The decade we have left behind, the 2010s, was described by the British journalist Paul Mason as a time where “it’s kicking off everywhere.” What began with the Arab Spring protests in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and elsewhere, against the dictatorial regimes that ran those countries and in favor of democratic reforms, then followed with anti-austerity protests in Greece, Spain and Portugal, and in the form of movements like UK Uncut or the 15M in Madrid.

One historical re-telling might then say there was an ‘electoral turn,’ as these movements helped pave the way for the success of Left populist parties and candidates: from Podemos and Syriza to the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn. We can also speak of a wave of climate protests, from the youth-led school strikes to the movement for a Green New Deal. Most recently, there was another wave of Black Lives Matter protests, which mobilized over twenty-five million people across the United States, with many solidarity protests around the world.

However, the years since 2020 have seen a decline of the Left in America. With the election of Joe Biden, there seems to be a lull in more oppositional forms of protest. It’s within this context that I thought it important to return to one of the movements which kicked off the previous decade: Occupy Wall Street.

I recently sat down for an interview with Matt Peterson, a filmmaker, archivist, and political activist with a history across many radical spaces around New York City. He was active in the occupation movements at the New School for Social Research and Occupy Wall Street and is currently a member of the Woodbine collective in Ridgewood, Queens.

A decade after Zuccotti Park was occupied in New York’s Financial District, what does this experience tell us about our current horizons? From all we’ve seen, from Bernie Sanders’s second failed presidential campaign and the explosive George Floyd Uprising, what might the next spontaneous American social movement look like?

To engage with these questions through Occupy, we must first date it properly. While the ‘official’ occupation of the park was evicted in November 2011, the movement had an afterlife. In 2012, the momentum of Occupy would carry through into two events: the attempted May Day General Strike, and Hurricane Sandy’s arrival to the city on October 29th. Each of these affected how the movement was remembered, especially Sandy, which decisively transformed Occupy into a disaster relief platform.

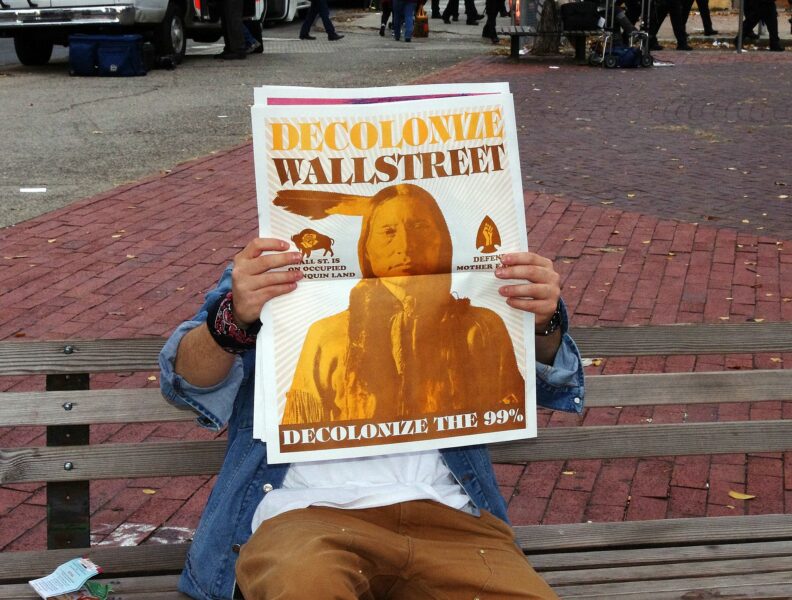

In effect, we can see these events as forming the beginning of a trajectory of a ‘long Occupy’— a horizon far longer and far broader than the initial occupation. We can draw a line from Zuccotti Park to a number of other organizational forms, including the two iterations of Black Lives Matter protests, the Standing Rock occupations in 2016,[1] as well as projects like Mutual Aid Disaster Relief (MADR) and other spontaneously organized response efforts during the pandemic.

It is also important to acknowledge the entrance of ‘Occupiers’ into mainstream politics, through the creation of progressive grassroots projects like the Fight for $15,[2] as well as the elections of activists like Sandy Nurse to New York’s City Council.[3] We could also point to global uprisings like the protests in Istanbul’s Taksim Square or the Brazilian fare protests. In all this we see a continuous thread: a generation developing skills and competencies to build autonomy.

While it began in Zuccotti Park, Occupy had many manifestations, from Seoul to London, and from Oakland to Washington DC. Our interview will focus on the New York Occupy and try to draw out the threads we take to be implicit in these experiences.

PART I: Where did Occupy come from? What was it responding to?

Amogh Sahu: We recently saw the tenth anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, so let’s take this time to reflect on Occupy, to think about what broader lens we can now view it from. Two guiding questions suggest themselves. The first stems from the way in which Occupy is co-opted in some official narratives; one that’s provided by the more mainstream, electoral left is that it was realized in the Bernie campaigns in 2016 and 2020. In other words, we should view these campaigns as a natural outgrowth of the sentiments expressed within the Occupy movement. Occupy raised the general issue of inequality, but without a story about what could be done about it. Then the Bernie campaign took the issue and provided a ‘solution’ to the problem raised by Occupy.

