Anyone who has been involved in a group project that strives for consensus knows that working shit out together is hard. It’s challenging to collectively do the work of assessing options, making decisions, and executing plans that sometimes carry real individual and collective risks, even when members of a group are aligned through culture, ideology, issue, place, or common interests. And it sometimes feels impossible when there are cleavages along lines of race, gender, class, experiences of trauma, generational differences, and other differences within a group. And where even one person has shifting moods and states of mind, any group of people contains a confounding palette of shifting unconscious drives, implicit biases, and personal idiosyncrasies that can harden into a clash of personalities or factionalism that has sunk many a revolutionary project, cooperative, band, collective, or community gardening group.

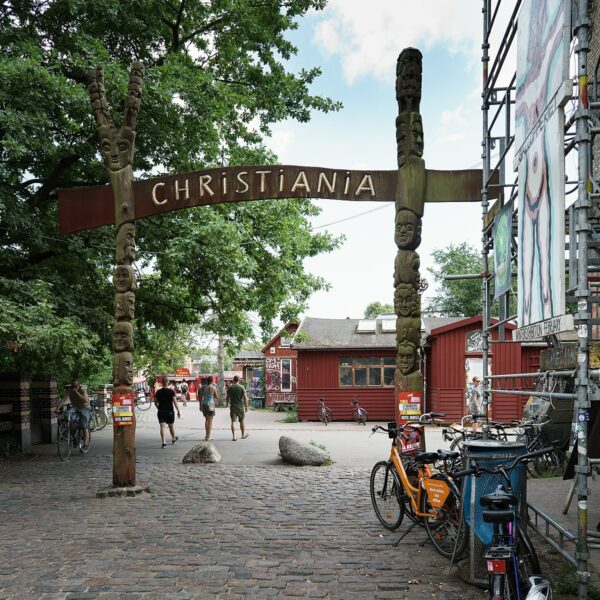

The Freetown of Christiania, in Copenhagen, Denmark, has been practicing a form of medium-scale consensus democracy for half a century. This look at Christiania’s system of direct democracy is written with the hope that considering some of the social and political qualities that contribute to the durability of Christiania’s sustained experiment in direct democracy might be useful to other groups and places practicing their own forms of horizontal self-governance.

Christiania was founded on a late September morning in 1971 by a group of “Slumstormers … a mix of students, leftist activists, drug offenders, and other young people”[1] who were squatting abandoned buildings slated for demolition under urban renewal plans in the adjacent working-class neighborhood of Christianshavn. The group decided to formalize the community use of a decommissioned military barracks where for some time neighbors had cut holes in the fence to picnic and play. The Slumstormers squatted the buildings and grounds, declaring on a hand-written note, printed in an alternative newspaper, that “[t]he aim of Christiania is to build a self-governing society, where each individual can unfold freely while remaining responsible to the community as a whole.”[2]

Fifty years later, Christiania is a vibrant community and urban space full of contradictions. A visitor will find independent and community businesses and cultural venues, an illegal hash trade with connections to biker gangs, nonprofit collectively owned housing for close to a thousand people, internal employment opportunities, social services, a health clinic, schools, a sauna, religious spaces, meditation centers, and arts, cultural, and organizing spaces.

With well-maintained urban green space, restaurants, and unusual venues, Christiania has become a major tourist destination, as well as a party zone that manages a constant flow of outside visitors. Remarkably, Christiania remains a self-governing participatory democracy, managing a significant budget, organizing housing and community improvements, trash collection, and interpersonal conflicts and violence through a structured—although still informal—system of nærdemokratisk (close democratic) consensus-based decision-making.

I visited Christiania as part of the Christiania Researcher in Residency program in the summer of 2019, when I interviewed fifteen residents and members of the community about their experiences and thoughts, asking each how the consensus system at Christiania actually works.

Covering eighty acres of mixed-use buildings and parkland, Christiania is situated less than fifteen minutes walking distance from the ornate medieval buildings of the Danish Parliament. The oldest structures are beautiful, yellow brick buildings built along ramparts in the mid 17th century to fend off Swedish invasion. The combined area includes former barracks, apartment buildings, workshops, enormous halls built of brick and ship timber, DIY houses, and a system of trails that circle several ancient moats, winding over embankments and gardens. In 1972 Christiania was declared a “social experiment” by the Social Democratic government, and collective use fees were established, giving limited approval for the occupation. Successive Conservative and Social Democratic governments have since launched various legislative and law enforcement campaigns to end the social experiment of the Freetown, frequently entailing sustained periods of aggressive police actions.

In 2012, following a long and fraught negotiation process, the community of Christiania consented to a legalization agreement that restricts new development and imposes municipal regulations and oversight of building codes. Although the agreement increases costs and bureaucratic requirements, it manages to preserve Christiania’s self-governance[3] by codifying a system of collective ownership that includes stewardship incentives for residents to maintain and upgrade both private and common spaces.

Since it was founded, the community has been committed to pursuing a participatory democratic form of self-governance. Initially, residents of Christiania resolved to talk about all community issues in the Fællesmøde, or Common Meeting, before quickly realizing that it was too burdensome to discuss every single issue with the whole community. The Common Meeting was dissolved in 1972, and a more flexible and local system of “nested authority” was adopted, dividing governance into smaller units, with the Common Meeting serving as the ultimate governing body on issues relevant to all members of the community.

