“When we look back at the 60’s, one of our greatest shortcomings was, we were emulating the very people we were fighting against, our morals, values and ethics were the morals and values of the society we were struggling to change.”

– Imam Jamil El-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown)

It was early April, 1998, eleven days before my twenty-first birthday, when I heard these words from the former Chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). H. Rap Brown struck fear within the psyche of America’s ruling class in 1967 with his famous declaration, “If America doesn’t come around, we’ll Burn it Down to the Ground.”[1] I was at a testimonial dinner for Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) in my capacity as student body president at Howard University (HU) my junior year.[2]

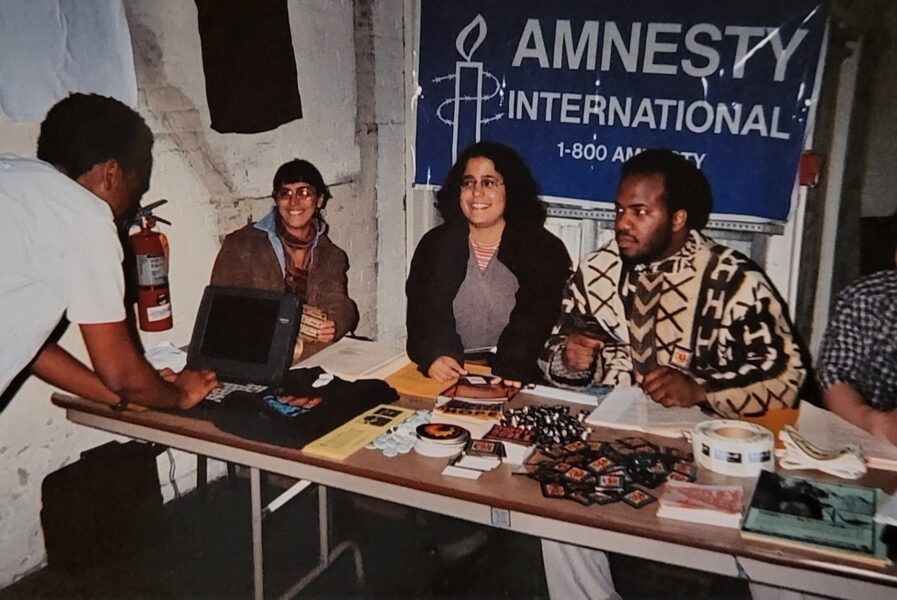

After nearly four years of consistent student and community-based activism, I graduated from Howard, and a year later, got a job as Amnesty International’s Mid-Atlantic membership program coordinator. My job was to oversee, service, and support the student-youth movement of Amnesty throughout the Mid-Atlantic states, numbering roughly 300 chapters in high schools and colleges. Within less than two years, I would come to intimately understand the words Imam Jamil spoke. By the summer of 2002, an anti-racist struggle had ensued within Mid-Atlantic Amnesty that would severely impact my life. My lived experience within that struggle serves as a primer for any anti-racist, especially a Black person within the United States, aspiring to work on the staff of a non-profit organization.

The Mid-Atlantic team was a tight knit staff in a very robust environment within the DC Office of Amnesty. The office, situated a few blocks from Capitol Hill, housed most of the national organizational programs including the legislative operation. Our team was one of five regional operations throughout the country charged with maintaining a cadre of human rights foot-soldiers. Being that the office was within earshot of Embassy Row (where most foreign embassies are located) our office was the primary focus for mobilizing Amnesty members to rapidly respond to human rights abuses across the globe, mostly through letter writing, lobbying, picket lines, and mass rallies.

My primary training consisted of me becoming grounded in the culture of the organization, its systems of operation along with those key Volunteer Leaders throughout the region I needed to be in relationship with. After two and a half months on the job, the most training I had received was how to effectively clean my file cabinet. I did my best to work with what I presumed to be my trainer’s style, but ultimately concluded what was taking place was deeper and far more profound.