The other kind of pop narrative, which you hear on the non-electoral left, from insurrectionary anarchists, left communists, and the like, also sees it as a kind of steppingstone. From their reading, Occupy is more like a protean upsurge of the surplus population or some other excluded anti-state group, which represents a revival of anarchist and anti-electoral tendencies in the American left, and indeed in the left globally. This group is less likely to dismiss the form that Occupy actually took but it is more likely to think that Occupy was too ‘liberal’ for any insurrectionary/revolutionary tendencies to arise. So, partly I want to think about those, and to come up with a story of Occupy which tries to avoid the simplifications that both of those narratives impose.

Secondly, I think it is often missed how much Occupy was a New York City phenomenon. Of course, there were ‘Occupy!’ movements all over the world but Occupy Wall Street was very specifically enmeshed in the history of New York City politics. Other than the location, there was also the fact that the movement positioned itself against Wall Street, a New York-located financial institution, and that I think is something important and under-discussed, particularly with an eye to the later evolution of the left in New York City.

So, thinking through these two strands, on the one hand, Occupy as symbolic demonstration of broader tendencies of the left globally, and on the other hand, Occupy as this very rooted, New York-specific political movement. I know you were there on the ground for not just Occupy, but for several pre-Occupy movements in Europe—in Spain, Portugal, and England—and present for most of the time in Zuccotti and have stayed involved in New York movement building since. You’ve managed to see the long tail of Occupy, so how do you begin to approach this question of timeline?

Matt Peterson: Kristin Ross, in her book Communal Luxury, thinks more broadly about when the Paris Commune was, and she starts with some events in the years before 1871 that anticipated a sense that something like the Paris Commune might be coming. When I think about Occupy, I think about some of those early ruptural moments that were an indicator that something like it could happen, even if we didn’t really think it at the time. When I was a teenager I started to get involved in the anti-war movement after 9/11, protesting the early invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq during the Bush era. But during Bush’s second term there was a depression, because of the combination of just how large those movements were, and how simultaneously ineffective they were to really stop that administration’s ambitions in the Middle East.

For me, that confusion around activism started to change in New York in 2008, when there were these student occupations at the New School and NYU. The anti-war movement was really large, there were millions of people mobilized in cities around the country, even around the world, but the student movement was something different, it was small and molecular. That gave it a different sense of agency, a different sense that you yourself could influence it, that you could help create the narrative of the movement. The courage, bravery and experimentation, or recklessness, whatever adjective you want to use, of those early New School student occupations really set a different tone in New York. They had this slogan of “Occupy Everything,” and at the time that was seen as this adventurist and almost ridiculous demand. Their communiques had this very insurrectionary, anarchist tone which said, “We have no demands.” The occupation was about “the totality,” rather than any specific reforms around the campus or university.

Around that same time, in November of 2008, there were the raids in Tarnac, France, around the alleged authors of The Coming Insurrection. And December of 2008 is when there was a series of riots in Greece, after the killing of this young anarchist.[4] So, all of this was setting a tone for what was to come. And obviously, in the fall of 2008, there’s the Financial Crisis, the collapse of a number of banks based and headquartered in New York City but having reverberations around the world. So, this phase is an important dynamic leading up to Occupy Wall Street.

AS: You wanted to emphasize this new sense of agency and participation that you took to be core to the occupation. I have a couple of questions about this because this will turn out to be a running theme. My first question is, did you detect this new recklessness and sense of agency and excitement around the preceding movements, either the anti-war movement or the anti-globalization movement? Or was that something that appeared to you as a new feature of the occupations?

MP: It could have to do with my age, being a bit younger during those earlier movements, and gaining a bit more confidence or experience in the process, but the nature of those prior large-scale mobilizations meant that they were choreographed by these large coalitions. When they just ask you to show up with millions of other people, there’s not really the sense of what you yourself are contributing. You’re just another body that shows up to a mobilization, whereas the student movement, and broadly the occupation as a tactic, meant that there was more opportunity for you or a smaller collective to have some determining role within it. That shift was decisive in who participated and how people participated, and what the consciousness was around something like participation.

But why I wanted to mention Tarnac and the Greek riots was that around that time the Financial Crisis hits Southern Europe either faster, or in a more serious, devastating way than it did in the US. And there was a sense of solidarity with the so-called anti-austerity movements that had been happening in these southern ‘PIGS’ countries: Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain. Those movements also had more of an anarchic, social movement, extra-parliamentary context to them, which was an important influence for this pre-Occupy moment. I happened to be visiting Spain, Portugal, England, and Germany in that spring and summer of 2011, when those anticipatory movements were taking place: 15M, and these large encampments in Madrid, Barcelona, and Lisbon. These movements were basically the same as what Occupy would become, with large general assemblies occupying public space, people spontaneously forming working groups, all sharing a hostile orientation to the governance of austerity, and both the broader causes and responses to the Financial Crisis.

The other movement anticipating Occupy Wall Street is the Arab Spring, which also involved urban plaza occupations led by young, student-aged people, college-educated, who felt like they didn’t have a future, that there weren’t jobs available for them, and they were now facing increasing debt in a failing economy.

All of these people were breaking out of political parties, unions, or elections as a form or basis of organizing. This was something expressed globally, throughout the Arab world and Southern Europe, on both sides of the Mediterranean in response to this Financial Crisis. So that consciousness, that global solidarity with a more anarchic shift, and the move away from the large-scale mobilizations of the anti-war and anti-globalization movements.