My intention is not to idealize the system that has developed at Christiania. It is a very particular and place-specific phenomenon, and Christianites speak openly about the considerable challenges facing the community. However, after fifty years, Christiania retains a structured and informal system of consensus democracy that manages a territory with buildings and land, enterprises and economy, a budget, and exterior relations with the Danish state, along with internal development, dynamics, and conflicts, at least reasonably well.

My interest in consensus and participatory decision-making is partly informed by my own experience in the legalized NYC squat where I live, and a lifetime spent in activist and community circles where consensus practices are the (sometimes messy and imperfect) ideal. I remain curious about, and sometimes perplexed by, the challenges of sustaining the horizontal and cooperative social forms that will be necessary for a fulfilling, peaceful, and meaningful life for our collective future. Informed by this personal experience, this essay aims to shed light on some qualities that seem to contribute to the sustainability of the consensus system in Christiania, thinking particularly about the social structures, practices, and resources that are available in the system.

I – Common Identity

Bøssehuset, literally translated as “faggot house,”—in reclamation of a former insult, like “queer” in English—was squatted by a few gay men after the founding of Christiania, and soon became the social center and organizing base for the Gay Men’s Liberation Front.[4] Stjerneskibet, or the Starship, run by Inuit people (or Greenlanders, as they are called in Danish), has a café on the ground floor where the air is thick with hash and tobacco smoke, along with the smell of spilled lager, while upstairs there’s a sober space that hosts board game and dart nights, and above a housing co-op with ten residences. There is a Buddhist center just off of Pusher Street, as well as a Christian group that hosts regular meetings. There are skaters, journalists, shopworkers, builders, plumbers, teachers, artists, and also those involved in the hash trade—some with two or three generations in the business—dressed in Euro street and hip hop styles.

Several of the Christianites I interviewed said something along the lines of “if you ask what Christiania’s about, you’ll get as many answers as the people you ask.” As a space that holds multiple identities that frequently come into friction, and sometimes violent conflict, Christianites continue to identify as members of a shared community. How is this shared identity constituted, and what can other communities or projects learn from it?

Black Sheep of All Classes—a Sense of Belonging

When I asked one of the founders of the radical theater troupe Solvognen about the glue that holds people together, she cackled, in a way that made me think she had said it before, “Black sheep of all classes!” She then went on to propose that Christianites are united in a shared identity as outsiders, outcasts, or inconvenient dreamers, all disaffected with their social status of origin. Several of the younger residents I interviewed described that they had felt somehow “set apart,” in their childhoods, before arriving in Christiania as adults with ambitious activist, artistic, or other aspirations to impact the community or use it as an organizing base, along with a desire to belong. The four relative newcomers I talked to all described a sustained sense of belonging in Christiania, even after their initial high expectations were mellowed in their experience actually living within a long-standing community with entrenched and hard-to-shift patterns. Although diverse Christiania residents may have different origin stories and individual ways of understanding themselves in relation to the community, they are each offered a sense of belonging and ownership within an open and shared collective identity.

First Principles

In response to questions about the origins of consensus decision-making in Christiania, a few of the folks interviewed suggested that consensus was aligned with interdependence beliefs associated with Buddhist spirituality. One person thought there might be a connection to consensus practices within lay councils of the Danish Lutheran Church, and others said that the commitment to consensus was an oppositional stance to Danish society at the time of Christiania’s founding, equally rejecting the coercion and alienation from day-to-day life intrinsic to capitalism and representative democracy, as well as authoritarian tendencies within Social Democratic, Communist, and other mainstream political parties.

One of the founders of Kvindesmedien, the women’s blacksmith collective, describing how the principle of consensus decision-making arose in the early days of dreamy, industrious, and ragtag pioneers, said: “we just knew we needed to talk to each other to reach a solution.” Almost all the Christianites I spoke with expressed complaints, fears, and hopes around the ongoing development of the consensus system. Agendas, minutes, and meeting notices show various initiatives, over many years, where Christianites worked to improve their decision-making processes, trying to make them more efficient and/or more meaningful to Christianites, within the framework of open and mutual deliberation. When a group of workers in Christiania’s “Economy Office” resigned in protest, they wrote that a person in leadership was limiting participation in decision-making, which they felt contradicted the community’s basic principles. In their personal critiques, even the most cynical Christianites grudgingly admire the simple political practice of people with shared interests talking to each other until they’re able to make decisions together.

Out Group Identification

The word for people living in Christiania, “Christianites,” is a geographic descriptor, sometimes used as a pejorative by residents in the adjoining neighborhood when referring to Christiania’s children attending local schools, or by the conservative media to galvanize the public for aggressive enforcement against them. The strong identification of Christiania with the hash trade in the early ’80s resulted in right-wing parties across the Nordic region labeling Christiania a “narco-swamp,” claiming open hash consumption served as a stepping stone to addiction for young people, and prompting regional campaigns to close Christiania.[5]

There are also affirmative out-group identifications associated with being a Christianite. As a place that is known for encouraging creativity, experimentation, and innovation, Christiania has received sustained attention nationally and internationally for its unique social system and cultural venues, as well as community approaches to urban space, planning, and sustainability—including community heating systems, waste management, and plant-based systems of sewage remediation.[6] Several of the younger folks I spoke with talked about feeling affirmed and proud of being members of the community when they receive curiosity and appreciation from non-Christianites.