I wrote a memo outlining concerns that my training had mainly taken place by osmosis with key aspects of the job being withheld from me; a departing intern informed me of new student group registrations coming in via email, the Administrator alerted me to a “Volunteer Leadership Notebook,” our IT staff member alerted me to a leadership database I could use, all of which was withheld from me. Most disturbing of all though was my trainer’s overall demeanor and disposition. Whenever I asked questions, they would either obfuscate by focusing on the low performance of past people in my position, or directly tell me on more than one occasion it was my job to listen to them and follow orders.

After receiving my memo, the directors met with me about my concerns and my trainer was relieved. For roughly a month, the deputy director became my primary supervisor and wanted to ensure I was deeply invested in what he considered the organization’s core work of focusing on human rights abuses abroad.

Amnesty was founded in 1961 as a global movement dedicated to freeing Prisoners of Conscience (POC’s) incarcerated by governments throughout the world. For decades, Amnesty had a global mandate that barred members from working on human rights abuses within their own country—the premise being that this policy protected human rights defenders from being persecuted or at worst extrajudicially killed. However, for the defenders within the United States, this policy ensured that privileged mostly white Amnesty members (the base of the organization) never had to seriously confront their own government. In essence, for many years, Amnesty’s global policy ensured that its members within the US never had to seriously confront domestic racism.

The Deputy’s vision for my forward trajectory would be challenged and seriously altered by the police murder of an unarmed Howard University alumnus-classmate of mine named Prince Carmen Jones by Prince George’s County Maryland Police on September 1st, 2000. Prince was trailed in an unmarked vehicle through three police jurisdictions before being murdered in Fairfax County, Virginia. His only crime was being a relatively privileged young Black male driving a black Jeep Cherokee provided to him by his parents. The killing sparked national outrage and weeks of regional protest both in Prince George’s and on the campus of Howard University.

It was during this time I began to not only experience my director’s leadership and truly understand her human rights ethos, but to ultimately understand more deeply her motivation for recruiting me to the team. A thirteen-plus year veteran of Amnesty’s staff, this person credited the late Black human rights champion Keith “Kamu” Jennings with grounding her in an anti-oppression framework for human rights advocacy and organizing.

As the Prince Jones Movement continued to build, we met daily to strategize and think through the best ways to respond. The director thoroughly knew the Amnesty landscape and she grounded me in the internal policies to support our Howard University student members on the ground. By the Summer of 2001, we hosted three human rights hearings with survivors of police brutality-torture within the county.

Nevertheless, my work with the director and our efforts in Prince George’s were not representative of the institutional culture within AIUSA. Behind closed doors, the Deputy quietly resisted our entry into the county telling me at one point to push that work to local organizations. Our work to diversify and combat racism was expanding within the region. The result was the internal intensification of the struggle against racism within the Mid-Atlantic regional office itself.

From a policy standpoint, Amnesty USA was committed to anti-oppression work and anti-racism. The guiding policy for the organization was known as the “Multicultural Development Organizational Plan,” which charged the movement with diversifying through an anti-oppression ethos. The basis for Amnesty’s ideological undergirding came mostly from the New Orleans based People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond.[3] Founded in 1980 within the home of the late Civil Rights pioneer Rev. C.T. Vivian, the People’s Institute is an organization dedicated to training organizers to struggle with a grounded understanding of racism as the major Achilles Heel to our forward progress both in the society and our movement. A few staff members had participated in the People’s Institute anti-racism training. Nevertheless, despite the organizational mandate, my lived experience as an Amnesty staff member encompassed consistent anti-Blackness, bigotry, xenophobia, Black male misandry, and ultimately racism itself, from staff, interns, and volunteers. Some of the most salient experiences were:

- A supposed “Red Flag” being raised against our Howard University student group stating it was against “white supremacy” on a flyer for an upcoming anti-death penalty forum. The deputy stated Amnesty had not issued such a directive. This became an internal struggle with the students not compromising on language.