AS: I have another question about the anti-globalization movement. There’s a general tendency to draw a connection between the anarchist elements of the anti-globalization movement, Greenpeace protests and environmental protests, deep green movements in the ’90s, and anarchist tendencies going back to the ’70s and ’80s to Occupy. And there’s some thought that there was some direct line from anarchist movements of the past to Occupy. To what extent do you think those kinds of parallels are helpful? And to what extent do you think that the analysis of an event like Occupy needs to be more historically specific?

MP: The movements I was mentioning were more of an influence. 2008 and 2009 aren’t that far back; they’re much closer in time to Occupy and the pre-Occupy movements. The events in the Arab world and Southern Europe are happening basically simultaneously, so it’s less of a stretch to mention those as immediate reference points and influences. Maybe historians would like there to be some American anarchic thread to trace from the ’70s to 2011. I wouldn’t say that isn’t there, but I’m skeptical. The direct lineage between those things is far more precarious and vulnerable than we would like to set out, as some genealogy or trajectory between those things.

What was interesting about Occupy was precisely that it was breaking with the forms of politics that existed at the time. There are three or four groups that maybe are worth mentioning. One of which would be the sectarian groupuscules, like the Trotskyist/Leninist/Maoist/Stalinist tiny groups, with all their initials and acronyms and newspapers, which were marginal and obscure. And I would include the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) within that, as being some sort of soft Trotskyist group. At the time, they were not much different than the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) or the Worker’s World. They were just one of another of these letter groups, which had very little social base, very little interest or momentum or membership rolls at all. So, that’s one strand.

AS: Subjectively, the way you encountered all of these “letter” groups was the same. You’d go to an action and then either a young volunteer or an old hand gives you a newspaper and gives you a clipboard with a mailing list. It’s the same.

MP: Yeah, maybe they have their banner at a demonstration or some book fair. They have a table, or their seven or ten members show up to a demonstration all wearing the same t-shirt or hat, which means that they’re part of this or that. There were maybe ten groups like that “active” in New York City, and the DSA was just one of them. It wasn’t much different than the others, really, though obviously some are more conspiratorial or harsh. At the time, people felt like the DSA was a bit more liberal, social democratic, fairly soft compared to something like Worker’s World or the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL), but that they were all basically in the same camp, so to speak.

Another strand of New York City politics in the moment of Occupy would be these community-based organizations (CBOs), these non-profit groups, issue-based groups. If the sectarian groups are very ideological or dogmatic in how they speak and who they reference, the non-profits and CBO groups are issue-based. They’re interested in housing or police reform, or immigrant justice, but they present themselves as professional, realistic, and legitimate. They have policy proposals or programs. They have some relationship to trying to lobby for legislative change, but also have the pretence that they have community, neighborhood, and grassroots support. They’re professionalized; they have ‘professional’ organizers and paid staff. They would be another wing of leftism: at a demonstration, they would also have t-shirts for their staff or members. This could blur into union membership, to the extent in which some local unions have activist or social movement relationships, they would be a third thing. And the fourth might be diffuse anarchist activists that aren’t part of any of those worlds but participate in movements and organize demonstrations.

Occupy was coming out of this latter group, this group of students and anarchists and activists who were really fed up by the sectarian groups, and who didn’t want to have this reformist, slow orientation of the community non-profit groups, and were not unionized workers. These were students, or people that had recently gotten out of school but were in a lot of student debt, or just people who couldn’t find a job. The economy shrunk after the Financial Crisis and as of 2011 it really hadn’t recovered.

The Occupy movement was really this rupture, breaking from electoral politics, from unions, from sectarian groups, and from the non-profits, to invent a new form, this outdoor occupation with general assemblies and working groups under the frame of direct action and mutual aid. The form was spontaneous, it wasn’t led by any particular organization. Actually, it didn’t have any affiliations with any organizations. So, it’s really a ruptural break from everything I mentioned, which is why it had this vitality. We realized just how many people are excluded or marginalized by all those political formations, and they needed some framework to express their disgust or contempt for the political. That’s broadly where this 99% thing comes in, this broad coalition led by these outsiders.

AS: You gave us an especially useful four-fold table of different New York left tendencies, sectarian groups, non-profits, union organizations, and these diffuse anarchist groups. Were you thinking of mutual aid and tenants’ unions as part of the fourth group, that diffuse social anarchist groupings, or were they not around before Occupy?

MP: There were always things like that. Mutual aid I would group in with a more anarchist ethic or approach to organizing. The tenants’ groups can straddle categories, because some of them are more in the non-profit realm in terms of housing advocacy, organizing, tenants’ rights, and they are professionalized with staff. Which I don’t mean to belittle, because some of that professionalization is helpful, where people have training and skills, and have studied and are aware of the laws and legislation.

But a movement like Occupy, that has this emancipatory liberatory potential or horizon, and a totalizing critique of what the economic system had become in the aftermath of the financial crisis, there was a sense that some of those community-based organizations or non-profits were not satisfactory vehicles for the kinds of liberation that people were hoping for. Now, after the fact, we can think to what extent that was naive or idealistic, but regardless, the situation was that people felt fucked over by the bailouts of the banks and felt incredibly precarious and vulnerable in their own economic situations. And seeing what was happening in Southern Europe, with large-scale social movements organized and mobilized to protest these things, there was this hope that there could be something analogous finally in the United States. That’s where Occupy comes from.