II – Communication Practices

In his book Honeybee Democracy, neurobiologist Thomas D. Seeley proposes that a model of consensus decision-making can be observed in the process wherein honeybees make collective decisions about where to locate their hive with the turn of each season. Scouts go out into the surrounding environment, returning to the hive community with information about prospective new locations. The scouts communicate information about the qualities of the places they’ve found through an elaborate (and sometimes furious) dance. The process of collective evaluation can be seen through attrition or accumulation of support for a particular option, indicated by other individual bees performing their resonance with a particular option by mimicking the waggle dance of the scout, until there is overwhelming consensus to move in a particular direction, indicated by a mass of bees dancing their agreement, until the whole hive up and moves.

The process that happens between bees in a hive is similar to what happens in neurons in the brain of a human making a decision between competing options, [7] and is also similar to the most basic idea of effective participatory decision-making, with proponents of different options communicating the value of a preferred option, and the options being considered in a public process of evaluation, until consensus builds for one option over another. Seeley’s model of consensus, where a group deliberates over a range of options until overwhelming support accrues to a particular one, requires open dialogue and communication when applied to human communities. Thinking of Seeley’s model of decision-making in relation to Christiania, I was curious about the communication practices that support their system of consensus.

Forums for Open Dialogue Outside of Meetings

A visitor walking around Christiania will notice fliers posted on notice boards, taped in building windows, or stapled to utility poles, printed, or sometimes handwritten, with a few words at the top, a date, and a numbered list of items to be considered at an upcoming meeting. A sampling of fliers from when I visited in July 2019 had announcements for Area Meetings where topics under consideration included a collective water pump, reviewing building plans, introducing a summer guest, while promising coffee, cake, and a hyggelig (cozy) time. I also saw notices for a past series of Common Meetings on questions of meeting structure, when two meetings were scheduled: one for a presentation, questions, and information, and the following for decision-making.

These written and legible signs are expressions of the openness and accessibility of the process and agendas of community self-governance. A neighborhood newspaper, Ugespejlet (the Weekly Mirror), publishes meeting agendas, minutes, detailed budgets, proposals to raise resident use and other fees, and other information vital to the community’s practical governance, alongside short articles, announcements for birthday parties, calls to action, and other vital information.

The Weekly Mirror is also an important forum for open public discussion and debate on matters of policy, culture, interpersonal matters, as well as call-outs around public and private behavior. In reviewing a stack of the Weekly Mirror, I found a typewritten letter that had been published in which one person explained what he saw in a bar fight, asking one of the participants in the fight not to hold a grudge against him for intervening. A series of individual letters of resignation from workers in the Economy Group describe an undemocratic work environment; another defends the person who was accused of acting in an authoritarian manner. Multiple letters highlight what the writers view as being problematic about Christiania, including criminal elements and violence, nonparticipation in the Common Meeting, and yelling and screaming as unacceptable forms of debate.

I found a denunciation of racism when the community of mostly African bottle collectors were called in to a Common Meeting after a bottle collector was caught sexually assaulting a woman; the letter emphasized that the decision to call the bottle collectors in as a group was based on racist assumptions. Around the time Christianites were weighing complex proposed legalization ideas from the state, there were a spate of letters loudly arguing different options, with passion, logic, personal denunciation, while naming fears and hopes. The range of opinions and voices in the Weekly Mirror are all written from individual positions, reflecting the current experiences of the writers, and appealing to the sensibility, emotions, and logic of others in a plain-spoken and direct way. Taken together, the commitments to informational transparency and multiple forums for public dialogue reinforce the ability of Christianites to participate in both the formal and informal processes of decision-making. Support for options and proposals before the community can be considered, understood, and assessed by all members of the community, and consensus around a particular option can accrue, mirroring the way that honeybees make decisions to relocate their hives.

III – Scale and Distribution of Authority

Over the years, Christianites have developed a system of distributing authority that divides governance into appropriately sized and scaled geographic areas, with some delegated responsibilities, and builds in decision-making feedback loops to ensure that participation and influence is accessible to all members of the community on decisions affecting their lives.

Scaled Areas of Governance, with Some Delegation

When Christiania was first squatted, all issues were decided in the Common Meeting, that often had hundreds of participants, similar to many General Assemblies that characterized the US Occupy movement of 2011. However, it quickly became clear that a meeting open to all residents wasn’t the best forum for managing all the finer details of community governance. The Common Meeting remained the ultimate decision-making body on issues of interpersonal violence, negotiations with the state, and common funds and resources, while localized governance was devolved to ten Områder, or Areas, later expanded to fifteen. Largely determined by geography and ranging in number of residents from nine to eighty adults and children, Areas handle local issues, from choosing new residents to planning for Area-wide systems, like heating and sewage.They also manage local housing policy, as well as approving individual home improvement projects. Each Area appoints a treasurer, as well as resident and economy contact persons, who are all delegated representatives of Area interests to the Common Meeting and the other governance bodies.[8]

Over time, Christiania developed bureaucratic structures specific to changing organizational needs. The Contact Group is a delegate body formed to handle exterior relations with both the local municipality and the Danish state, the Economy Office liaises with internal businesses, and manages payment for construction projects, while the Building Office develops and manages large building and community development projects. All meetings with decision-making or advisory authority are scheduled and publicized, and any Christianite can attend any meeting. Additionally, there are review and ratification feedback loops between committees, the Areas, and the Common Meeting.