- An intern became defensive when she saw a picture of Confederate General, Nathan Bedford Forrest, original founder of the KKK, on my wall in his Klan Uniform—an article I had cut out from a newspaper. She told me her granddaddy was in the Klan and they weren’t so bad but were defenders of Southern pride. This was the same intern that questioned me on why civil rights leadership were protesting the hanging of a young Black male in Mississippi. She stated the coroner ruled the hanging a suicide, so she didn’t understand the basis for the protest.

- One afternoon I remember asking an intern for a ticket to a fundraising event they were coordinating later that evening. The response to me was, “Can you hang by a rope until 5pm?”

- In preparation for a statewide meeting in Pennsylvania, I had both a phone call and email exchange with the state death penalty action coordinator who stated her refusal to utilize AI’s International Report calling for a new trial for Mumia Abu Jamal and for the death penalty not to be applied in his case. Her resistance was based on the high number of death row inmates in Pennsylvania and wanting to focus on the totality of the injustice. However, she was very up front in her opposition to Timothy McVeigh’s pending execution for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

- In preparation for a regional speaking tour for recently released General Jose Gallardo, from Mexico, an intern told me the General’s son Francisco was staying in a “bad” neighborhood. When I inquired as to what constitutes a good neighborhood, she told me one that is gentrified.

Amnesty’s multicultural plan was guided by a Multicultural Assessment Advisory Committee composed of a few board members and staff. The committee put out a call for any staff members that desired to attend a fully funded, weekend-long, anti-racism training to be held in Atlanta, Georgia in July 2001 sponsored by the People’s Institute. Only three staff members answered the call and they were all Black men, including myself. This training had a lifelong impact upon my organizing. The key principles I deeply internalized and utilize are:

- Organizing skills should be taught in tandem with an in-depth understanding of racism, militarism, politics, and history. Organizing skills alone are not enough to build the coalitions necessary for a broad-based movement for liberation.

- Racism equates to hatred; prejudice plus power. Power is defined as the legitimate access to the institutions sanctioned by the state.

- “Liberating the Gatekeeper”—a gatekeeper is one who is hired, trained, and ordained to represent an institution and its worldview inside an oppressed community without the community’s permission.

I remember the gatekeeper principle being very difficult to embrace. It was initially hard to internalize that as a Black male I could be a “gatekeeper” within an oppressed community. However, after some in-depth group discussion, I came to the conclusion that structurally all non-profit organizers function as gatekeepers for their institutions. “Liberating the Gatekeeper” is a revolutionary act where the non-profit organizer intentionally shifts their focus to helping build the power of those most directly impacted from a service-support position and not one based in authority that solely perpetuates the institution they work for.

With this newfound knowledge and inspiration from the People’s Institute coupled with my lived Amnesty experiences, I was inspired to organize such a training for Mid-Atlantic staff and volunteers. Upon receiving the director’s strong endorsement, I reached forward to my counterpart, an openly queer human rights organizer in the Southern Regional office. It was their vision to broaden the training to encompass the People’s Institute analysis with that of Project South within an anti-oppression framework. I agreed and took the lead in organizing the participants—while they put together the content and flow of the training.

I have two salient recollections leading up to the anti-oppression training. My first memory is overhearing colleagues right before a staff meeting where the deputy, recounting a past training, stated the definition given of racism in a sarcastic way. The organizer didn’t give a rebuttal, so I felt obliged to. The other memory involved the HU student group faculty advisor, an economics professor and longtime member of the Marxist-Stalinist Progressive Labor Party.

For the faculty advisor, smashing racism requires a multi-racial class war against the ruling class led by a vanguard workers party. The professor was very strident in organizing to physically attack fascist scum in the streets, so I initially found his criticism of the anti-racism training to be odd in character. He equated the upcoming training to folks spending the weekend gazing at their navel.

I believed that anti-oppression training could potentially begin a process of undoing the deep internalized oppression preventing too many Black folks from understanding that it is the system, not our so-called personal deficiencies, which causes the daily scourge of state-sanctioned violence perpetrated upon our lives.

