By Bender

Translated from German

“They got gloves, they got sticks, they got masks, they got everything:

An-TIFA.” (Donald Trump)

First, we need a short explanation of the term fascism. It’s important to note that the German Nazis never called themselves fascists. The term came from the Italian fascists and the movement of Mussolini, and although this was the prototype for the German Nazis, Italy was an enemy of Germany during the first World War, and therefore the German Nazis identified themselves as National Socialists. Besides this terminological difference, there are some big differences in their ideology, as well. In particular, in the essence of national socialism you can find anti-Semitism on the one hand and the idea of a “Volksgemeinschaft,” or blood-and-race-based nationalism, on the other. The term antifascist, however, was used by both Italian and German Communists simply because fascism first began in Italy. In the following discussion, both terms, fascism and national socialism, will be used quite equally, but it’s important to make clear that German national socialism is a particular and “worse” political form.

Before we look at the autonomous way of organizing, in general, and of organizing autonomous Antifa, in particular, we have to look at its two forerunners in Germany: the historical Antifaschistische Aktion of the 1920s and 30s, and the New Left after 1968.

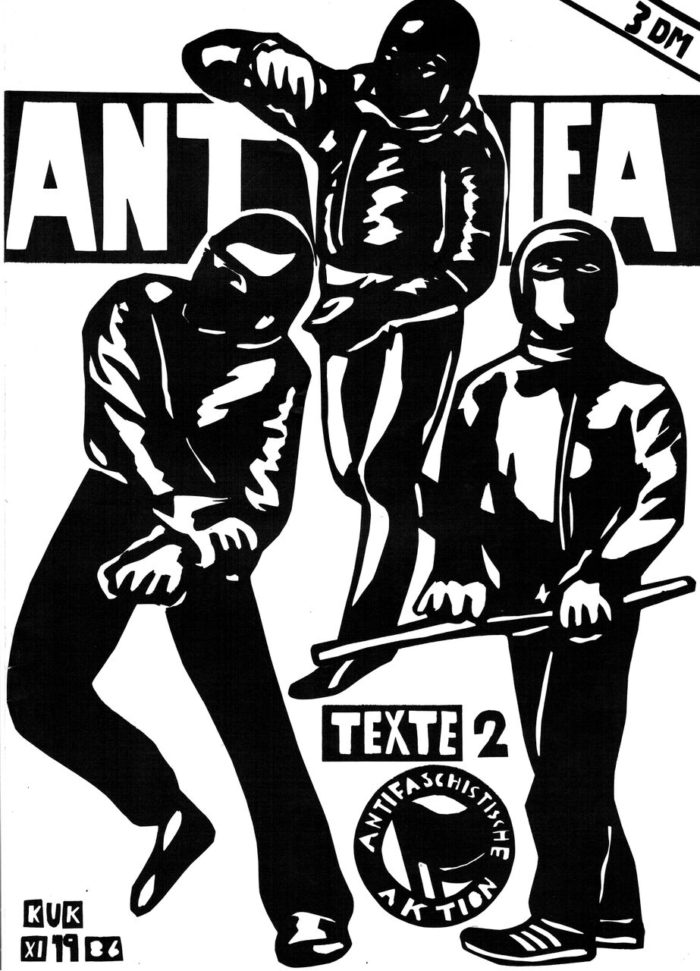

Antifaschistische Aktion in the Framework of Communist Party Politics

The historical Antifaschistische Aktion was built in the phase when fascism first became a mass movement and was officially claimed in 1932 by the Communist Party, one year before national socialism took power in Germany. While Antifa’s contemporary symbol is a red and a black flag, it was originally two red flags, symbolizing a united front between Social Democrats and Communists against national socialism. This unity was necessary, and in fact came much too late. After the First World War and the Russian Revolution, there was a split inside the labor movement into the Communist and Social Democrat parties. The radical wing around Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht left and built what later became the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Directly following the war, they tried to drive the so-called November Revolution of 1918 in the direction of a socialist revolution, which, for the Social Democrats, went too far. The Social Democrats then used the right wing corps to beat down the revolutionary uprising. Thousands of revolutionaries were brutally murdered. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were arrested and shot to death on the night of their arrest, and the dead bodies were thrown in a canal in Berlin. All of that happened under the Social Democrats of that time.

