In Esmé Weijun Wang’s book of essays on the spectrum of conditions she calls The Collected Schizophrenias (Graywolf Press, 2019), she wonders at the evolutionary purpose of madness. Since so few of the traits of madness are on the list of generally desirable reproductive elements, why hasn’t it been selected out by now? How has it survived? The answer, she suggests, is that it is the shadow side of a great gift—that without the complex architectures, chemistries, and spirits that give us schizophrenia (seventy-six gene variations, to be exact), we may also lack our capacity for visionary thinking, inflammatory speeches, and collective dreams. In other words, the things that give rise to imagination can also drive us mad.

What, then, is the purpose of imagination? Many wield the idea like a flaming sword, as if we could slash through chains of oppression with the fire in our minds. All around us are calls to dream big, to think outside the box, to bravely envision the world we want as a necessary precursor to making it real. It’s cool to be a visionary right now, to embrace divergent thinking as a fundamental tool in our bag of tricks. Science fiction, fantasy, gaming, role-playing—all manner of accessing alternate worlds and realities help us crack the façade of common sense and status quo, revealing endless uncharted territories and potential beyond. Our imaginations can return to us the playfulness and joy our movements need, just as they help craft strategy and provide insight and reflection.

And yet imagination also serves another purpose, in terms of both evolution and our experiences as individuals. The role of imagination is not just to enhance our dreams, but to deliver us our nightmares. Ask any child who has clutched beneath the covers, fearful of what lurked under the bed or within the closet: our dark minds offer up with vivid detail all the things we do notwant to see in the world, as well. The preparatory imagination, the source of anxiety and fear, is also what prompts us to ready ourselves for attack, to plan for suboptimal outcomes, to respond to predators, disappointments, and bad surprises. It lets us ask, “What if…?” and steel ourselves for the worst. It is also this capacity for imagination that brings us our fascination with horror.

Judging by film and television, it seems that we are fixated on doom as a primary form of entertainment. Most viewers have witnessed the total destruction of Los Angeles, New York City, Tokyo, Chicago, San Francisco, several small planets and moons, and countless buildings, vehicles, and lives. The post-apocalyptic genre has become so commonplace that it feels at times like nonfiction, an inevitable menu of outcomes of late capitalism: imperial colonization by alien forces, zombie outbreaks, genetic modifications gone horribly awry, scarcity, drought, data blackout, superflu, climate change—what was once symbolic has become, in some cases, literal representations of very real fears.