I was also convinced that for the professor to fully endorse and partake in such a training, he would have to face the reality of how institutional racism and white supremacy benefits his own life.

The professor’s sole focus in being a faculty advisor was to build the ranks of his party. An aspect of his cadre recruitment strategy entailed penetrating groups like AIUSA to identify potential recruits by raising class contradictions and consciousness within the organization thereby solidifying deep political and personal relationships.

I witnessed the best example of this recruitment strategy in Fall, 2004 on the University of Maryland campus. This was at the height of the Iraq War with the US having invaded Fallujah for a second time killing hundreds of unarmed civilians. The professor presented an emergency resolution at the regional conference highlighting the atrocities in Fallujah as human rights violations pressing upon AIUSA to call for the immediate withdrawal of all U.S. and Coalition troops from Iraq. This resolution brought fierce opposition from all sides in the region including written opposition from the executive leadership. The resolution was voted down 44-25, however, the professor’s objective was not focused on winning the vote but exposing AIUSA to the HU student constituency and their allies as a liberal non-profit organization giving cover to the war makers and the US ruling class.

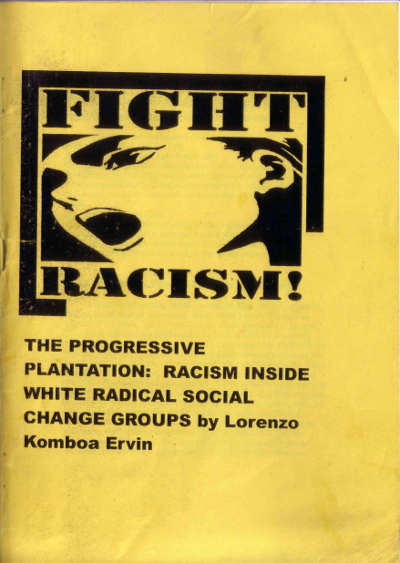

It would be years later upon reading the analysis of leading Black anarchist Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin in his political pamphlet titled The Progressive Plantation: Racism Inside White Radical Social Change Organizations, when I came to fully understand the professor’s limited approach and analysis, which is indicative of both liberals and the Marxist Left. (Coincidentally, I first learned of Kom’boa Ervin via the Amnesty Student Chapter on the University of Maryland campus Spring 2001. While speaking to the group about police brutality in PG County, their Food Not Bombs members exposed me to the case of the Chattanooga 3[4]).

It would be years later upon reading the analysis of leading Black anarchist Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin in his political pamphlet titled The Progressive Plantation: Racism Inside White Radical Social Change Organizations, when I came to fully understand the professor’s limited approach and analysis, which is indicative of both liberals and the Marxist Left. (Coincidentally, I first learned of Kom’boa Ervin via the Amnesty Student Chapter on the University of Maryland campus Spring 2001. While speaking to the group about police brutality in PG County, their Food Not Bombs members exposed me to the case of the Chattanooga 3[4]).

Kom’boa would find common ground with the professor on the futility of anti-oppression training but for different reasons and objectives. The faculty advisor’s focus was not on fighting racism and oppression internally within AI, but to expose class contradictions in the organization with the hopes of siphoning off some youth and students towards his vision of building for a communist world. The professor’s vision was sectarian and not broad based. For Komboa, anti-oppression training is a political fraud, which does absolutely nothing to alleviate the suffering Black staffers and activists endure within the non-profit. Nor does it change the overall character and functioning of the organization itself. In order for a non-profit to become truly anti-oppressive, Kom’boa believes:

It requires an internal anti-racist struggle on the inside of the most serious sort to transform such institutions, so serious that it deals with the very soul and survival of the movement itself. The issue is that if it cannot be saved, then it must be smashed, as it does more harm than good. You cannot put internal racism off to another day, because we create visions of the new society in the type of organizations and movements we build now.[5]