After this betrayal, Communists and Social Democrats remained political enemies, incapable of working together—until the National Socialists came to power. The reactionary forces—and later the National Socialists, of course—blamed both for losing the First World War and dividing the nation. Despite their common enemy, or even because of it, the two primary forces on the left fought against each other instead of fighting together against national socialism because they shared the same wrong analysis. Neither took the mass character of the upswell seriously enough, nor its anti-capitalist orientation, and both saw in national socialism only a symptom of capitalism in its final crisis. Therefore, for them, the main question seemed to be: Who will take over the situation? Who is best prepared for the final crisis of capitalism, the Social Democrats or the Communists?

Because of the split after Word War I into a Bolshevik Communist and a reformist Social Democratic party, but also because of their equally false analysis of national socialism, the Communists called the Social Democrats “social fascists,” while the Social Democrats called the Communists “red fascists.”

By the time Antifaschistische Aktion finally came together in 1932, it was all too late. And although the Antifaschistische Aktion initiated by the Communist Party was meant to build a united front, they intended the unification to be under the leadership of the Communist Party and their ideology, which was under the influence of the Stalinist Soviet Union and the Communist International, built after World War I.

There are three points to be learned from the failures of this first historical era:

1. Regarding praxis against fascism, some kind of political unity is needed, be it by a “popular front” with centrists and liberals or in a “united front” with left forces only.

2. This leads to the second lesson, which concerns the false analysis of the main antifascist forces of this time. Fascism can, in fact, be seen as a reaction to capitalism in crisis, but this crisis in not the final one before the rise of socialism. Instead, we must take two characteristics of fascism seriously: first, the mass character of fascism (and its mass basis also in the subalterns and the working class), and second, its own anti-capitalist orientation. Fascism exerts its attraction on the masses precisely through its own form of anti-capitalism.

3. This reaction to capitalism and its contradictions and crisis, however, is a limited form of anti-capitalism. The connection between capitalism and fascism is not that fascists and capitalists simply go hand in hand, or that the capitalists use the fascists politically for their economic interests, or that the fascists simply manipulate the masses or the population. This kind of functionalistic and economic view was a weakness in both the Communist Marxist and Social Democratic analyses.

The Beginning of Antifa Organizing in the New Left after 1968

The real forerunner of the autonomous Antifa is the New Left, which began in many capitalist countries of the West after World War II. The beginning of the so called New Social Movements, from which the autonomous movement of the 1980s would be one result, was “the long year of ’68,” which in Germany was perhaps best characterized as an “anti-authoritarian revolt.” We also have to remember that the “year of ‘68” lasted much longer than only one year, politically speaking. The movement right after ‘68 had reached a kind of exhaustion, and they were already asking themselves how to organize a movement in decline.

As often happens in the discussion of organization inside the radical and revolutionary Left, there were two poles: one around the concept of organization and party, the other on self-organization, spontaneity, and movement. The same tension played out in Germany when, after the “moment of the movement” of ’68, the 1970s followed a more party-driven orientation. The 70s were the decade of the so-called K-groups, various Communist groups with often large memberships, all aiming to become a mass party. It was like the last episode of the history of Communist parties. When the first episode ended in the tragedy of the party-state, this episode was the farce of Communist groups run by students with no impact on the working class, yet exerting great influence for new forms of politics and new political issues. It was in this context of the K-groups that, in the mid-1970s, the first political actions—and the term Antifa—appeared. The first new generation of Antifa grew from within the K-groups.

But just as the student movement went into crisis at the end of the 1960s and transformed itself in the decade of the Communist groups, these K-groups also went into crisis at the end of the 1970s. The situation split into two different orientations to organizing: the Green Party on the one hand, and the autonomous movement on the other.