There are also a range of formal and informal committees, clubs, and working groups, including a Consensus Group that organizes discussions, info-sessions, and events, to promote fresh thinking on the consensus practices, or the Gardener Group, that takes care of plants and landscaping. When confronted with changing organizational needs in a growing and adaptive community, Christiania has generated bodies of governance made up of residents with the most direct interests in a particular area, from folks governing their neighborhoods to plant-lovers managing public green spaces.

Decision-Making Feedback Loops

Feedback loops for shared authority are built into decision-making processes. Low-interest rate home improvement loans for individual Christianites are first approved by an Area, then sent to the Building Office and the Common Meeting for review, then returned to the Area for final approval and oversight. When the community needs to discuss urgent decisions, for example in 2011 when very contentious questions related to the legalization process were being considered, Area meetings are called to ensure empowered and current feedback to the Common Meetings. Area meetings also regularly feature report-backs from representatives of the Common Meeting, the Contact Group, and other groups.

Additionally, Areas and Common Meeting are empowered to call in people or group representatives to discuss serious issues, including accusations of interpersonal violence and sexual assault,[9] as well as more day-to-day questions, like calling in a representative from the Gardener Group to discuss some rogue gardening that’s been going on without input from residents. Decision-making feedback loops between local areas of governance, the Common Meeting, and other committees and groups, allow everyone to deliberate, modify, and consent to decisions made concerning both their direct environments, as well as the wider community.

IV – Direct Action and Individual Initiative

One of the foundational stories of Christiania is the “Junk Blockade of 1979.” When Christiania became a haven for heroin sales and use during the ’70s, a large group of Christianites planned a sustained direct action campaign to evict all heroin users and dealers, requiring proof of attending detox and rehab for any who wanted to rejoin the community. Any powder and other hard drugs were banned from Christiania, which remains militantly true today.

In 1986, a group of women Christianites initiated a direct action campaign to push a gauntlet of Christianite hash dealers away from the main entrance and agree to restrict hash sales to one specific area, now called Pusher Street. In 2016 a cycle of clashes between police and dealers on Pusher Street culminated in an incident where two officers were shot, and the shooter escaped, only later to be found and killed by police. The following day some Christianites organized to remove the stalls that had been built by the dealers, which had allowed the concealment of weapons. As a result of the shooting the community at Christiania strengthened the agreement with dealers, preventing the erection of enclosed huts and reinforcing restrictions on where dealers can set up.

Sometimes, the community’s direct action takes more poetic forms. The lakes of Christiania are maintained on the initiative of the community, providing a green haven to city-dwellers as well as over 112 different bird species. The lakes are dotted with small hand carved and painted sailboats that trace slow figure-eights around a fixed anchor in a light breeze. Crafted by a few individual Inuit, or Greenlander, Christianites who live at Stjerneskibet, the Greenlander house, the miniature sailboats are an aesthetic practice and personalized intervention in the shared space.[10]

Direct action has also been a tactic used between groups of Christianites aiming to influence each others’ behavior. When individual non-payment of use and electrical fees started causing complications and financial burdens on the whole community, a group of Christianites called multiple meetings to address the issue, until, frustrated by individual non-compliance, they temporarily cut services to those who refused to pay, as a strategy to get them to understand the seriousness of their concerns, and to bring them to the table in the Common Meetings.[11]

Sometimes the direct action and individual initiative is a tinkering and experimentation that leads to systemwide changes. Several folks spoke with a mix of admiration and envy of the heating system that was installed in one of the Areas by an intrepid and handy Christianite who researched, designed, and implemented a highly efficient monitoring and regulation system that calibrates heat demand and supply in real time—reducing costs, energy usage, and providing a model for other Areas interested in reproducing the system.

A vision of space for individual development within the context of community responsibility was embedded in the original principles of Christiania, and plays out as more of a cultural and social quality than a hard rule. However, sustained attention to supporting individual expressions are embedded within, and accountable to, community needs and this is important to the healthy functioning of the consensus system.

V – Urban Autonomy

Situated in a former military barracks that was originally ringed with walls and fences, Christiania has the advantage of being a bounded space that feels separate from the surrounding neighborhood and the wider city of Copenhagen. Additionally, although the community has developed, there remains a mix of high to low density housing, as well as common parkland and open space, which allows room for Christianites’ different social and spatial preferences, promoting a common interest in shared governance of private and public spaces,

Space to Defend

In 2011, the Danish government gave residents of Christiania an ultimatum: agree to a privatization deal proposed by the central government or face eviction, one of several serious eviction threats residents had received over the years. The ultimatum came at the end of a particularly difficult period in Christiania’s history, after several years of violent police enforcement actions against the hash trade that often led to pitched street battles, along with persistent regulatory and civil attacks from the Copenhagen municipality, all part of a strategy to intimidate residents and push them towards privatization and the dissolution of their community. During this period, it wasn’t unusual for Christianites walking their kids to school to be greeted by the smell of teargas lingering in the air.