In solidarity with liberals, the professor and his organization outright denied that whites in the United States benefited from any notion of white supremacy and/or white privilege believing that such advocacy was a divisive tool of the ruling class. When challenged to explain the disproportionate lives of Black people in comparison to Whites in the US the Professor referred to it as differential oppression not validating any notion of white privilege. Kom’boa believes the oppression of Black people in the US is dual in nature based upon race-class and that white skin privilege is the ultimate tool of the rulers against a united working class. In Anarchism and The Black Revolution, considered by many to be the definitive statement of Black Anarchism within the United States, Kom’boa states:

In America, hundreds of years ago, the white government and political system were created for the enslavement and exploitation of the labor of Africans, the destruction of the Native people already on the land, and the domination of other peoples of color. It was a colonial regime for white supremacy from inception. Although the capitalists used the system of white skin privilege to great effect to divide the working class of the North, the truth is the capitalists only favored white workers to use them against their own interests, not because there was true “white” class unity. The invention of the “white race” was just a scam to facilitate this exploitation. white workers were bought off to allow their own wage slavery and Africans’ super-exploitation; they struck a deal with the devil, which has hampered all efforts at class unity for the last four centuries or more.[6]

We worked with a broad section of our movement across the region for the upcoming training. One of the ground rules was that participants had to commit for the entire weekend, which disqualified the professor who would only commit to one day. Even so, the professor was adamant on bringing flyers to the training, pushing folks to depart from the planned agenda and leaflet in the streets against the Nazis and Klan. I found this disposition to be preemptively disruptive to the flow of the weekend. I would have found solidarity with the professor if his focus was on fighting racism within the organization itself. Nevertheless, we successfully brought together twenty-two Amnesty members with some staff for the weekend training, which began on a Saturday morning.

The training participants were intergenerational and multi-racial in character encompassing the full breadth of our region. I was elated and felt very proud looking at everyone’s faces as introductions were taking place. Everything seemed to be going pretty well early on until a young white male student from Penn State felt attacked by another participant—a young Black woman from PG County. I recall there was a difference of opinion over the definition of white privilege and the Penn State student taking the difference so personally that he actually departed the training. An older white female AI activist out of PA was adamant in defending the student’s departure believing such training singles out white people for abuse and personal harm. I respected the student’s advocacy within the organization—especially his death penalty abolition work—yet I found his abrupt departure to be premature. I also found the stance of the older white female to be indicative of how racism works within the so-called left by caretaking for the white male who personalizes a position being stated by a Black woman.

One of the highlights of the training was the anti-oppression timeline created by participants noting key dates of victory and setbacks in the struggle for human rights and dignity. I found it sobering and unifying visibly seeing some of the correlations such as the escalation of white fascist terror against Black people in the late 1800’s coinciding with the ruling class attacks against the rise of working-class power exhibited by the Pullman Strike of 1894. The training went on to successful completion however there would be life altering effects in the weeks and months to follow.

Shortly after the training, several staff positions opened within the organization. A deputy director was needed in both the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest regional offices. My interest in both positions varied for different reasons. My advocacy brought me into relationship with the Midwest regional director due to the tragic murder of Timothy Thomas by Cincinnati police in early April 2001, which sparked three days of rebellion in the city. The interest in the Mid-Atlantic was due to it being my home base of operation since my joining the organization.

The major influence upon my decision was my nearly four-year old son Jonathan whom I had recently become the full-time custodial parent of. I wanted to keep him within the DC area where we had built some strong school and community networks. However, applying in the Mid-Atlantic brought deep latent issues to the fore. In retrospect, we had been working within a cold war situation for two years. In my mind, I had a right to apply for the position based on my dedication, production, and work ethic. It was also during the hiring process an internal investigation was launched against me sparked by a recent high school graduate and student leader of an AI Group in PA.