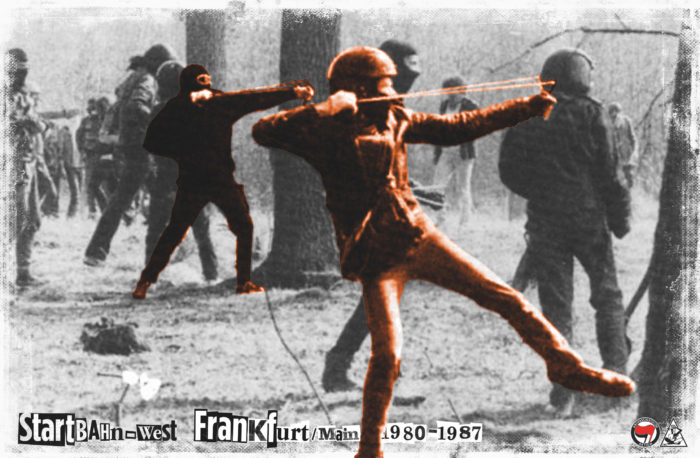

Autonomous Antifa of the 1980s and its Generations: Revolutionary, Pop, and Post-Antifa

With the Green Party and the autonomous movement, we see again the two poles: party on one side, and self-organizing, networking, and an explicit politics against all kinds of state apparatus and institutions on the other. Like the radical and anarchist Left in the US, the autonomous movement of the 1980s in Germany was organized around squats, autonomous and self-organized youth centers, and independent, non-commercial infrastructures like infoshops, leftist book stores, and other sites of subculture. This model of politics was based more on the plenum and consensus than on decision-making through voting and by majority. Politics functioned more by events and campaigns than by following a program or single theory. The movement was more interested in practical action than in theoretical debates, and it was, generally speaking, more a lifestyle-driven youth movement than an organized and well-reflected intervention in the political discourse.

The autonomous style of politics pioneered not only the organizational styles of non-hierarchical, non-dogmatic, and project-based networking (what could be considered post-Fordist or even neo-liberal organizing), but also the themes and issues of struggle were somewhat decentralized and widespread. Anti-war, anti-atomic energy, squatting and struggle for autonomous free spaces, punk music and independent labels, anti-imperialism, and solidarity for political prisoners were all part of the work. Anti-fascism was only one of these issues, and not the most important one. Also, the fascist movement in the 1980s was very weak, and there was still something like a left hegemony among the youth.

All this changed at the end of the 1980s. Like the student movement of ‘68 and the K-groups at the end of the 1970s, the autonomous movement also lost momentum at the end of the decade.

In general, one can understand the autonomous movement as a kind of (self-)critique of the Fordist era, the attempt to overcome it and with that part of the movement into post-Fordist ways of working, living, and making politics. The crucial terms, and the attitude of politics and lifestyle in the radical Left were principles like self-determination, self-realization, autonomy, the critique of all forms of authoritarianism, the deconstruction of all forms of representation, and a general resistance against the state and the classical political parties. Some of these critiques have become part of the neo-liberal mainstream; some have been overtaken by anti-capitalist forms of populism; some have been adopted by the neo-liberal “self-improvement.” In any case, the autonomous movement had to change with the neo-liberal, post-Fordist, and finance-capitalist flexibility and individualization of society, and the restructuring of the state, with its withdrawal from social welfare, social infrastructure, and an active labor market politic.

On top of these broader changes, there were a number of particular reasons for the exhaustion experienced by the autonomous movement at the end of the 1980s, which laid the groundwork for its evolution:

- Social ghettoization;

- Poor public relations and media-politics;

- The mainstream acceptance of some autonomous and subcultural lifestyle practices; due in part to a new neoliberal form of governance;

- The crisis of the so-called civil society;

- The decline of the various Teilbereichskämpfe, or struggles on various single issues like opposition to war or to nuclear energy;

- The implosion of real socialism and the collapse of the Berlin Wall, which changed the situation worldwide; and,

- New laws created especially against the movement, for example those directed against militant demonstration and the black bloc.

