “We did it together.” That says it all.

The Worms that Saved the World, by Kevin Doyle and Spark Deeley, is available from AK Press here: https://www.akpress.org/catalog/product/view/id/3217/s/thewormsthatsavedtheworld/

Kevin Doyle is a writer and activist from Ireland. His debut novel, To Keep a Bird Singing, is published by Blackstaff Press (Belfast). At the turn of the millennium, he was active in the campaign to defend the public’s right of access to the traditional walkways on the Old Head of Kinsale. That campaign and his daughter Saoirse’s interest in garden worms inspired this story. He is also the author of many articles on anarchism and the anarchist tradition, and teaches creative writing in Cork.

Born in Birmingham, Spark Deeley now lives in Cork, where she divides her time between professional art practice and community art projects. Her first book, Into the Serpent’s Jaws, an illustrated fable, was published in 2007. This was followed by Do You Remember Me?, an illustrated audiobook created with musician Catherine Cunningham. She has also facilitated the production of two volumes of art and writing by community groups in Cork: Knitting for Squids and The Light of the Lantern.

This piece is from Perspectives on Anarchist Theory‘s “Beyond the Crisis” issue, available here from AK Press: https://www.akpress.org/perspectivesonanarchisttheorymagazine.html

1 thought on “<p>Direct Action for Kids, By Kevin Doyle</p> <h4>with illustrations by Spark Deeley</h4>”

Comments are closed.