I was accused of having prior knowledge of and condoning a Latino male volunteer for making inappropriate advances in the office during the recent graduate’s time as an intern, which was not true. I didn’t interact with this intern during her internship as she worked in the Legislative wing. In fact, I didn’t even know that the male volunteer and the intern knew each other. It was at the outset of this investigation that I found out the intern’s supporters were the same student who had walked out of the anti-oppression training and the veteran member who supported him under the guise of white people being unfairly targeted by activists of color. This attack on me hit really hard on a personal level. It was clear that this was retaliation for the training and a continuing example of my treatment as a Black man in the organization being that I had never fraternized in the office with staff or interns.

I came away from the hiring process feeling underestimated, undervalued, and marginalized. Despite all of my work over a two- and half-year period, I was not granted a final interview for the position and was told that while being visionary, I lacked essential organizing skills. The newly hired director (former deputy) even offered to help me obtain more training as if that was the real reason I was not given the interview. I internally hit the roof with the double standard approach to accountability within our region and movement. It felt like all the air was literally coming out in terms of my resilience to continue struggling within Amnesty.

After a few days of mulling the decision over, I decided to send a private email to the director outlining my deep disgust with the hiring process along with my view that if I needed more training so did he, especially within the realm of diversification and anti-oppression work. The director’s response to my message was to resign from the staff of Amnesty. He stood firm by his decision not to grant me a final interview, but in doing so he conceded privately that I was the more vital staff member between the two of us. Looking back at it, I believe the director thought his resignation would allow me space to press on but that was not the case. The director failed to understand that his decision not to grant me a final interview was institutional and not personal in nature, that his views on me were the extension of the overall political and social milieu of the organization.

From where I sat in my twenty-five-year-old body, being denied a final interview along with an unjust human resources investigation was the final nail in the coffin for me and so I departed the staff. I was determined to protect my good name and myself from further harm. I called the head of Human Resources and began a negotiation process, which was endorsed by the executive director. It was agreed the investigation would end and that I would resign from the staff with a four-month severance to include my full salary and benefits. In the end, my adversaries were successful in pushing me off the staff, yet I was able to protect myself from further harm, or so I thought at the time. In reality, what happened to me at Amnesty was just the tip of the iceberg and indicative of the environments I would have to survive in no matter where I found myself over the next nearly twenty years.

The late anti-fascist advocate, Paul Robeson, once remarked that the battlefield is everywhere. My experiences within both the non-profit and the military industrial complex has strongly validated both environments as racist and xenophobic to the core, especially in relationship to politically conscious, independent, anti-racist, and autonomous-minded Black men. Interestingly, in contrast to the military, Black men are a rarity within the liberal non-profit world. I found the neoliberal environments to be overly reactionary against my masculinity. The ultra-conservative neo-fascist military embraces masculinity so long as you internalize your own oppression, which is used towards maintaining US imperialism and hegemony both domestically and abroad.[7]

Given all I have seen and experienced, there are lessons from my lived organizing experience that I wish to share with those who have genuine and sincere revolutionary aspirations for the future of our shared humanity.

First, if you’re going to work at a non-profit, do so from the base of an organizing constituency working towards revolutionary change and not as a careerist looking to solely advance individually. The non-profit is nothing less than the de facto extension of the reactionary state and is ultimately accountable to its Board and liberal establishment (i.e. politicians and funders) and not the grassroots directly impacted base it supposedly advocates for. Sadly, even poverty within capitalism is a commodity to be leveraged by political opportunists. Understand and embrace from the outset that at some point you will be attacked by the anti-people within the organization and it may come from all sides (volunteers, interns, staff, board) as my experience with Amnesty taught me twenty years ago. Your ability to survive for a period of time, thereby winning potential adherents to a longer-term alternative trajectory, depends on the strength of your base within the organization both internally and externally. However, allies alone without a serious internal organizing strategy can only go so far.

For liberal non-profit executives and careerists, racial equity does not equate to being anti-racist and anti-oppressive. Kom’boa gives a ten-point prescription from The Progressive Plantation on how antiauthoritarian fighters can potentially transform an organization.[8] Three of these points directly and intimately relate to my personal experience within both the non-profit and military complex.