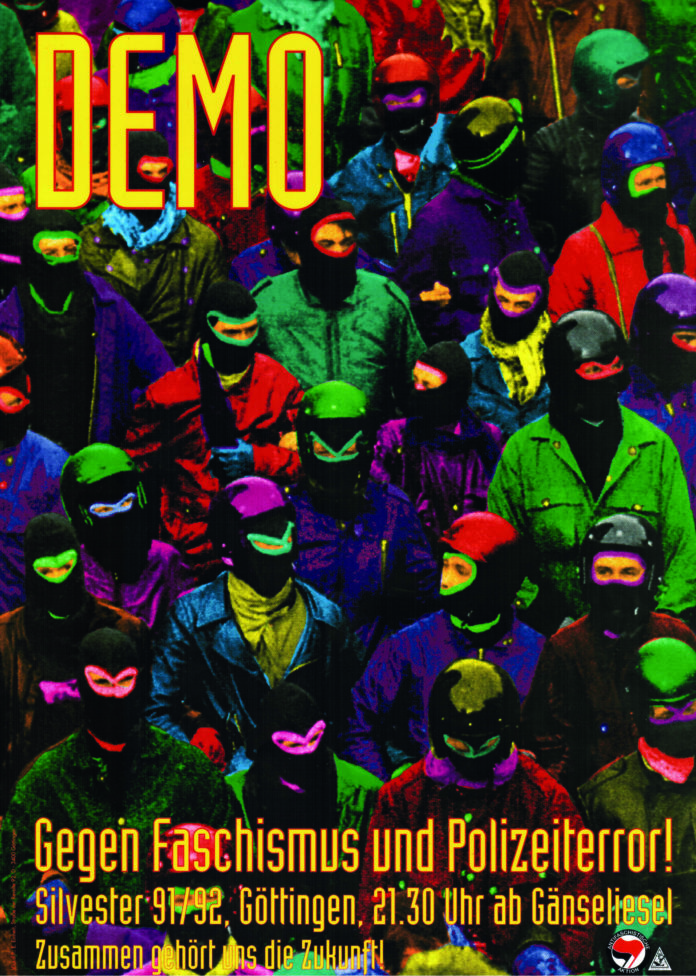

It was in this context that the question of how to organize arose again. This was discussed in the autonomous movement and posed from one of the first and most exposed autonomous antifascist groups, the Autonome Antifa in Göttingen, but also by the Berlin group For a Leftist Current (FelS), which initiated what became known as the “Heinz-Schenk Debate.”

The organizing debate refers on the one hand to the very dogmatic theory and praxis of the K-groups in the 1970s and tighter organization in general, and on the other hand, the problems and the strengths of autonomous self-organization of the 1980s. The main problem seems to be the lack of commitment and the unaccountable or non-binding character of the structures. They weren’t really structures, but rather informal connections, officially non-hierarchical, but with internal and very informal hierarchies.

Another problem was that the movement had no continuity on a personal level. It always depended on enthusiastic, experienced, young organizers who would exploit themselves for the movement for a certain period, and who could live an autonomous lifestyle. In other words, there was no place for people with children and family or with a 40-hour-per-week job. This problem only intensified in the 1990s with the advance of the neoliberal restructuring of society.

Together with this lack of structure and lack of personal continuity, there was no continuity on the level of content. There was no transmission of experiences from one generation to the next, and although there were lots of endless discussions, they did not necessarily contribute to theoretical development. The same discussions were repeated over and over, and if anyone wanted to engage in theoretical or critical debate—like about political economy or capitalism on an abstract, systematic level—they had to search for it somewhere else.

In short, the keywords in the debate were Verbindlichkeit und Kontinuität, commitment and continuity: there was the need for continuous and binding structures. The most important step was to get organized in groups with regular meetings, a common basis of understanding, common goals, a clear name, approachability for others, and a capacity and willingness to build and maintain alliances; we needed groups that represented their positions in public via a regular practice that was open for participation.

Another important point was temporary alliances with other groups outside the autonomous movement like trade unions, the Green Party, the youth organization of the Social Democrats, and so on. But as important as these alliances were, equally crucial was the necessity to maintain our positions and our forms within these alliances, to have—at least on a symbolic level—an autonomous standpoint and a radical expression, like using black bloc tactics at demonstrations.

This leads to another point: we needed better public-relations and a concerned media politics, which meant not really working together with the mass media, but using them to produce optics for the public, which nowadays has become a “politics of the spectacle.”