In one meeting about how to respond to the ultimatum, someone proposed shutting Christiania down to the flow of visitors,[12] an action meant to emphasize the Freetown’s role in the social and material economies of the city, highlighting that Christiania is a territory where the gates can be shut.

Space to Organize

When I asked one of the coordinators of the residency program about the relationship between physical space and the consensus system in Christiania, he talked about the incredible benefit of having a variety of indoor and outdoor spaces to accomodate the different groups that meet to shape and make decisions about day-to-day life, from smaller and more intimate spaces for working-groups or committees, to mid-sized spaces that can hold the interim-sized groups that are important to keeping life and initiatives at Christiania moving, as well as the sprawling Grå Hal, the concert venue that has the capacity to host community-wide Common Meetings where there is space for everyone to unfold, express themselves, and work towards common solutions. Beyond space to meet, Christiania’s rich infrastructure of a range of interior and exterior spaces allows for theater rehearsals, banner painting, silkscreening, fundraising, yoga classes, meditation groups, holiday meal shares, and all the other activities that give meaning and opportunities for connection in day-to-day life.

Space to Live

Additionally, the territory of Christiania has a rich and varied geography, from areas that have urban density within the former core of the barracks, to areas that are more spread out and pastoral, including nooks and crannies for daydreaming (or hiding out), allowing for members of the community to decide how close they want to be, while remaining in community. One of the folks I interviewed mentioned in passing that more socially marginal members of the community tended to live on the outskirts of Areas, leaving them able to determine how physically and socially close they want to be to their neighbors.

VI – Permeable Relationships with Outside Society

Christiania is not a cult; it’s a neighborhood. While geography has allowed Christianites to physically close the space to outsiders in times of crisis, for the most part Christiania has remained resolutely open to visitors, with Christianites devoting personal and community resources towards showing the outside world the alternative society being lived there. Conversely, while it is possible for individual Christianites to mostly live the circuit of their lives within their neighborhood, all those I spoke with had a significant part of their working and personal lives outside the community, through career, projects, schooling, and other activities, creating a permeable and interdependent relationship with the surrounding society.

Let Them See

A few years after the initial occupation, the Danish Parliament decided to withdraw approval for the social experiment of Christiania and evict the adults and families living there. One community response was to invite a working-class Danish family to come live at Christiania for a week, accompanied by a filmmaker who made a documentary that was broadcast on public television. The Hansen family began the experience expressing support for the closure of Christiania, but ended the week of communal meals, workdays, and long conversations closer to the view that Christiania was an “experiment that should remain.”[13] The release of the documentary changed public opinion and diffused the political will for an eviction, laying the foundation for an ongoing practice of letting people in to observe the experiment of Christiania as it has developed.

Most visitors quickly get a sense of what draws non-residents to the area, including the car-free space and natural environment, beautiful buildings in a well-worn state, popular restaurants, a skatepark, run by Alis (a local skateboard and streetwear brand that builds skateparks in the developing world), and a range of venues and show spaces, including Nemoland, and Den Grå Hal, (The Grey Hall), which has hosted Bob Dylan and Rage against the Machine, and was an action center for climate change protests when the UN Climate Change Conference was held in Copenhagen in 2009. There are businesses like Christiania Bikes, a women’s collective metalwork shop, and, not least, the hash trade on Pusher Street, where these days dealers stand by individual bar tables with large umbrellas sheltering their hash and marijuana selection. Daily walking tours, hosted by a roster of Christianites, educate visitors about participatory democracy in the community, along with its institutions, histories, and sites.

The linking of Christiania’s participatory democratic practice with a sense of stewardship of the space, and an openness to the outside world, is found at the day-to-day level as well, which I encountered reading an issue of the Weekly Mirror, where a personal letter scolds someone who told a school group of kids from outside the area to go back home, saying “it’s just too weirdly hermit-like if we can’t tolerate Copenhageners, ladies with blue hair, school children, and Jutlanders using Christiania.”[14] Interestingly, the one area where Christiania maintains a strict privacy with regards to outsiders or visitors, including myself, is in their meetings, where journalists, researchers, and other observers are not allowed.

Show Them How It’s Done

In addition to inviting the outside in to experience the distinct physical and social environment of participatory democracy, for many individuals and groups, Christiania has served as an organizing space for actions and campaigns intended to impact the wider society, and individual Christianites are not discouraged from participating in life outside the community.

Solvognen, or the “Sun Chariot,” was an influential activist and performance collective that staged elaborate and confrontational public theater actions, including one anti-capitalist action week when groups dressed as Father Christmas paraded through the city and, in one action, invaded the main department store to hand out gifts to children in the spirit of Christmas season. This episode ended with the police beating a Santa Claus— accused of nothing more than simple act of direct redistribution—in front of a group of horrified children[15]—this is the noble origins of the contemporary vomit-fest known as Santacon. Activists from Bøssehuset and the Gay Men’s Liberation Front staged theater pieces and public actions in support of gay liberation in small towns throughout Denmark, and Pigegarden, or the Women’s Guard, performed subversive and colorful drum majorette routines at political and social actions. In addition to activist-oriented events, the Christiania-List has been fielding political candidates in local municipal elections since the mid-’70s, that are sometimes able to influence policy as a minority party in Denmark’s parliamentary system. And during the heyday of the BZ movement, a militant youth squatter movement in the ’80s and ’90s, Christianites were known for organizing support for embattled BZ’ers behind their barricades.