- Never tolerate racism in any form. This includes racist jokes, harassing POC, covering up racist incidents (no matter how miniscule).

- Never back away or withdraw from a racist group, you have the absolute duty to stay and fight within a racist structure to transform it or smash it in the internal fight over racism. You must organize with others, both white people and POC, and build a powerful caucus that can check the leaders and racist members of the board.

- Do not hire, or allow the group to hire, Black and other POCs just for window dressing in the social change movement, but give them the actual power and room to do their jobs without interference from jealous or racist members of the group. [9] Make sure that they have all the support and backing of the group, and do not have to demean or prostitute themselves to keep a job. Do not allow them to be fired without any support or struggle.

Point number two speaks to why I am critical of my early experience with Amnesty and how I responded to the situation. Instead of just cutting out from the staff in an attempt to save myself from further harm, I should have stayed and fought against the racist investigation. My analysis and experiences at that point were limited and not internalized enough to understand that racism and xenophobia are at the very foundation of nearly every institution within these United States. Had I stayed and fought, allies and supporters could have potentially been consolidated within a longer-term struggle to transform the region (In fact, the professor I spoke of had pushed me to stay on staff though solely for the purpose of building his party and not to fight organizational racism).

By the time I was an enlisted sailor within the Navy three years later with a Hangman’s Noose dangling in my face, I was a bit stronger and understood that racism had to be fought in a direct and uncompromising manner and that I needed to utilize all the organizational tools at my disposal. In that instance, unlike leaving Amnesty, I took action. Upon writing a letter to the entire chain of command, I sparked an equal opportunity investigation, that resulted in nearly a third of my shop, which was highly multi-racial in character (including one white woman who was persistently taunted with sexist jokes and misogyny), indicating that some form of racism and xenophobia existed in our workspace. This led to a modicum of justice and an improved work center for the duration of my tenure on the ship.[10]

When I became a community organizer for Empower DC in my early forties, I had become an uncompromising anti-racist with a deeply internalized worldview on how non-profits can perpetuate oppression within the organization if left unchecked. In solidarity with Komboa’s point number one in The Progressive Plantation—to never tolerate racism of any kind—I challenged the organizing director for jokingly referring to my wife (who he had never even met) as a “maid” who retrieves coffee cups left after a staff meeting. I raised this issue both verbally and in a letter to the executive leadership. This, not surprisingly, was to no avail and I was ultimately fired, one week after a raise and promotion, for my inability to just suck it up and internalize the oppression and overt racism displayed by the Organizing Director which was ultimately supported by the Executive Director and Board.[11]

Ultimately, we must strive to build “dual power,” while working on non-profit staffs. Dual power means that as a staff member you’re leveraging the non-profit to build independent, autonomous organizations from the grassroots that can ultimately challenge the existence of the non-profit itself by harnessing the untapped power of those who are directly impacted. While working on staff for Amnesty, I helped to sustain and build such an organization known as the Prince George’s People’s Coalition. Again, no organization in our society is immune to the internal dynamics of systemic racism, and, in 2001, we challenged both the electoral political structure and the liberals within the coalition by launching a Dirty Dozen campaign against killer cops in the county. Then, twelve years later in the aftermath of the Trayvon Martin verdict, we once more were forced to challenge the liberals by going directly to the streets and not to the politicians who are ultimately in the hip pocket of the Fraternal Order of Police.[12]

However, your biggest challenge in building and maintaining an independent autonomous organization will be the political opportunists that are attracted to it for myriad reasons. These opportunists include electoral political aspirants, non-profit staffers, and sectarians of all stripes—including those from the Marxist (supposed Left), Black nationalist forces and secular groups. Our job as Libertarian Socialists is to draw out and strengthen the most genuine fighters from within these reactionary forces through conflictual and opposing relationships. This will enable the most sincere, antiauthoritarian strugglers to consolidate themselves. And, in so doing, they will move the organization to the next stage of revolutionary development and action. My twenty-five-plus years of consistent commitment to the people’s struggle proves that the struggle is eternal, both external and internal.