Concerning all these important points—fixed groups on a common basis, media politics, politicizing the youth, making alliances with reformists, having a concrete praxis—for all these points the best topic seems antifascism. We have to remember that autonomous politics were always conceived around concrete struggles like squatting houses or resistance to war or nuclear power production, etc., but the idea was always to fight for more and to use such politics to politicize people and to radicalize both the struggles and the people who were already involved in them. Antifascism was one of these struggles that stood for anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism, and an anti-state orientation, in general. It was one important issue the autonomous movement had in common that could be the starting point for alliances with others, organized around concrete events like blockading fascist demonstrations. A lot of people who perhaps would have been part of the autonomous movement in the 1980s are now organized in antifascist groups inside of what was left from the autonomous scene.

These groups were usually internally organized in working groups with different issues, even if all the politics happened under the common term Autonome Antifa. The idea was still to use one single issue and one single struggle to stand for a critique of capitalist society in general, and to radicalize other people and the larger political context via Antifa. Discussions within this framework led not only to a new style of politics in single Antifa groups, but also to an attempt at a broader kind of organizing.

The two tendencies in tension within the discussions about how to organize were also found in the debate about broader organizing. The conflict was, in short, the question: “organization or organizing.” The groups that advocated the building of a nationwide organization between Antifa groups initiated the so-called Antifaschistische Aktion/Bundesweite Organisation, AA/BO. The AA/BO started in 1992 after a big meeting with a lot of interested autonomous groups as well as a lot of critics. One result of these critiques was the more network-based meeting, Bundesweites Antifa Treffen (BAT), which started two years later as a reaction from those who saw the same need to organize but wanted to take other forms. While the AA/BO was focused on a common praxis and unity under already well-organized antifascist groups, BAT emphasized openness and a more platform-based and discussion-oriented style of organizing.

The common goals inside the AA/BO were to take revolutionary and anti-imperialist antifascism as the common praxis. The short-term goals were to build an infrastructure for a nationwide organization with a common program, especially in the form of campaigns organized and coordinated together.

One important point is that anti-fascism initially was chosen not because the fascists were strong at the time; it was chosen for political reasons. Among all the various issues of the 1980s, antifascism continued to feel vital and strategic. It was the best way to politicize younger and mainstream people, to radicalize the already politicized, to receive mass media coverage, to organize concrete actions, and to legitimize a certain level of militancy. It also presented an opportunity to be radical in theory, broaching the connection between capitalist crisis, a socialist alternative, and the option of a fascist “solution.”

However, these theoretical and strategic considerations where overwhelmed and run down by the implosion of the “real socialist” states and the East German GDR and the process of German re-unification. In the early 1990s, this ushered in a general climate of nationalism and an enormous boost of fascist groups, fascist attacks, and actual pogroms. The attacks resulted in dozens of people killed, and so Antifa then became a question of self-defense, in particular in the former GDR, where the situation is still much worse today. This general climate and the necessity of self-defense in the beginning of the 1990s, which we called Die antifaschistische Selbsthilfe organisieren (“organizing antifascist self-help”), is quite similar to the situation in the US right now with Donald Trump.

Along with their approach to organizing, Antifa meant always more than fighting against Nazis and their infrastructure. Apart from the fact that most Antifa groups worked on different issues (like the autonomous movement before), actions under the name of Antifa were also key for anti-capitalist politics in general and had a militant and revolutionary attitude. Thus, this generation of autonomous Antifa of the 1980s and 90s is considered “revolutionary Antifa.”

So, while the first generation of Antifa came from inside the K-groups from the mid-70s to 80s, the second generation was developed within the autonomous movement from the mid-80s on, which has defined its subsequent revolutionary attitude. We can further differentiate two next phases or generations of Antifa politics again with a decade each. The third generation we could call “Pop Antifa.” “Pop” simply means that cultural forms became more important and replaced the old autonomous style: sports clothes, techno acts during demonstrations, stylish layout and outfits, using new technologies like computers and the Internet, working out and being in good shape were all part of the scene and the practice. It was not only a new look, but also a new attitude, a desire not to take Antifa not too seriously; Antifa is necessary and always right, but the Pop period from the mid-90s until the middle of the following decade showed it can be cool even if it’s not directly revolutionary.