VII – Economy

The basic requirements of providing residents of Christiania with room to live requires an economy that collects and distributes resources to meet basic obligations to repair, maintain, and improve public and private spaces as well as keeping up with payments to mortgage holding banks, utilities, and the municipality. The economy of Christiania provides a material foundation for social life, along with collectively governed space and territory. This made me curious how the qualities of economic life in Christiania might contribute to it being a functional participatory democracy.

Pay as You Go

The first agreement made with the Danish state recognized Christiania as a “social experiment” while also determining collective use fees for electricity and water; creating a contract with the state that conferred a limited material legitimacy to the project. The community established a fælleskasse, or “common box,” to collect funds, at first an actual cigar box, that now funds a complex budget, pays for construction projects, waste management, maintenance, and administration, as well as collective taxes, fees, and financing payments. Although the expectation is embedded within a culture of social solidarity and mutual aid, each individual Christianite is expected to contribute equally to the baseline material needs of the community, in the form of a monthly fee that corresponds to their individual use of community resources, and is used to pay for community services they share, in budgeting and allocation processes they can participate in.

The fælleskasse is funded through the payment of brugslej, or “use-rent,” by individual Christianites, as well as businesses. In addition to a basic use-rent charged to every adult resident, there are additional use-fees for individually metered water and electrical services, as well as a square meter fee for individual living space that was added after legalization to account for increased costs of maintenance and debt service.

Collection of use-fees has not always been smooth, with individuals and Areas having at times been in significant arrears. In addition to being poor, some Christianites also have complicating substance use or mental health issues. A general fund to support individuals having a hard time meeting their use-fees is available, with requests made through the Area, and Christianites struggling to pay use-fees can be connected through neighbors and internal social services to fairly generous Danish welfare state benefits.

An Entangled Model of Collective Ownership

The 2012 legalization agreement is a complex arrangement between the state and the Christiania Foundation that was set up as an representative body and legal entity for Christiania. The agreement includes low-interest rate loans, the outright mortgaged purchase of certain properties, long-term lease on other historic buildings, and a lease on the park parts of Christiania, along with incentives that include significant collective loan forgiveness in return for Christiania’s successful upkeep, maintenance, and improvements in the public space and overall physical plant.

Individuals wanting to make improvements to their homes are responsible for one-third of the costs of improvement, for which they can receive a low-interest loan, while the remaining costs of home improvement are carried by the Area and the Common Meeting, further blending personal and community interests in relationship to otherwise private individual living spaces.

Robust Internal Economy

One afternoon when walking with one of the folks I interviewed, we ran into a fellow who stopped to ask about something related to his job, which was cleaning the public toilets. When we left my friend let me know that the bathroom cleaner was someone who ended up in Christiania and was semi-homeless for a period, until someone let him stay in one of the Areas. He then started voluntarily cleaning the public toilet in the Area, and figured out both that he was good at it, and that it was a useful contribution. He eventually ended up getting his own living space, and a job cleaning the central public toilets in one of the main Areas was organized for him.

Twenty-five percent of Christiania’s overall budget pays for wages, primarily for maintenance and improvement of the space and funding for school-related positions, with some portion related to the coordination, administrative, and supervisory work done through the Economy Office and the Building Office.[16] While overall budgeting is tight, and the financial burdens of the legalization deal are still becoming clear, Christiania has historically had the ability to provide some forms of sustainable and local work to some of its residents, allowing people to maintain sustained engagement.

Independent Enterprises

Christiania is home to a range of independent collective and private businesses, which pay a use-rent, as well as a lease fee and utilities for the spaces they use. Additionally, businesses are required to maintain open and transparent books to show that they are not laundering money or otherwise providing financial services to the hash trade. Businesses in Christiania have a regular meeting to collectively coordinate interactions with the Common Meeting and the Areas where they are located, and there is also a weekly meeting of people who work in the businesses. Christiania Bikes is a famous example of a successful independent enterprise that originally started as a blacksmith shop for residents who needed metalwork done while renovating their spaces. The shop’s designers created a cargo bike for transport in the car-free area of Christiania that later became hugely popular in bike-friendly European cities. Although Christiania Bikes’ growth has required moving their production facilities off-site, they continue to maintain a shop for sales, servicing, and repair in Christiania, and participate in the cultural and economic life of the community.

Cash Economy

No discussion of economic life in Christiania would be complete without considering the impacts of the hash trade. Some old-time Christianites tell stories that the hash trade began with hippy travelers returning from trips to India or Morocco in the ’70s with product to help fund their next trip. Although there are still some old-timers on Pusher Street, for the most part the trade is far more prosaic, having been dominated by biker gangs since at least the early ’80s—first by a local gang called the Bullshits, and these days by the Danish branch of the Hell’s Angels, whose inter-gang rivalries have occasionally devolved to armed attacks with rocket-propelled grenades.[17]

Where Christianites have largely defended on principle the right to sell cannabis, the difficult side effects of a biker gang dominated hash trade are acknowledged in public and private, while the community has been disciplined in rejecting the influence of profits generated by the hash trade. Nonetheless, a concentrated cash industry has a huge impact on the social fabric that, while most often is decried as negative, also includes possibilities for cash earnings by individuals stashing product, assembling pre-rolled joints, or other services adjacent to the industry, providing a perhaps complicated economic opportunity for some members of the community.