As the late Chicago Black Panther Fred Hampton taught us, “Theory is cool, but theory with no practice ain’t shit.”

Pressing Ever Onward. JH

Corrective note from the author

I recently came across an internal communication to a comrade dated April 28, 2003, that indicates my initial account of the Amnesty Mid-Atlantic Anti-Oppression Training in the Summer of 2002 was somewhat off. The white Penn State student activist I had mentioned departing early from the training along with his mentor did not do so after a disagreement with a Black participant over the definition of white privilege. The student had apparently received death threats based on refugee support work, leading him to correctly observe during the training how we all make ourselves more vulnerable when we engage in human rights work. In response to the student’s statement, one of the core anti-oppression trainers, a Latino man and organizer from Project South, stated that while we may all become vulnerable, not everyone is pumped with 41 shots in their back (said about the brutal murder of Guinean immigrant Amadou Diallo by NYC Police in February 1999).

The student activist and his mentor interpreted the trainer’s statement as a personal attack and demanded an apology from him, which he refused to give. In response, the two of them left. In the immediate aftermath, even though I was not involved in the exchange, as the training’s core organizer, the student held me responsible and believed that I should have defended him. I, however, didn’t believe the trainer had attacked the student personally.

Jonathan W. Hutto, Sr., is an anti-oppression community organizer and author who has made substantial contributions within both non-profits and grassroots organizations for over twenty-five years. In 2006, as an enlisted member of the United States Navy, he co-founded the Appeal For Redress from the Iraq War, which was awarded the 2007 Letelier Moffit Human Rights Award from the Institute for Policy Studies. He can be reached at jonathanhutto99@gmail.com

Notes

[1] H Rap Brown. “Untitled” speech, Cambridge, MD. Delivered July 24, 1967. Compiled by Lawrence Peskin and Dawn Almes, Maryland State Archive. Available at: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2200/sc2221/000012/000008/html/speech1.html.

[2] For firsthand accounts and more information on 1990s student activism at Howard University, including my own organizing work, you can search The Hilltop online archive: https://dh.howard.edu/do/search/.

[3] For more on the Peoples’ Institute for Survival and Beyond see: https://pisab.org/.

[4] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin and seven other civil rights protesters were named “The Chattanooga 3″ following their arrest on May 13, 1993, for the Hamilton County Grand Jury’s failure to prosecute eight white law enforcement officers in the murder of a 32-year-old Black man. For more on the Chattanooga 3 see: https://libcom.org/library/support-lorenzo-ervin-chattanooga-three.

[5] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. 2011. The Progressive Plantation: Racism Inside White Radical Social Change Groups, 43-43. Available at: http://libcom.org/library/progressive-plantation-racism-inside-white-radical-social-change-groups.

[6] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. 1979. Anarchism and the Black Revolution: The Definitive Edition. Pluto Press, 79-81.

[7] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. 1979, 79-81.

[8] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. 2011. The Progressive Plantation: Racism Inside White Radical Social Change Groups, 45-46. Available at: http://libcom.org/library/progressive-plantation-racism-inside-white-radical-social-change-groups.

[9] Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. 2011, 45-46.

[10] I spoke about my struggles in the Navy on the podcast, Courage to Resist, February 17, 2021: https://couragetoresist.org/podcast-jonathan-hutto/.

[11] I discussed both my firing and the ongoing Discrimination-Retaliation complaint filed with the DC Office of Human rights with Zakiya Sankara Jabar on her show in May 2021: Real Talk.

[12] I co-authored a paper in 2016 titled “Social Movements Against Racist Police Brutality and Department of Justice Intervention in Prince George’s County Maryland,” which details the Dual Power strategy of the People’s Coalition from the early 2000’s until 2016: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4824689/.

This is awesome JH. Great Read. !!!!

Appreciate you Good Brother-Drew Hall Forever! In the Spirit of Mahmoud, “Maintaining” 🙂 Pressing. JH