The fourth generation, the period in which we are now, is not “pop,” but “post-Antifa.” “Post” means that, while the connection is still there—nothing new or different has replaced Antifa—the actual politics don’t really run under that label any longer. The political work is more about organizing, also organizing theoretical debates about capitalism, crisis and precarity, about commons and communism and so on. These groups are often also called post-autonomous.

Perhaps there is a “fifth generation” or phase. Somewhat unintentionally, Antifa has become an international label for this kind of politics outside Germany, as well. Now you see not only the symbol and the slogan everywhere in Europe but in the US; comrades in other countries also see the need for this form of antifascist engagement. Perhaps Antifa is now happening more outside Germany than within.

The Critical Core of Autonomous Antifascism

Regarding the theoretical and strategic considerations of Antifa in Germany, it is important to emphasize that while antifascism is fighting against fascism on the streets and in the parliament, it is not a reaction to what fascists are doing. One reason for this is that antifascism is criticising the conditions behind fascist ideology, so it is a critique of the capitalist mode of production, its contradictions and crises, but—and this understanding of fascism differs from the tradition of Marxism and party Communism—also of the ideological reactions inside capitalism. The second reason is that, if certain politics against fascists are unavoidable, like counter-protests or reactions against fascist attacks or murders, antifascism has to follow its own anti-capitalist agenda and define its own goals.

We can locate this critique precisely between two blind spots. Antifa addresses the blind spot of both liberal-democratic and traditional Marxist analyses of fascism. In the end, both have the same blind spot: Why does an enlightened modern society, even a liberal democracy, turn into its opposite, into fascism, war, mass murder, and extermination?

Democrats and liberals and mainstream society can only address this tendency as if it comes from outside. Their key terms therefore are extremism, radicalism, and totalitarianism. The democratic identity can only externalize, and maybe must externalize, its own immanent turn to fascism as something that comes from outside and happens like a foreign “other”—while it is in fact nothing other than liberal democratic capitalism itself. This is how liberal democracy makes its own inner logic its very own blind spot, while Antifa is based on the insight and the experience that the masses who join fascism are coming from precisely mainstream society. Simply put, if things become critical, the democrats and liberals of today can become fascists.

Marxism sought to reconcile this but failed by delegating the interest of the capitalist class to the fascist party. Marxism ignored fascism’s mass character, not understanding that fascism maintained for the masses a true and quasi objective class interest, which is ultimately betrayed and manipulated by fascist ideology. For Marxists, the masses’ class interests can only be addressed by Communist politics. Traditional Marxism ignored the mass character of fascism in its epistemological, ideological, and psychological dimensions. It hence has no adequate understanding of the irrational or corrupt economic dimension in fascism, which again is the blind spot of how economic rationality can turn into its opposite, into mass destruction and even in a holocaust. This may not follow a pure economic exploitation or interest, even though it still has to be explained by capitalist categories.

To understand this blind spot of both poles, the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School was very important for Antifa in Germany. Like Antifa, Critical Theory located its critique in critical distance from both liberal democratic and traditional Marxist theory. For example, Moishe Postone’s analysis of anti-Semitism in Germany was very important in the 1990s, especially by analyzing abbreviated, short-sighted forms of anti-capitalism, which we could call a structural anti-Semitism.

In particular, the discussion around the importance of anti-Semitism and nationalism (one outcome was the so called Anti-Germans) in the 1990s was not only important for the understanding of national socialism. It also turned around the understanding of capitalism in general, which is not only problematic by its “normal” crisis, exploitation, inequality, and so on, but by the ideological mass reaction to this. So, in a way it was necessary to defend capitalism and democratic standards against attacks by incomplete forms of anti-capitalism that opposed a productive and useful labor against a finance capital, in which was seen a Jewish principle.