VIII – Shared Experiences

The business of ongoing community development often takes place in meetings, while the social networks and affinities that sustain collective decision-making are made elsewhere. Meetings, with the deliberation and decision-making that happens in them, are a consistent part of the consensus system. While meetings are open to every person’s participation, not every Christianite is always interested, or able, to participate, making the multiple opportunities to relate to each other and build relationships through time important to the sustainability of the system of consensus democracy at Christiania.

Parties, Social Gatherings, and Projects

In addition to meetings, events at artistic and cultural venues, and an active street life with opportunities for socializing, Christiania also hosts a range of formal and informal opportunities for connection and community building. In addition to public events, there are also a range of low-stakes opportunities for Christianites to gather in private and public settings to maintain their relationships. In a quick survey of a few editions of the Weekly Mirror over the years, I found a note about an upcoming table tennis tournament, an invitation to a work day promising fire, food, and music, a call for helpers to pull wagons for a children’s theatrical procession through Copenhagen, a solidarity party for young people, and a call to be part of an anti-Guantanamo action taking place during a NATO meeting in the city.

Collective Management of Common Space

When asked what motivated him to stay engaged, one of the Christianites I spoke with told me a parable about a pothole. While in regular society if there’s a pothole, neighbors will call the city to fix it, in Christiania the hole gets deeper until someone organizes to repair it, leading to deepened relationships and a shared sense of accomplishment. The first many decades of squatting and fixing residential living spaces, large buildings, and public spaces required high levels of participation in collective work; however, even as there are now fewer potholes, opportunities and incentives for Christianites to engage in management of public spaces remain. The Gardener Group plays a critical role in maintenance of the parks, lakes, walkways, and gardens. The Nightwatch is a group that informally keeps an eye on Pusher Street and the main cluster of venues and bars, available to quietly deescalate in a crisis. There are action days to perform group clean ups, to help neighbors move building materials, or other tasks. Additionally, the legalization agreement provides a collective financial incentive for successful management of the public space, with up to six million of an almost twenty million dollar purchase price, forgivable in return for collective management of bike paths, green spaces, and parkland, as well as other infrastructure.[18]

Shared Experiences of State Repression

Christianites have experienced intense periods of police enforcement and street conflict throughout the years. In campaigns to enforce regulatory rules and clamp down on the hash trade–during long periods that led to repeated street clashes with barricades and Molotov cocktails–police reprisals included intentionally tear-gassing children in a playground as well as a pattern of jailhouse beatings cited in a 1994 report by Amnesty International. In the 2000s, after a period of relative calm, a succession of Right Wing governments pushed a policy of privatization spearheaded by aggressive police actions, resulting in fighting in the streets, massive public campaigns, and concerts.[19] If Christiania is able to manage the terms of the legalization agreement the threat of eviction may recede; however, the hard-fought collective struggles for self-governance, collective ownership, and participatory democracy are ongoing.

Relationships in Time

Several of the Christiania residents I talked to freely offered being disappointed with former neighbors, partners, or collective members, over unfavorable results, minor betrayals, or misunderstandings. One talked about having left for a period of time after being disappointed with how the community handled a person accused of violence. Eventually returning, with his feelings mellowed and wounds licked, he joined a group that hosted conversations, skill shares, and presentations to support the better development of consensus practices. Christianites have had romances and children with each other, mental health episodes, committed to and drifted away from projects, shouted with, and probably at, each other. For those who persist, they can count on seeing their neighbors again tomorrow, and the next day, and the day after that.

Conclusion

Significant challenges loom on the horizon for Christiania, which had a Covid-subdued celebration of fifity years of occupation in September, 2021. Deferred mortgage payments are set to begin in 2023, the complexities of the legalization agreement are hard to understand, and future costs difficult to predict. Increased regulation and administrative requirements require professionalization and a bureaucracy that isn’t always accessible to some regular Christianites. Generational and cultural changes open the door to questions around what kind of common space future generations will want. Decreasing participation in meetings reinforces the risk of the processes and material of governance feeling out of reach for some Christianites.

I’ve had the opportunity to learn about other contemporary examples of participatory democracy in action since my time in Christiania, and I’ve been struck by both the similarities and the differences in various systems that have been invented or adapted to local circumstances. The Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico, for example, have been explicitly growing an indigenous system of participatory democracy and autonomy, beginning with devolving civilian governance to the juntas de buen gobierno.[20] To ensure that everyone gets to participate, the Zapatistas have created scaled areas of governance with feedback loops between community, municipal, and regional levels, similar to Kerala, India. In Kerala, constitutional reforms encouraging local systems of participatory democracy were enthusiastically embraced by a range of social forces and there are scaled areas of governance extending from village to regional councils, with feedback loops.[21] Cities in Brazil have embraced participatory budgeting, with the practical focus of direct democracy being around the development and allocation of common resources, a unifying shared interest that would be familiar to residents of Christiania.