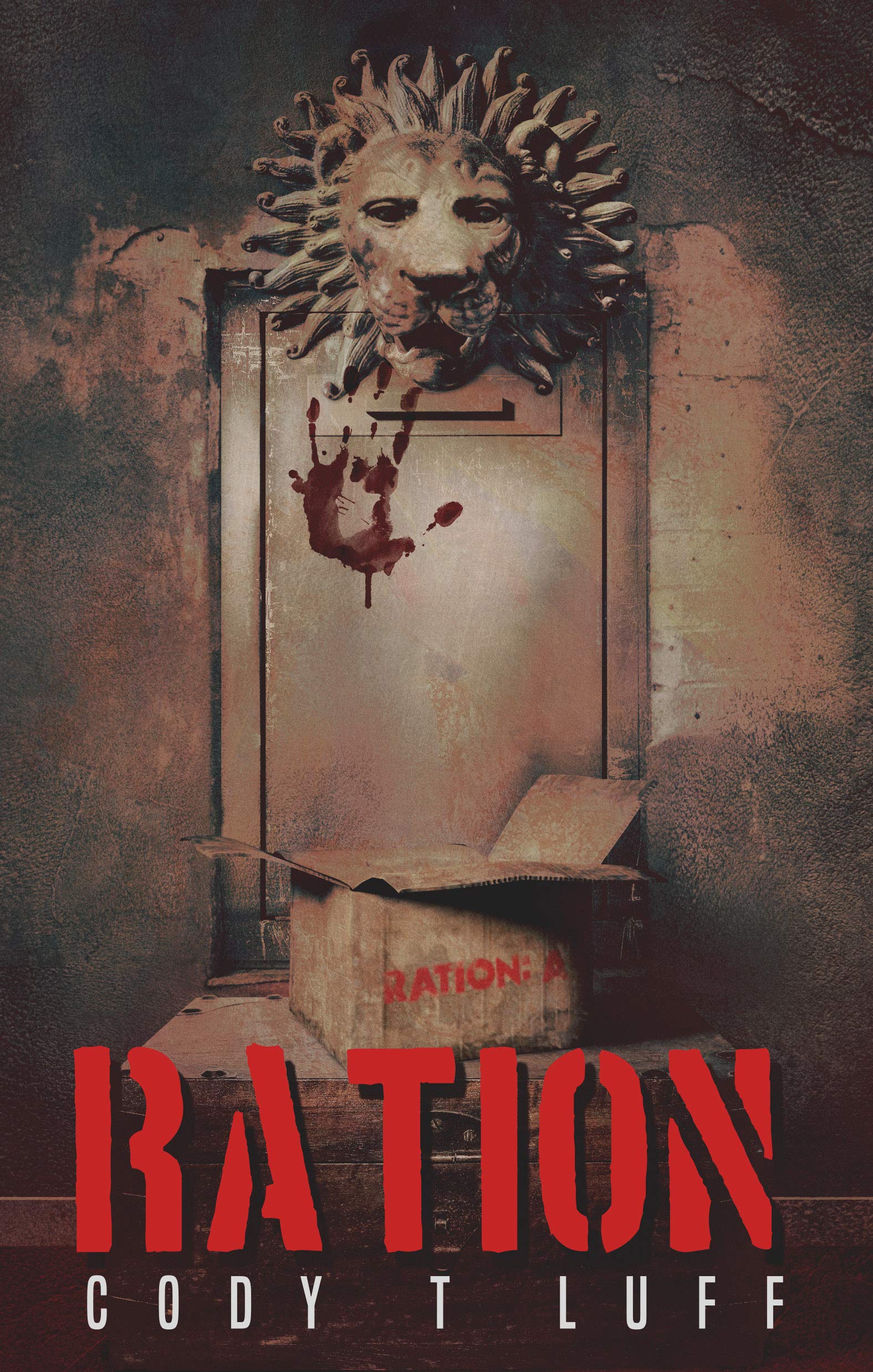

A new addition to this list of nightmare scenarios is Cody T Luff’s tremendous debut novel Ration (Apex Book Company, 2019), a deliciously weird and brutal set of what ifs that pushes past the ordinary bounds of the genre and drops the reader in a dark future no one was seeking to build. The opening chapters of the novel are so perfectly wrought and slowly revealed, I am reluctant to ruin the reader’s experience of discovery with a summary. Suffice it to say, Luff’s first what if is: What if the earth simply ran out of food? The second is: What if there were no men? With these two pieces on the board, the game begins.

Cynthia, a young girl trapped at the bottom of a rigid caste structure, is forced to make impossible choices between going hungry or causing the death of her peers in the grim farce of a boarding school where she lives. In this system, she confronts both the dogmatic and chaotic elements of oppression in the forms of two Women: Ms. Tuttle and Ms. Glennoc, both of whom are at the mercy of their own private hungers. Luff investigates the horror of scarcity with relentless and terrifying zeal, setting aside the mundane mechanics of nutrition for a much more interesting calculus of calories, a global economy based on the fundamental energy of survival. Within this market, what values would emerge? Endurance, self-discipline, and martyrdom rise to the surface in service of the ruling class. Beneath the explicit demands of the system are the hidden values that offer potential to the dispossessed: thievery, mob mentality, small mercies, and flexible loyalties serving shifting definitions of the commons. Within this set of social pressures, he constructs a thought experiment testing Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, inviting the reader to wonder what role love can play in such a world.