AS: And just to repeat a point that you’ve already gone over, that while you want to insist that Occupy came out of this diffuse anarchist sentiment, you seem to suggest that the best way to view it is as a historically specific reaction to some perception that other routes to social change were blocked off?

MP: Either blocked off or just insufficient. Either people couldn’t access those forms of organization, or even if they were able to, they weren’t sufficient vehicles to achieve the kind of liberation that people were hoping for. Those strands I laid out, we could also just call them the Left. If you think of something like the Left Forum, this conference is basically a collection of all of these individuals and organizations articulating their way of seeing the world. Everything in excess or outside of that we can think of as anarchism, this nascent activism which is where Occupy came from, that’s what its foundation was, everything separate or outside of the Left in that formal organized way in the schema I broke down.

Literally, the early planning meetings had to have this rupture, which is now part of Occupy’s historical mythology.[5]The coalitional politics of some of these groups had the pretence of representation of various communities, while this other more adventurist, vanguardist, or experimental form had to break with it, literally, in the form of those first general assemblies. It said, “We’re not going to listen to you, you have no credibility or legitimacy, you don’t represent us, you can’t do anything, you’re impotent, pathetic, backward, old fashioned,” et cetera. This was some of the youthful energy criticizing those movements that led to the vitality of Occupy Wall Street.

PART II: What was Occupy for? What was it Against?

AS: You mentioned that the focus of Occupy was in some sense economic, but you also characterized the criticism that was implicit in it as totalizing. Particularly with some of the texts produced around the Tiqqun grouping in France, there’s a real ambiguity about what the system and its boundaries are supposed to be, and I think that’s really captured by your use of the word ‘totalizing.’ Do you think it was important that the enemy was seen as this porous boundary between the state and the economy? The target was institutions that caused precarity without very much care to classify them as ‘political’ or ‘economic’? Maybe just say more about the totalizing character of the critique, and what the object of that was supposed to be.

MP: We could see Occupy as a populist movement, which might seem to contradict everything I was saying before, but what I mean is Occupy as a movement explicitly outside of the standard institutional political forms, and simultaneously able to be accessed by regular, normal people. More and more people feel themselves included in that institutional excess I was describing. We can think of that as having roots in Argentina in 2001, with their slogan of everything must go, or all of them must go, and then later in the Arab Spring you have this demand, “The people want the regime to fall.” In that context, we can think of the regime in two ways. On the one hand, the regime is literally identified with certain individuals, or certain familial forms of governance. In a broader sense, though, the regime was also identified with the global system, and in both cases this identification came without a story about what would replace the ‘regime.’

In the Occupy context, you have this slogan that became very successful, the 99% versus the 1%, but who and what the 1% is, is up for contestation. The ruling class is not literally the Senate, and it’s not just CEOs. It is something more like a Foucauldian regime of power, and that can include not just individual people or a governing family, but certain gestures, affects, norms or certain social forms. So, this neo-New Left sensibility is simultaneously criticizing Wall Street in a literal sense, but also the broader social or relational fabric.

The economy is broadly a catalyst, but it’s three years after the crisis hits, it’s not exactly some immediate response. We have to remember that there’s this big enthusiasm in the fall of 2008 for Barack Obama and his presidential campaign, and everything it meant. We have this new, young, charming, charismatic Black man, making this historic move to defeat not just the Clintons, but also to take over after this legacy of the Bush regime that we tried and failed to contest with the anti-war movement. You had this wave of Obama excitement, but he’s inheriting a financial crisis, so all of the enthusiasm within the electoral sphere becomes exhausted because we realize he’s not able to confront the banks, he’s not able to institute Universal Healthcare, he’s not able to close Guantanamo Bay, or really end the War on Terror in any meaningful way. That’s also a catalyst for the Occupy movement, these young people that had been inspired by Obama, and with him the belief that we can resolve the contradictions of society electorally. Three years later people start to say, “Okay, we can’t.” That this was not a satisfactory resolution of everything we’re feeling. Then people come outside, they say we’re going to go out in public space and meet and see each other, outside of these organized institutional forms of the left, and figure out what the hell can happen in a space like this. That’s really what the Occupy movement was.

AS: So, one way to think about this shifting reference of the enemy is that there’s some sentiment of like: We’ll wait and see. We’ll figure it out as opposition arises in different concrete, socio-political contexts. In the UK, it can be the London establishment. In the United States of America, it can be the Obama administration plus Wall Street, and so on and so forth. It’s less important to come up with some general abstract definition of who the enemy is. It seems like it’s more interesting to see that as a fluid, practical thing that concretizes in different contexts of activism.

MP: There’s some broad sensation that people just have to go out into the streets, and they will stay out in the streets until something happens, until there’s some change. And it’s almost like: We’ll wait. In a way you start to anticipate this framework of the strike, a people’s strike, or a general strike, which later becomes this horizon of organizing in the spring of 2012.