But still—the real object of critique and duty for autonomous antifascists is the inner connection between capitalism and fascism and other authoritarian forms of politics, and the turn from liberal democracy into its own other. The same goes for other forms that the radical Left is criticizing, like we have in identity politics. The connection between capitalism and sexism, racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia and so on needs to be made explicit. To critique all these inner connections to capitalism on a theoretical and practical level is, in the case of Antifa, the most urgent task. Here the connection of capitalism with repressive and authoritarian forms is not only more drastic, but different ideologies like racism, sexism, nationalism, and homophobia overlap.

The limits of this antifascist critique are the same as in other issues. People freely admit that fascism is bad, and so are other forms of oppression. But they insist that liberal democracy, law and order, the state and its institutions, discussion, and education can protect us. Capitalism is not responsible for these forms.

And that’s all true. And nevertheless, we must insist that we can’t talk about these forms without talking about capitalist forms and how they, besides its “pure” economic inequality and associated problems, also produce ideology. And, we must use this “pure” capitalism to criticize its abridged, ideological forms of anti-capitalism like in national socialism or in right-wing populism. So, our critique of capitalism is also that it produces its own abridged ideological understanding. The devastation of neoliberalism is not only economic, but is also social, and the immiseration and the poverty that capitalism leads to today is, in our societies, less economic, but more social, cultural, and political.

To summarize, it’s not an exaggeration to say that, in Germany more than in every other country, the latest generations of the radical left were politicized by the two political issues, a “normal” anti-capitalism like in other countries, and by the particularity of national socialism and the holocaust, interpreted from the radical Left as one reactionary answer of capitalism inside capitalism, an anti-capitalist revolt or even a revolution inside capitalism itself. But national socialism was also a total failure of the working class as well as of the population as a whole, creating in the German radical Left a great distrust against any forms of populism, nationalism, and short-sighted anti-capitalism, together with a consciousness of the importance of anti-Semitism not only for the whole idea and ideology of national socialism, but for the way in which capitalist modernity and its crises were “resolved” by masses or at least main parts of the population in fascist countries.

The one lesson we always have to keep in mind is: We can’t be safe! Democracy and the population, however liberal they might be, can be something totally different tomorrow, should the conditions arise. There is no protection. If not for our engagement, no one will do it for us, not the police, not the secret service, not the parliament, and not all the democrats, because we can’t be sure what they will be or do when economic growth stops, when a rich and well-situated country like Germany goes into a crisis or state of emergency. We should be aware that it is more likely that the masses, including the liberal democrats, will go instead in an authoritarian, populist, racist, nationalist, fascist direction rather than in a socialist or progressive, emancipatory one—just as has already happened in Turkey, Hungary, Poland, in the Middle East after the Arab Spring, and, of course, here in the US.

To be clear: of course, the democratic state and its institutions are something totally different than fascism in power. And of course, there is repression and also effective repression against the various forms of fascism by the state. But there is no need to be confused, as it is exactly this repression that turns out to be the problem: the state can only see and treat fascism as a criminal problem and something that comes from outside. It never enacts repression as an antifascist State or with an antifascist identity or constitution, nor can it act against the capitalist conditions. The same goes for every single element in the state-apparatus: police, secret service, public ministers, and mass-media. Of course, they all are against fascists and fascism, but neither as anti-fascists nor embedded in a critique of capitalism. In short, there is no antagonism between fascism and liberal democracy.

This relationship between Antifa and liberal democracy can be brought to the point with one simple quote. When, after the second World War and the victory over national socialism, the German parliament spoke about the Grundgesetz, the new German constitution, a member of the Communist Party (which was banned a few years later) said, “Today we do not vote for the new constitution. But one day, we will be the ones to defend it.”

Bender has been involved in the autonomous movement in Germany since the 80s, both in Autonome Antifa (M) and the nationwide organization AA/BO (Antifaschistische Aktion-Bundesweite Organisation). He’s taken part in all the “big events,” like the G8 and G20 protests and annual May Day actions. He is currently involved with TOP (Theory, Organization, Practice) in Berlin, which is part of the national organization Ums Ganze. Ums Ganze, an alliance of anti-nationalist, post-antifa groups that focuses on the critique of capitalism directly, and is part of Beyond Europe (beyondeurope.net)

This essay is from Perspectives “Beyond the Crisis” issue.