By removing gender and race and then starving the entire cast of characters, Luff also offers us a stripped-down analysis of power. Ration gives us a world where class and hierarchical structures become the only expressions of influence and domination, yet they retain all the same characteristics of aggression and cruelty. In this world, to be a Woman is to have education, access, choices; to be a girl is to be…well, livestock. How the two groups relate to one another and within themselves is, even under these extreme conditions, an uncomfortable reflection of many of our contemporary tendencies. Women’s bodies are commodified and pressured into unnatural shapes. Power is crafted and held through fear and the control of information and resources. Solidarity is meaningful and most effective when individuals are able to identify their own struggles within those of others—but also when there is a clear path forward. Without hope of change, without the capacity to create something other out of the ashes of what is, the project of liberation is essential and yet joyless, more akin to revenge than freedom. This is a world where people are hungry for more than food.

Luff’s writing is lush, vivid, often grotesque—it revels in its body metaphors and the tension between the sensual and the stark. At the same time, Rationreveals its secrets at a pace that is delightfully spare. Invisible yet thorough world-building gestures toward a rich and fully realized society and ecology, though like its protagonists, the reader has little opportunity to engage with them. Beyond the confines of the Apartments, where the girls reside, and the shattered, filthy remains of urban life, Luff has imagined a complete and horrifying future, offering us only those glimpses we need to understand the traps in which the characters find themselves. The author’s gaze upon the atrocities the world spits forth is unflinching, but rather than feeling sadistic or titillated, his descriptions have the remorseful clarity of one who witnesses a tragedy to pay respect to the victims.

Beyond the what ifs of the world, Luff also asks what ifs of convention. What if the hero weren’t really a hero at all? What if each set of eyes we peer through were more sordid than the last? What if we were forced to identify not with evil or superheroes but with the bland, occasional competence of the very ordinary? Cynthia is an exceptional heroine precisely because she is unremarkable. In her lack of heroism, she gives the reader an uncomfortably likely set of circumstances that is difficult not to relate to even as we agonize over her choices and limitations. By offering glimpses into the motives of the Women, by following their steps into the Wet Room for “processing” – unforgettable scenes that are sure to sear indelible marks on the collective subconscious of popular culture — we are left with a real sense of what it means to have no decent options in an unjust, broken world.

In his book Status Anxiety (Penguin, 2014), Alain de Botton said, “Tragedy inspires us to abandon ordinary life’s simplified perspective on failure and defeat, and renders us generous towards the foolishness and transgressions endemic to our nature.” He also suggests that the distinction between horror and tragedy is that horror contains no lessons to be drawn, only sensational violence, while tragedy serves to provoke reflection and change. Perhaps that is why Ration’s genre is so difficult to define—part sci-fi, part horror, part literary fiction—it represents that rarest of post-apocalyptic tales, one that uses the power of tragedy to encourage introspection. Luff provides no answers, no comfort, but he invites us to explore the edges of the what ifs where we would likely have been too timid to tread on our own. It is a powerful gift that he gives us. We are reminded that this, too, is a purpose of our darker imaginations: to allow us to project into a shadowed future and learn from its mistakes before they happen. The alternative is certainly madness.

Lara Messersmith-Glavin is a writer, educator, and performer based in Portland, Oregon. She serves on the board of directors of the Institute for Anarchist Studies, as well as on the editorial collective for Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. Her work has appeared in Across the Margin, Still Point Arts Quarterly, MaLa Literary Journal, Anchored in Deep Water: the Fisherpoets Anthology, Stoneboat Literary Journal, Gertrude Press Book Reviews, Selkie,the EMMA Talks collection Radiant Voices, and elsewhere. When she’s not in a classroom or working on a book, she can be found onstage with other Fisherpoets, exploring the woods with her child, or swinging kettlebells at the gym where she coaches. Check out her work at queenofpirates.net.