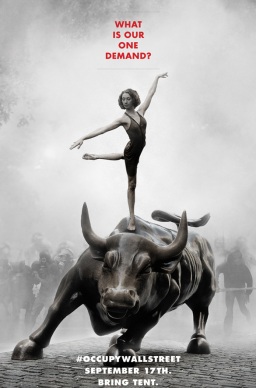

In that spring and summer in 2011 in the European anti-austerity movements you had large-scale, traditional general strikes in places like Greece and Spain and Portugal and Italy, where the public sector and unionized workforces have alliances or coalitions with popular social movements and can call for these general strikes together. We don’t really have that, the working class isn’t really composed that way in the United States, so something like a national general strike has never really happened in that traditional sense here. It’s inconceivable in many ways in the United States, but the Occupy movement was almost like this invocation of a strike. Even in the plaza occupations around the country, people have to go into the street and that itself is a form of strike, occupying public space indefinitely until something happens. That first month, in September, there’s this debate or question within the movement, what is our one demand? Demand of who and demand of what is unclear, but similarly a general strike is unclear too. What really is the demand of the general strike? It’s unclear, also. We celebrated it as some beautiful mythology, and Benjamin talks about this,[6] but it’s also unclear what’s supposed to happen. What are the steps between the strike and revolution? Occupy in its own naive way was embodying all of this.

AS: You mentioned the word populist. There’s obviously a lot of literature on what that word is supposed to mean, but central to at least one strand of populist thinking is the illegitimacy of traditional modes of political representation. There’s some kind of thought that existing political institutions, both formal electoral ones like the Senate, Congress, and informal ones like political institutions on the left (a number of the ones we’ve mentioned in this conversation)—there’s some thought that these have ossified, they’re bureaucratic, they feed into the existing system, they’re not zones of free political practice, and what we need is some other, in this case, spontaneous form, which arises out of excluded groups and is genuinely representative and democratic. That is a political lens through which to understand Occupy, right? The idea of democracy and the idea of expressing the will of the people is central there. And this certainly makes sense of stuff like the General Assembly. I was wondering if you could comment a little bit more on that element.

MP: Part of that is generational, where you have youth movements throughout history that don’t feel represented by the institutional forms that presently exist. That’s what you have with the New Left, where youth don’t want to join the Communist Party, or don’t want to join a union. There’re questions that they have that aren’t able to be answered by those forms. There’s an avant-garde, creative impulse to think of, imagine, and create a new form that can answer the questions that they want to be asked, and Occupy is just a version of that in this transitional moment, growing out of the 90s and 2000s.

One way of looking at history is to think about these moments, when certain organized forms are able to take the advances from this youthful avant-garde and try to institutionalize or legitimize them. You could later think of the DSA or the Bernie campaign as in some way picking up on the slogans, the frameworks, the political imaginaries, and horizons that came up spontaneously within the Occupy movement. Some leftists will think they were given legitimate form in these organized electoral or policy campaigns. A more anarchist line might be something like: No, then they become watered down, or all of the imagination gets sucked out of them, and they get funnelled back into the system. There’s that dialectic that plays out within social movements and their aftermath. Part of that becomes narrative, who gets to tell the story of Occupy, who gets to explain what it was, what it was for, who the actors were, what was important about it, what its innovations were? All of that becomes part of the media apparatus, and the extent to which a left-liberal intelligentsia controls those forms, they’re then able to narrate the movement, to give it sense or meaning through those lenses.

As you alluded to earlier, one example is the idea that Bernie’s campaign gave meaning or focus or purpose to the Occupy movement. Not that I have any major critiques of Bernie, but it was never hoped for by most people in the Occupy movement that that’s where it would lead to.

AS: Another thing that’s coming out of your responses is that trying to put a specific label on the strategy of the movement over and above its experimental, oppositional character is itself tricky. One frame one can have is very much this David Graeber frame, which is to think of the Occupy movement as a radical democratic movement, which is a distinctively prefigurative form of direct democracy, where the focus was explicitly on political questions. But another framing, which is more economic, is provided by the Endnotes collective. This is the framing of Occupy as the surplus population fighting back against the system that threw them aside. So, thinking of Occupy as a commune-like structure where people directly provide for each other’s needs in these working groups with food parcels and so on, that is also a more economic framing of the importance of Occupy. And it seems to me that both frames are partly right, partly wrong.

MP: I don’t see a big opposition between the two of them, myself. I think they can be synthesized. Part of the idea of the surplus population is, even if it’s coming out of an economic lens, is that any kind of a resolution of that condition is political, because they’re unemployed or unemployable, so it has to be up to the state to mediate any kind of resolution. It can’t stay in the private, economic realm. If the condition of COVID was one of unemployment, and still needing access to healthcare and food and money, all of those demands were addressed to the state. It’s the state that is supposed to give us unemployment benefits, it’s supposed to give us stimulus payments, it’s supposed to provide us healthcare, it’s supposed to get rid of our debt. The surplus population framework synthesizes the struggle around these economic contradictions as becoming political in its aims.

The question now is whether the state is able to mediate that difference, or that lack, or to what extent people on their own will have to self-organize to mediate that. The mutual aid framework comes up because the state is unable or unwilling to do something. These last years since COVID in many ways reminds me of the Occupy movement. The proliferation of mutual aid networks forming and spreading throughout the country has a clear resonance in the Occupy movement. But when we’re asking for mediation or resolution from the state, all of that is political, even if it’s about economic questions.

Part III: What were the Limits of Occupation as a Tactic?