There are also of course differences as communities striving for consensus and popular participation develop systems appropriate to local values, culture, and politics. In the Zapatista territories there is a system of rotational leadership that is envisioned to eventually allow everyone to become familiar with the requirements of government, whereas in Kerala an organization that had long advocated for more democratic participation trained facilitators to improve the participation of women and Dalits, or untouchables, who have beeen historically marginalized from political participation.

With the continued emergence of hard-fought experiments in horizontal and participatory systems of governance we will hopefully be able to learn by comparing and contrasting the large-scale system of participatory democracy in Christiania with how things work in Kerala, Porto Alegre, and the Zapatista terriorities, along with Rojava in Northeastern Syria, the indigenous communities of Bolivia, and other communities, projects, and places yet to emerge.

People in Christiania are aware of, and speak openly about their fears, along with their hopes, for the next generations of their community. Where legalization presents the community with material uncertainties, it also permanently establishes collective ownership, incentivizes continued investment and engagement in the shared commons, and supports ongoing experimentation in community-controlled development and participatory democracy. Hopefully, the legacies of shared struggle and experimentation will allow Christiania to continue to serve as a source for building understanding of consensus and participatory democratic practice.

Tauno Biltsted is a fiction and non-fiction writer, former cab driver, squatter, mediator and facilitator, and decent plumber and electrician. His first novel, The Anatomist’s Tale (Philadelphia, Laternfish Press, 2020), is a speculative historical fiction about pirates and a tropical commune of maroons.

Notes

[1] Rene Karpantschof, “Bargaining and Barricades – The Political Struggle over the Freetown Christiania 1971-2011”, in A Space for Urban Alternatives – Christiania 1971 – 2011, eds. Haakan Thorn, Cathrin Wasshede and Tomas Nilson. (Gidlunds Förlag, 2011), 39

[2] Author’s translation

[3] Jaap Draaisma & Patrice Riemens, “Financial Democracy and Participatory Governance in and for Christiania”, (Report written after residency at CRIR: October 3-31 (P), October 16-29 (J)), 2017

[4] Cathrin Wasshede, “Bøssehuset – Queer Perspective in Christiania”, in A Space for Urban Alternatives – Christiania 1971 – 2011, eds. Haakan Thorn, Cathrin Wasshede and Tomas Nilson, (Gidlunds Förlag, 2011), 184

[5] Tomas Nilson, “Weeds and Deeds – Images and Counter Images of Christiania and Drugs”, in A Space for Urban Alternatives – Christiania 1971 – 2011, eds. Haakan Thorn, Cathrin Wasshede and Tomas Nilson, (Gidlunds Förlag, 2011), 205

[6] Albert Bates, : Copenhagen’s Funky Jewel of Sustainability“, Resilience, (Dec 21, 2009), https://www.resilience.org/stories/2009-12-21/christiania-copenhagens-funky-jewel-sustainability/

[7] Thomas Seeley, Honeybee Democracy (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2010), Chapter 9

[8] Christiania Guide, 4th Edition, Written, photographed, and published by christianites, trans. Susanne Jacobi, 2005, https://www.christiania.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Guideeng2.pdf

[9] Ugespejlet. Wednesday, June 28th, 2006

[10] Asbjørn Nielsen, “Christiania – A Free City in the City of Copenhagen”, in Deciding for Ourselves, ed. Cindy Milstein, (AK Press, 2020), 143

[11] Ugespejlet, Wednesday, September 6th, 2006

[12] Resinga Malaghezi, TEDX Talk, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrrHWLSsmIc

[13] Maria Hellström Raimer, “The Hansen Family and Micro-physics of the everyday”, in A Space for Urban Alternatives – Christiania 1971 – 2011, eds. Haakan Thorn, Cathrin Wasshede and Tomas Nilson, (Gidlunds Förlag, 2011) , 132,

[14] Ugespejlet, November 15th, 2006

[15] https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-danish-anarchists-who-inspired-santacon-could-not-have-imagined-its-brohell-future#:~:text=The%20original%20inspiration%20for%20SantaCon,anarchist%20theater%20group%20in%20Denmark.

[16] Financial Democracy and Participatory Governance in and for Christiania, Jaap Draaisma & Patrice Riemens, in Residence at CRIR: October 3-31 (P), October 16-29 (J) 2017

[17] https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1996-04-18-9604180145-story.html

[18] Jaap Draaisma & Patrice Riemens, “Financial Democracy and Participatory Governance in and for Christiania”, (Report written after residency at CRIR: October 3-31 (P), October 16-29 (J)), 2017

[19] René Karpantschof, “Bargaining and Barricades – The Political Struggle over the Freetown Christiania 1971 – 2011”, in A Space for Urban Alternatives – Christiania 1971 – 2011, eds. Haakan Thorn, Cathrin Wasshede and Tomas Nilson, (Gidlunds Förlag, 2011), 38 – 67

[20] Amory Starr, María Elena Martínez-Torres & Peter Rosset, “Participatory Democracy in Action: Practices of the Zapatistas and the Movimento Sem Terra”, in Latin American Perspectives, January 2011, Vol. 38, No.1, pp 102-119

[21] Patrick Heller, “Democracy, Participatory Politics and Development: Some Comparative Lessons from Brazil, India, and South Africa”, in Polity, October 2012, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp 643-665