AS: So, let me ask you about this creativity and feeling of agency in Occupy. How exactly does that manifest itself initially?

MP: In the summer of 2011 there’s this AdBusters call for people to occupy Wall Street, for people to come together, basically as a mobilization. In August there started to be these general assemblies in New York, and initially they are called in coalition with some sectarian groups, and some of these non-profit organizations, but then it splits. That’s where people like David Graeber, a Greek performance artist named Georgia Sagri, and other people from 16 Beaver, this political art space in the Financial District, literally break away from this meeting and organize their own autonomous general assembly, where everyone can talk and participate. Those start to happen weekly in Manhattan, in Tompkins Square Park and elsewhere, and people start to come and meet and talk and brainstorm about what kind of movement they would want, and how it would be organized.

There’s this deadline of September 17th, when the occupation itself was supposed to happen. There’re maybe six general assembly meetings prior to that, just these outdoor public meetings, but there’s a lot of interesting experimentation. And then the occupation happens, and that becomes this catalyst for people to come 24/7, and more and more people start pouring in because New York has this spectacular mediatized gaze on it, both nationally and globally. Even if the park itself is quite small, and the initial numbers were not very many, it starts to symbolize something, and then other cities and towns across the country and world start to mimic it. It has this mimetic character where people start to take it on and copy it and adapt it.

AS: Another theme I’m picking up on is the use of emotion and affect to characterize the momentum of the real movement. Using words like hope and enthusiasm and creativity, I’m interested in whether what held Occupy together was this mass affect, or this specific tactic of occupation. What was the glue for the movement, at least early on?

MP: One of those things leads to the other: the tactic of an occupation lends itself to being held together by affective binding. Because in all these forms, something like Twitter allows itself to be inhabited by a certain disposition, something like a formal bureaucratic sectarian organization lends itself to being inhabited by certain dispositions, or certain gestures or ways of thinking or communicating. In an occupation, which has this reproductive quality, people must come together with strangers and figure out how to make things happen, how to sleep next to each other, where to build tents, how to find food, how to cook, how to run general assemblies, how to experiment with calling for spontaneous direct actions. And then think about all those things simultaneously, and reflect on them, and form these working groups with strangers to experiment with doing things that many people had never done before. All those things lend themselves to being inhabited by certain kinds of people, or having certain kinds of emotional or affective experiences.

Even if a person might be a union bureaucrat in the MTA, to have them participating, sitting in a circle on the ground in a park in the Financial District pushes them into a different modality of relation, where they must communicate with a seventeen-year-old kid with pink hair. And then a senior citizen, or a veteran of the Iraq war, or a homeless person, or someone experiencing a mental health crisis, with someone who just graduated from NYU with a hundred thousand dollars of debt. All these people, you have society flung into a park, and they must figure out how to communicate and make decisions and make things happen. That lends itself to a more emotive or an affective lens, whereas in a DSA chapter meeting that is following Robert’s Rules, certain people will thrive, but that’s different than being in a park where someone’s handing you a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. The bodily experience of it just evokes different emotional responses. That tactic of a plaza occupation was therefore not that ideological or dogmatic, or not that coherent politically, because it was this practice of a public strike, but in various messy, complicated, confusing ways. But that gave it so much of its charisma or vitality or energy.

AS: However, there are the criticisms that have been made of it. One, more observation than criticism, is that some of the affective, more spectacular elements of the tactic of occupation and its messiness lent themselves to becoming mediatized in some fashion. I don’t want to claim that experimentation in public space is essentially a media spectacle, but I think it seems to me to be a statement of fact that contingently, there was something about the way that Occupy developed and the context in which it developed, which made at least some elements of it a useful media spectacle.

MP: This is a tension you also have in the sixties between the Old Left and the New Left. If you want participation, if you want numbers, it’s this political contradiction of, well maybe the Old Left groups were right, or were smarter, they had studied, and read all the right things, were students of history, and understood how the economy worked, but it was just boring and drab, and wasn’t going to appeal, either to new younger workers, or to a new youth counter-cultural movement. Similarly, maybe if you went to the Left Forum in 2010 or 2011, maybe the people there were right, maybe they did have a more sophisticated analysis of bourgeois politics, of imperialism, of the exploitation inherent within American financialized neoliberal capitalism, et cetera. But the ways in which they presented themselves, and the figureheads and the organizational forms they used, were just never going to involve the numbers of people they would need to become a potent movement. So, being right or wrong may or may not matter historically, because people will just not join your organization if it feels stagnant or stale. Something like Occupy had a charisma to it that enabled it to attract way more people, and a lot more experimentation.

AS: The criticism is that the seductiveness and the participation became ends in themselves in the light of the media spectacle, without really leading anywhere. So I think it’s definitely right to say that the mediatization was an inevitable consequence of the simple fact of enthusiasm and excitement. It would be too glib to write off Occupy itself as a guerrilla marketing event. But I think there is a genuine element at some point, perhaps this represents decay, or perhaps this is an internal decline of the movement, when you see stuff like enacting participation, coming to take on a purposeless self-indulgent character.

MP: The Occupy movement was growing from September to October to November, both the amount of occupations and encampments in different cities, but also the participation in those cities was growing. Then in October and November you start to see a series of evictions by local police departments, and there was evidence of coordination between various mayors and governors around those eviction attempts, because they start to happen on the same days or weekends. Most of the major flagship cities were forcibly evicted from their encampments and were prevented from returning to them. They’re physically cleared through force, there’s lots of arrests, there’s police brutality, and then the encampments themselves are barricaded off. And then other public spaces become barricaded off in a number of cities, like New York and elsewhere, so the encampment tactic was physically prevented by the police and the state, and then the movement has to figure out how to adapt. It’s not fair to say that it just fizzled out because of its spectacular mediatized decadent indulgence: it was physically enforced, evicted in New York and many other places.

Once you remove that foundational experience of the public plaza occupation, it struggled to find its footing in a new paradigm. The most important part of it was the occupation, having that physical space, it was almost territorial or a land question, even on a small, micro scale. Once that territory was removed by the police, or the city, or the state, the movement found difficulty in pivoting. A lot of the assemblies and working groups continued to function but lost that foundational practice or experience which really bound things together.

That’s when it started to shift towards the strike, the general strike on the West Coast. You have these port strikes in Oakland, up and down the entire West Coast, and then in New York and nationally people started thinking towards May 1st, 2012, as this national general strike. In the absence of the occupation, things start pivoting towards that, which whether or not a general strike happened on May 1st, 2012, it was an interesting pedagogical experience for people, both the experience of the occupation, the experience of police and political oppression, and then this horizon of more traditional organizing or mobilizing, to try to reach and communicate with different segments of society, to try to engage them in something like a general strike. So, who can call for a general strike? What does a general strike mean? What does it look like on the day of? And this is all in the absence of something like the AFL-CIO itself calling for it, or any unions themselves calling for it. So, what does a popular, populist general strike look like?

AS: About the occupation, occupations are disruptive. The traditional way of thinking about disruptive actions is that they aim to occupy space where important functions of social reproduction happen, and they aim to put a gum in the works, to stop the institution. This is a conception of an occupation which puts it in close conversation with traditional strike organizing, but occupation of public space, particularly a park is not quite the same, because you’re not occupying a police station, you’re not barricading a bridge, so the focus of the occupation is not to, at least not primarily, to hold social reproduction. It’s rather to have a space to gather.

MP: To occupy public space is almost to create a base of operations. On the one hand, it’s a space to gather, but in the process of gathering it takes on this aspect of reproduction because the people gathered and sleeping there have direct material needs. They need food and drink, they need a place to piss, they need shelter from the elements, so you need to build this place up to have more resources, and there are things like free clothes, and cigarettes, and a medical tent. There was an entire world in Zuccotti Park, there were libraries, educational forums and lectures and presentations, and that was happening throughout the country.

Because it’s in public space, it’s also this populist contestation of space. It’s not exactly an occupation, because public space is ‘our’ space. There’s this populist dynamic, for people to just assemble and gather in public space as a political action or gesture, to reclaim space from neoliberal, privatized, metropolitan governance that wants to send people home, push people away from each other.

Also, it functioned as a base of operations meant that there were daily, multiple marches and disruptive actions that emanated from this space that went to Wall Street. For the entirety of the movement Wall Street was barricaded, that bull on Broadway and Wall Street was barricaded.[7] It was disruptive because there were daily marches around the New York Stock Exchange and all of these financial institutions. There were protests multiple times a day. Even if the park itself wasn’t disrupting anything because it was just a public park, it did function as a base.

There was this limitation that other friends and I were focused on in October, November, which was the move towards indoor private property. We felt like that was one of the contradictions of the movement, where it was unable to make that leap to indoor private space and contest those private property relations. We wanted to push it in that direction, but we were a small minority, and that was seen as outside of the bounds of what the movement was interested in. Maybe that addresses some of your questions.

But it’s not like it was in the woods and people were just gathering there. It was on Broadway: it was directly across the street from the Ground Zero site, the site where the World Trade Center had formerly been and was still at that point more of a construction site, so it had that symbolic value. It was just blocks away from Wall Street, and all of these financial institutions that saw marches on a daily basis.

One of the things that was different from some of the Southern European cities is they have these traditional large public plazas where people gather, they have this more popular dynamic, whereas Zuccotti Park is not a very trafficked public space. One of the moves later in the winter and spring was to move to Union Square, which is much more like a traditional plaza, where lots of people are going and hanging out and socializing. There the movement could interact with a more traditional public space, to try to take on more resonance or participation to generalize throughout the city itself, as opposed to being a distinctly activist practice that would only appeal to fringe freaks.

PART IV: How did Occupy ‘end’?

AS: In terms of the transition into 2012, you mentioned that things were already dying down in November as evictions were taking place. What happened during the transition from November to January 2012?

MP: There was already some frustration with the encampments because they were complicated and messy and dysfunctional. There are all these people with these crazy ideas, some of which don’t fit into your view of what politics should be, and it’s awkward and difficult to deal with hippies and liberals and student activists and the “End the Fed” conspiracy people and libertarians all at the same time! And, spatially, being in a public park in the fall means that it’s getting colder, and it’s then becoming harder to feel you can make any progress. We wanted to defend the park, and we were disappointed that it was evicted, but there was also a relief. Afterward people still felt taken by this movement, and were participating in it on a daily basis, whether or not they were sleeping at the park. We wanted to think of Occupy as not just what was happening inside Zuccotti Park, but all these other direct actions and projects.

Once the park was evicted there was this sense that it could be a good thing. The idea became to pivot to all these other things that we felt were or should be part of the Occupy movement but were not part of Zuccotti Park. Maybe even that Zuccotti Park was something of an albatross, that the energy involved in maintaining and defending the park prevented us from having discussions about broader issues, like confronting the banks, or confronting the police, or confronting private property, or confronting debt, all these questions that had nothing to do with the park itself.

At that time, there was also this transition towards different borough and neighborhood assemblies. There was an Occupy Brooklyn general assembly and an Occupy the Bronx general assembly, which turned into Take Back the Bronx. There were calls for neighborhood-specific general assemblies in places like Sunset Park or Williamsburg or Bushwick, either outdoors, or indoors at churches and other spaces. This was an attempt to engage people in the city that maybe weren’t or wouldn’t be going to Zuccotti Park. This especially included people from certain working-class neighborhoods that seemed absent in Zuccotti Park.

That fall there’s a push towards emphasizing these neighborhood and borough-wide assemblies, but there’s a question about where the momentum for this push is going to come from. People begin asking, “What do we do if we’re not reproducing encampments?” And if there’s this reluctance or hesitancy to do indoor occupations, how do people enact the core idea of Occupy: reproducing themselves in a space together to oppose the existing structures of power? And that’s when there is this push towards the general strike. That November Oakland did their general strike, where they shut down the Port of Oakland, partially in response to the eviction of their encampment there. And later in December there was a port shutdown throughout the West Coast, so there was already this idea of wildcat strikes with traditional unionized workers in a coalition led by the Occupy movement. So, we were just like, “Okay, we should have a national general strike,” and May 1st became the day because of the historical resonance with Chicago’s Haymarket riots.

As the fall turns into winter there’s this push towards thinking about calling for a general strike. And there’s lots of meetings, all of these neighborhood assemblies, working groups, borough assemblies, the Occupy assembly, and people are traveling to different cities, encampments, and assemblies. All of us are trying to work on a national coordination for a May 1st general strike, so that’s really what takes over the movement. For the rest of the winter and spring everything really is oriented to that, because people have given up on how we could maintain an encampment, both because the police are preventing it and also, it’s just cold, like, “Do we really want to sit outside in the freezing cold just to have an outdoor encampment?”

AS: Would it be fair to describe this general story as a diffusion of the initial Occupy encampment in Zuccotti Park into all of these other encampments and an attempt to explore strategies that extended beyond the initial occupation of public space?

MP: There were indoor occupation attempts throughout that first fall and winter that some comrades and I were involved in, but we were marginalized by the broader movement. After Zuccotti is evicted, everything’s still happening under the framework of the “Occupy movement,” and people are still identifying everything as Occupy, but without the plaza occupation being the foundation. But that diffusion was a good experience for political education, because people are going into different neighborhoods to talk about the Occupy movement, what it is and means, and how it might relate to certain neighborhoods, to different sectors of work. Police brutality also becomes more of a focal point of the Occupy movement, because that’s what it was directly confronting by that point. So, Occupy is starting to talk about new and different things.

Obviously, the general strike represents Occupy trying to talk about labor and the economy in a fairly traditional, but provocative way. The general strike is this very old-fashioned idea from the labor movement, but it’s brought by the Occupy movement into this new, post-modern, twenty-first century, multitudinous context. That was an intervention that I was excited about, which was met by a lot of cynicism or skepticism from some of the old left sectarian groups who were like, “You guys are idiots. You don’t know what you’re talking about,” or “That’s not what a general strike is.” So, to revive this dead or archaic form into a 2012 context was a really inspiring intervention that we tried to make, whether or not it was successful. Something like a general strike is still on the horizon, getting masses of people to participate in a coordinated act of refusal. That’s what Occupy was trying to do, and that’s still the question now.

Notes

[1] The protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline occured between April 2016 to February 2017. Some of the most prominent actions happened at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, across the border between North and South Dakota, and the protests are often referred to simply by using the name ‘Standing Rock.’

[2] A progressive grassroots movement in the US, aiming to create a nationwide $15 minimum wage. It began in 2012 and is still ongoing.

[3] Sandy Nurse is an insurgent candidate for New York City Council, who won the 37th district election in 2021. They defeated incumbent Darma Diaz in the Democratic primary.

[4] Peterson is referring to Alexandros Grigoropolous, the Greek student who was shot by a police officer in December 2008.

[5] We can trace this story in Yates McKee’s Strike Art (Verso, 2016).

[6] The specific reference here is to Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” in Selected Writings Volume 1 (Harvard University Press, 1999). We can also mention Sorel’s Reflections on Violence (Cambridge University Press, 1999), which was also a point of reference at the time (according to Peterson).

[7] There is a statue of a bull in the Financial District of New York City. It came to be seen as a symbol of financial optimism, drawing on the notion in finance of a ‘bull’ as an optimistic speculator.

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter (1996). “Critique of Violence [1921],” in Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (eds.), Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 1: 1913–1926. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McKee, Y. (2016). Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition. Verso Books.

Ross, K. (2016). Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. Verso Books.

Sorel, Georges (1999 [1908]). Reflections on Violence (trans. T. E. Hulme, ed. Jeremy Jennings). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.